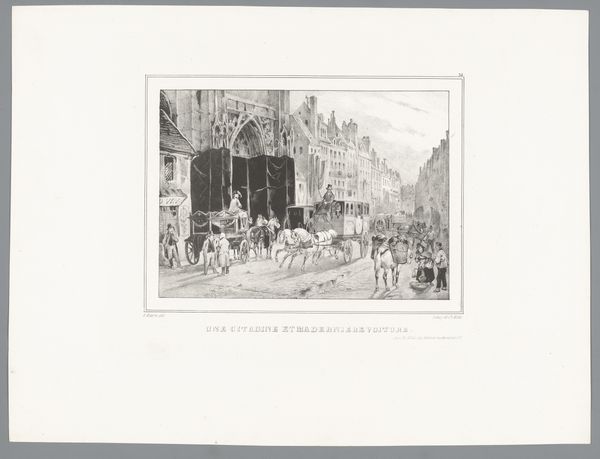

print, etching

# print

#

etching

#

romanticism

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 235 mm, width 305 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here at the Rijksmuseum, we're looking at "Gevechten in de Schaarbeekstraat in Brussel" by Paulus Lauters, created sometime between 1830 and 1831. It's an etching, printed on paper. What's your initial reaction to this cityscape, Editor? Editor: Chaos, but organized. There's a real sense of tension, but also a strange formality in the figures. It feels like a historical painting attempting to capture something far more immediate and disruptive. Curator: Disruptive is a great word here. Look at the use of light and shadow; how Lauters uses contrast to draw our eyes to the active combat in the street’s center. It emphasizes the drama through visual means. Editor: Absolutely, but the context is essential. This work depicts fighting in Brussels during the Belgian Revolution. Knowing that, those rigidly posed figures take on a different meaning. They aren't just arranged for pictorial balance; they represent very specific participants in a fight for independence, for national identity. The smoke is not just aesthetic; it is a mark of a nation being born through violent struggle. Curator: And yet, consider the architecture itself. The etching presents a seemingly orderly street, bisected by perspective, creating depth through architectural forms. It is an example of structure underlying turmoil. Editor: Yes, but the architecture also tells us something about class. Whose buildings are these? Who benefits from the established order, and who is fighting to overturn it? What’s being etched here is a social upheaval – a violent remaking of power in urban space. Look, many figures are actively looking outward toward the viewer, breaking the 4th wall; their revolution demands witnesses. Curator: A clever insight, placing the viewer at the forefront. However, the print medium also invites scrutiny: its very reproduction speaks to a wider distribution of revolutionary ideals. Editor: Precisely. An etching like this becomes a form of propaganda, a call to action distributed through the very networks it depicts being fought over. This is where art meets social change in the streets of Brussels. Curator: A compelling argument. I still find myself drawn to the formal composition, but seeing it as part of that revolutionary context undeniably enriches the reading. Editor: It reminds us that form isn't divorced from content; it's often deeply entwined with the historical and political forces that shape art and our experience of the world.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.