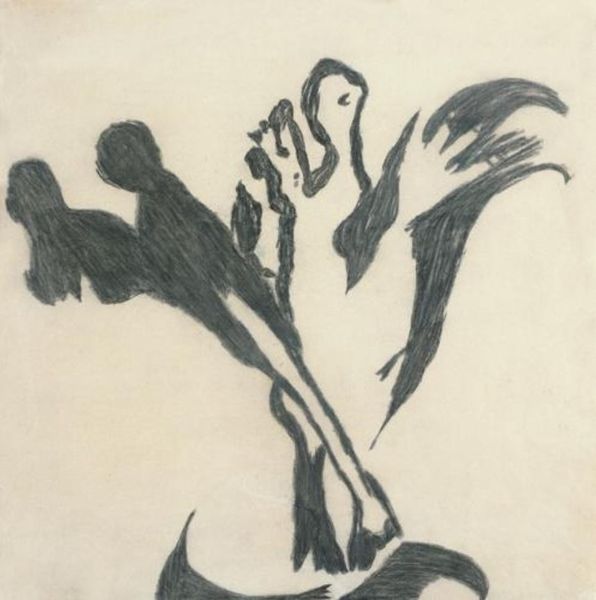

Copyright: Oleg Holosiy,Fair Use

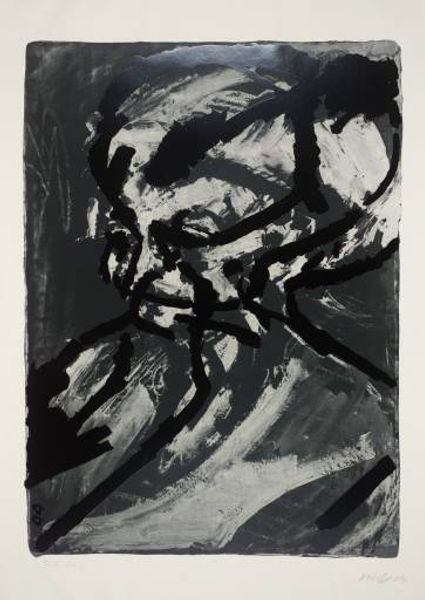

Curator: Here we have Oleg Holosiy’s "Profile with Cherubs," an oil painting from 1991. The work immediately strikes me with its haunting mood. What’s your first take? Editor: My initial impression is the rawness. You can practically feel the viscosity of the oil paint. Notice the heavy brushstrokes, the visible layers revealing a strenuous creation process. It evokes a feeling of intense labor and urgency. Curator: Indeed. The cherubs especially. Though seemingly classical symbols of innocence, their aggressive application gives them an almost demonic quality. They appear like psychological projections rather than heavenly beings, perhaps symbolizing conflicting aspects of the depicted profile’s psyche. Editor: Precisely. The materiality further reinforces this reading. The use of oil paint, typically associated with traditional, often idealized portraiture, is subverted here. Holosiy abandons polished surfaces, revealing the messy, labored reality of creation. The brown backdrop itself gives the image a heavy atmosphere of labour and artistic actions. Curator: Look at how Holosiy reframes the cherubic iconography. Throughout art history, cherubs represent divine love and heavenly grace. Here, however, their distorted forms, combined with the somber portrait, might suggest repressed desires or the burden of self-awareness. The artist has reworked their semiotic functions entirely. Editor: Absolutely. It begs the question: how did access to materials shape Holosiy's approach? Was it about affordability or making deliberate choices? Neo-Expressionist pieces like this often question the elitism associated with art production and its institutions, revealing the economics involved. Curator: The rough impasto application is typical of Neo-Expressionism. But, by 1991, the movement was essentially considered "dead". Is Holosiy revisiting the symbolic language of early 1980s expressionism with late 20th-century themes? I keep seeing this oscillation between torment and a clumsy type of cherubic "salvation". Editor: A relevant question, and it speaks to broader social circumstances affecting artistic agency. By questioning how art gets created, we simultaneously acknowledge Holosiy’s agency and that of the materials. What sort of patronage supported an expressionist work, against the flow of that moment? Curator: In the end, perhaps Holosiy is revealing something timeless in this juxtaposition of form and content – that the search for inner peace is inherently fraught and messy. Editor: A great point. And through his chosen media, he renders this search strikingly present, reminding us that material reality informs even the most ethereal symbolism.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.