print, woodblock-print

#

portrait

# print

#

asian-art

#

ukiyo-e

#

figuration

#

woodblock-print

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: 10 7/8 x 8 in. (27.6 x 20.3 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

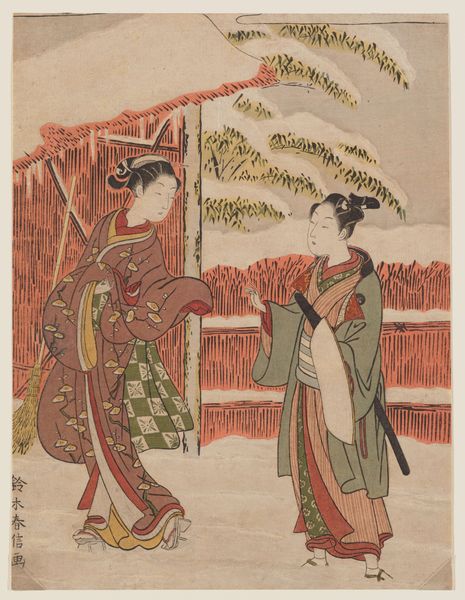

Editor: So, this woodblock print is called "Yozei no In," created sometime between 1756 and 1776 by Suzuki Harunobu. It's currently hanging in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. What strikes me most is the very deliberate, almost architectural construction of the image, with the ladder and building facade dominating the composition. What can you tell me about it? Curator: For me, the power of this work lies in its commentary on material culture. Consider the very act of producing a full-color woodblock print during this period. It was labor-intensive, requiring skilled artisans and specialized materials, thus suggesting the rising prosperity and consumer culture of Edo period Japan, while, by depicting fashionable women enjoying leisure, what societal strata did this representation reinforce or challenge? Editor: I see what you mean. It wasn't just about creating a pretty picture, it was a whole industry! The availability of color and the resources needed to make this print suggests economic and social changes beyond just the artwork itself. Does the poem inscribed atop add another layer? Curator: Absolutely! The inclusion of poetry intertwines textual meaning with the visual narrative, potentially hinting at societal values related to beauty or desire or… Perhaps critiquing a disconnect between lived labor and material display, using artifice to hint that production might be disconnected with access and utility? What if Harunobu uses that cultural allusion as material for comment about production, distribution, labor, and the elite as well? Editor: That's a fascinating point. It makes you think about who this print was made for, and what kind of lifestyle it reflected, or even sold. I initially saw a peaceful genre scene, but you've opened my eyes to how the materials and process embedded a broader commentary on Edo society. Curator: Exactly! By paying close attention to these material details, we can uncover stories far beyond what’s immediately visible. A beautiful reminder that every artwork reflects the cultural and material conditions of its making and consumption.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.