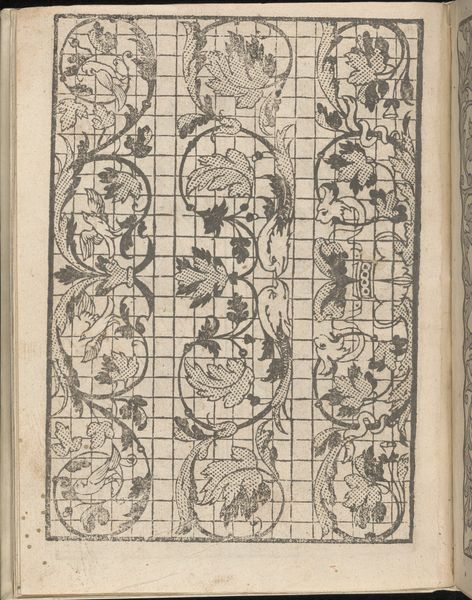

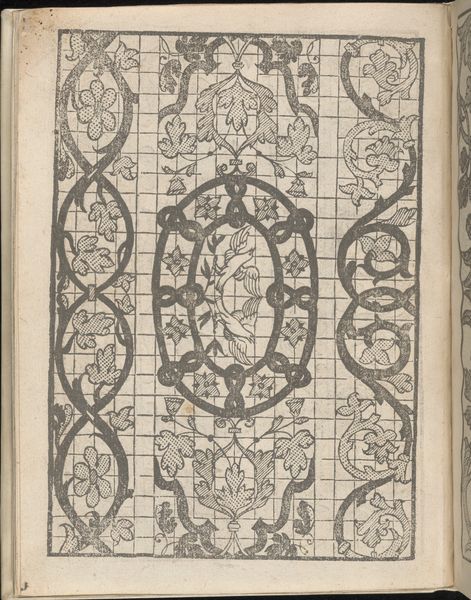

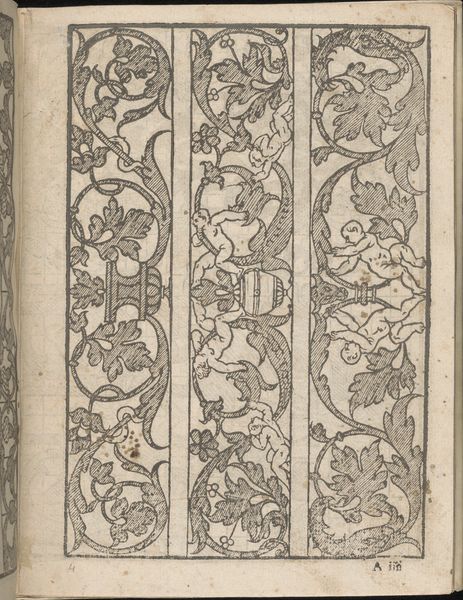

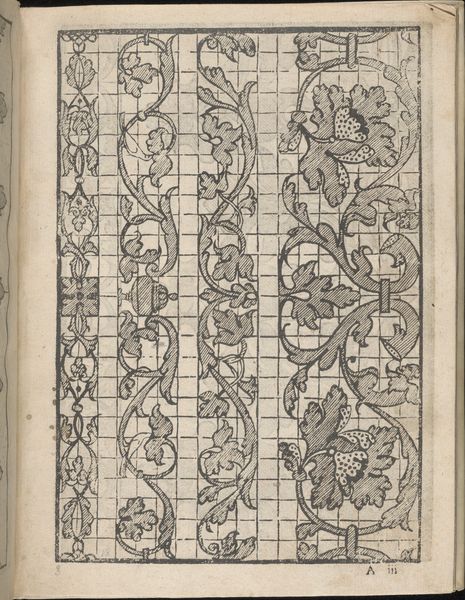

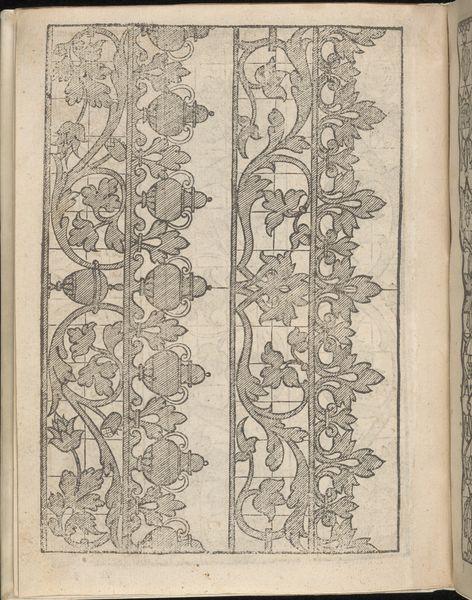

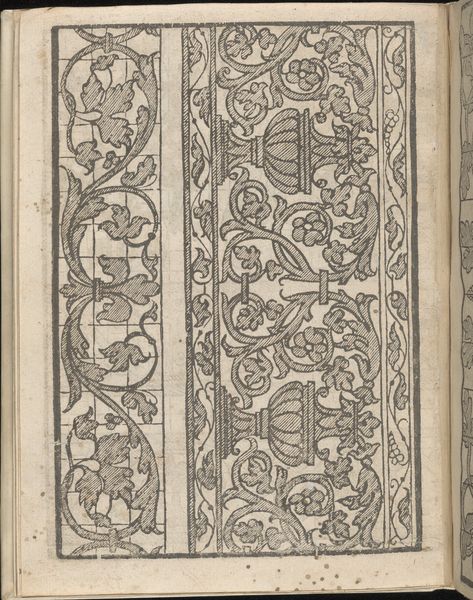

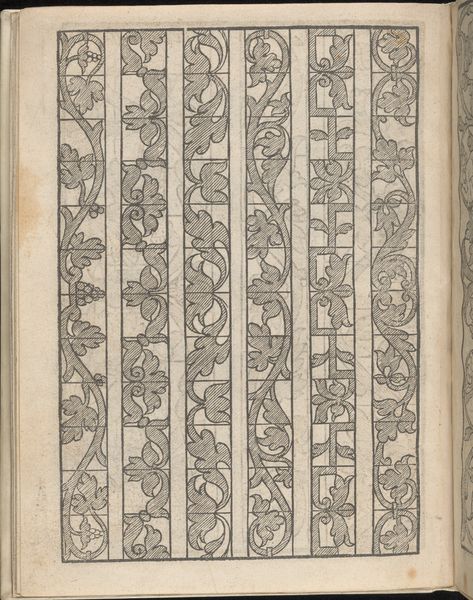

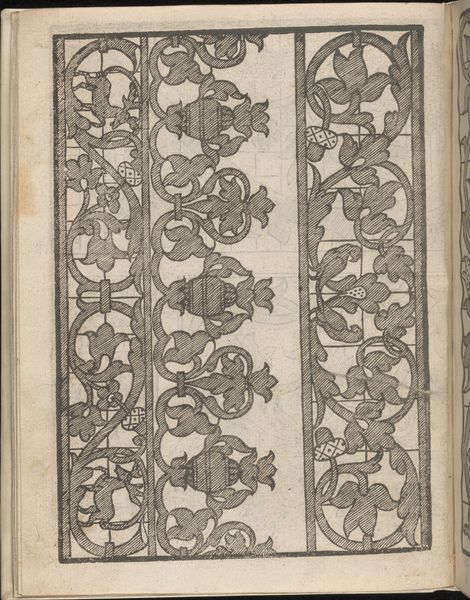

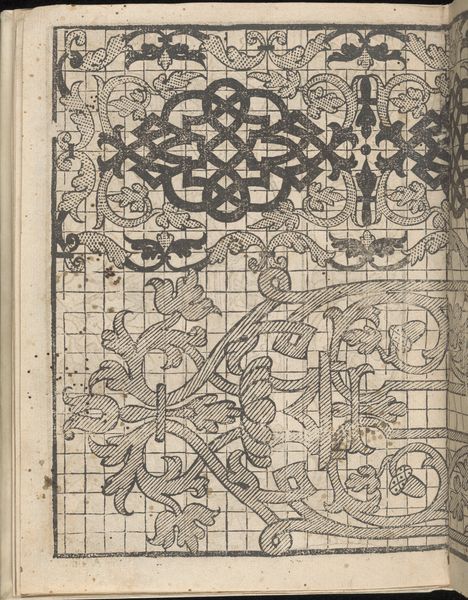

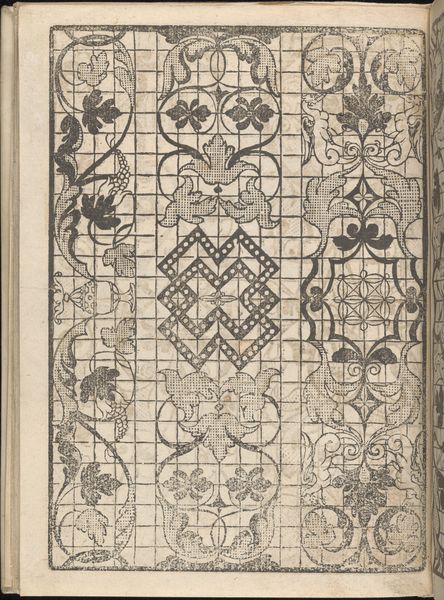

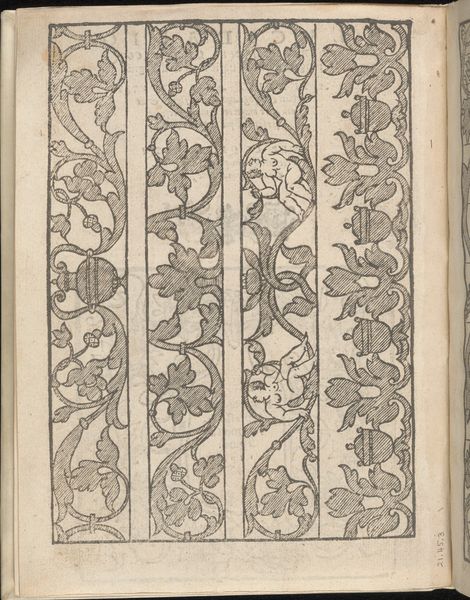

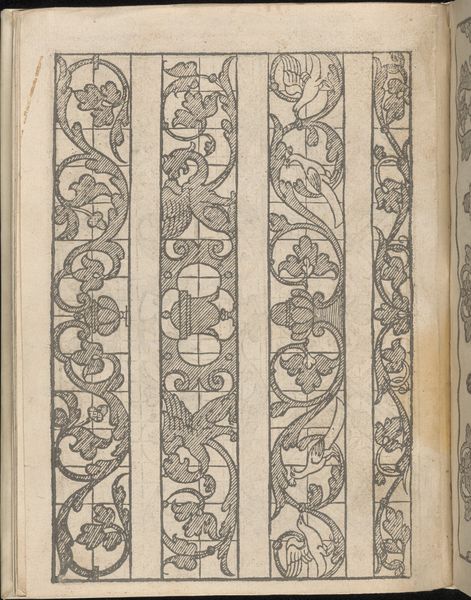

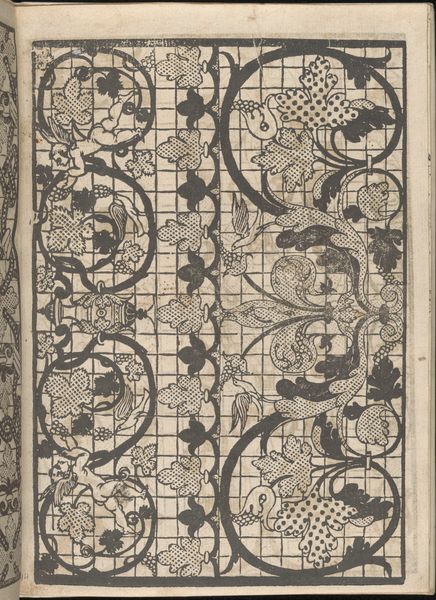

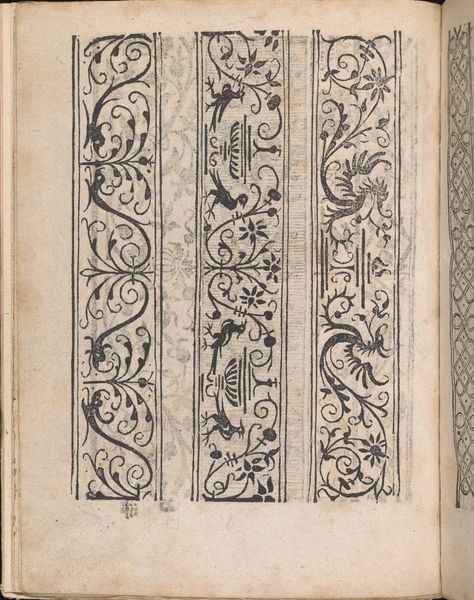

drawing, graphic-art, print, paper, ink, engraving

#

drawing

#

graphic-art

#

medieval

#

pen drawing

#

ink paper printed

# print

#

book

#

paper

#

ink

#

geometric

#

line

#

engraving

Dimensions: Overall: 7 7/8 x 5 7/8 in. (20 x 15 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have a page from Iseppo Foresto’s “Lucidario di Recami,” dated 1564. This particular sheet, executed in pen and ink, is a stunning example of 16th-century Italian pattern design intended for engravings and use by artisans. Editor: The tight, repetitive patterning immediately strikes me. Each vine and leaf seems carefully contained, like a botanical specimen pinned in place. There's a rigidity here that feels quite controlled. Curator: Precisely. These weren’t meant to be artworks in the modern sense but rather functional guides. Artisans, likely women involved in lacemaking and embroidery, would use such manuals to create complex designs for textiles and other decorative arts. The grid behind the forms makes it look modern, like technical drawings from today. Editor: That grid fascinates me. It both constrains the organic forms and provides a structure for limitless variation. How might these patterns have empowered or perhaps even restricted the creative agency of those artisans using them? Was it offering artistic options to working-class people who would not otherwise have had access? Or was it the industrialisation of craft? Curator: It’s a complex relationship, certainly. On one hand, pattern books like this democratized design, making sophisticated motifs accessible beyond the elite. At the same time, the standardization could limit innovation, dictating aesthetic norms, potentially limiting self expression. You should bear in mind also, of course, that there was good money to be made copying, using and reinterpreting patterns – and people's livelihoods depended on the forms being clear. Editor: Thinking about the social context is crucial here. These patterns wouldn't exist without considering a historical lineage of labour – specifically gendered labour in workshops or as a form of domestic employment – creating social order through craft. The book seems both prescriptive and full of possibilities. Curator: Agreed. Seeing the artwork this way truly enriches our appreciation for the complex interplay between design, labour, and social change during the Renaissance. Editor: And by exploring all these constraints – of labour and identity, and how gender played a role at that moment in history. It changes how we look at what we now simply consider to be beautiful decorative shapes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.