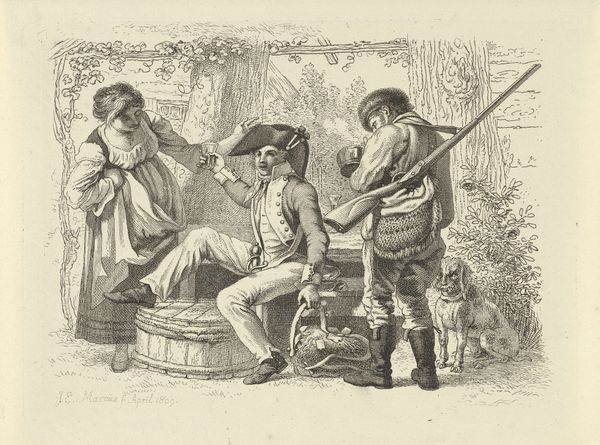

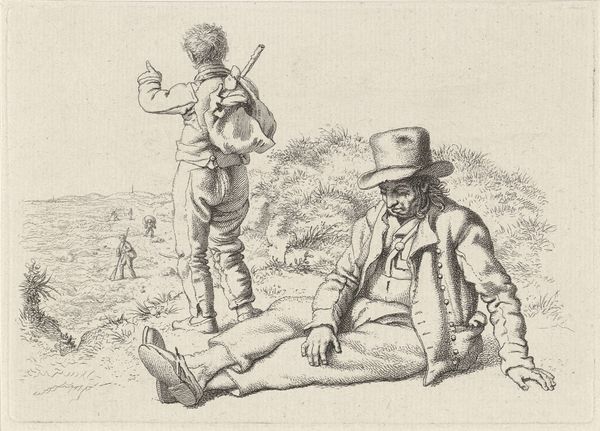

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

romanticism

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 154 mm, width 187 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let's turn our attention to "Standing and a Sitting Hunter" by Jacob Ernst Marcus, a print dating from 1811 to 1817. The piece, executed as an engraving, currently resides here at the Rijksmuseum. What strikes you first about this scene? Editor: There’s a stillness, almost a melancholy to it. The standing figure, leaning against the tree, seems burdened, while the seated hunter possesses an air of weariness. Curator: Indeed. Consider the context. These figures represent a romanticized version of rural life, echoing the artistic movements favoring the ‘noble savage’ and simpler existence, a sentiment that critiqued the burgeoning industrial society. Editor: And yet, who are these figures actually meant to represent? They certainly dress in ways that invoke those colonial narratives about the frontiersmen. This begs the question: what assumptions are being perpetuated about masculinity and its relation to the natural landscape here? Is there violence suggested, even erased, through their presentation as quiet watchers of the land? Curator: That's an excellent point. The romantic ideal often masked the realities of these encounters. Look closely at the details – the rifles, the fur caps – symbols both of survival and dominance, reflecting societal power structures through hunting and connection with land. Their inclusion suggests the very real impact they were having on the environment as a consequence of these power imbalances. Editor: The tension for me is located right there. The picturesque nature scene, a space presumably ‘untouched’ by modernity is contrasted by armed men enacting a very masculine vision. I see a moment of pause that invites us to examine who is given power and how violence to the landscape itself becomes an extension of gendered ideals. Curator: I find it interesting that Marcus chooses engraving for this piece. Engraving allowed for wider distribution of these images, shaping the contemporary understanding and acceptance of these scenes. This method of image sharing democratized access and reinforced cultural values and their problematic roots in real-time. Editor: Precisely. We can observe these supposedly quiet images as powerful forms of communication about what activities and relationships with nature are promoted, and what they omit, as they circulate through different viewing contexts and time. Curator: It really does push us to confront how we visualize history, especially these romantic depictions that have socio-political dimensions with lingering effects. Editor: Definitely gives you pause for thought, doesn't it? A picture, literally, telling a thousand not-so-simple words.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.