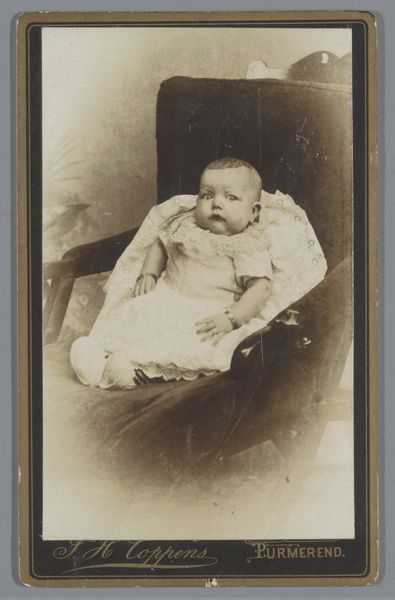

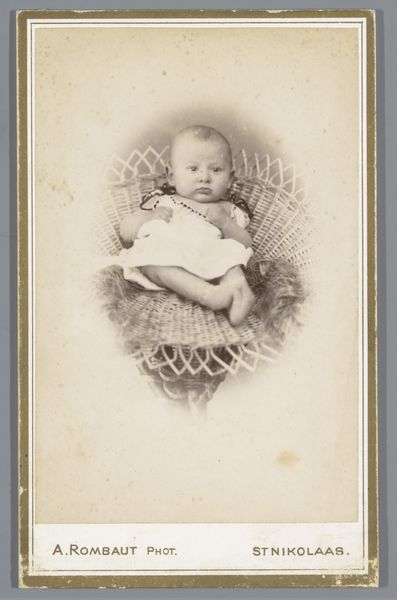

Dimensions: height 103 mm, width 63 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

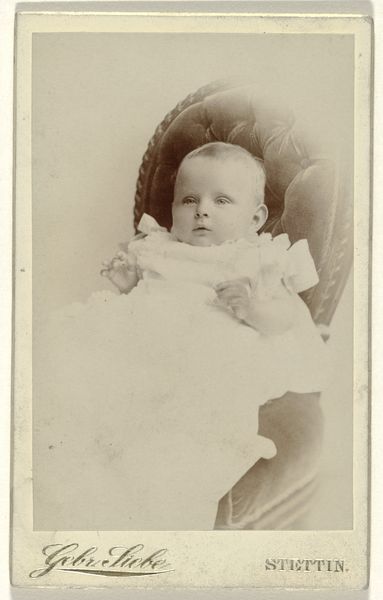

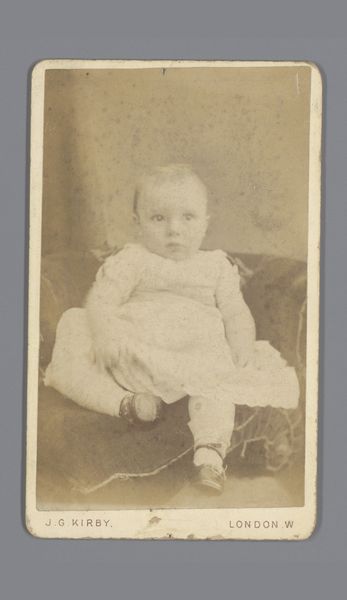

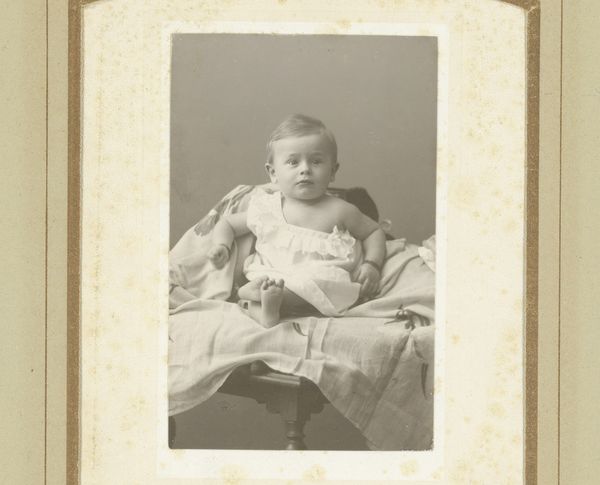

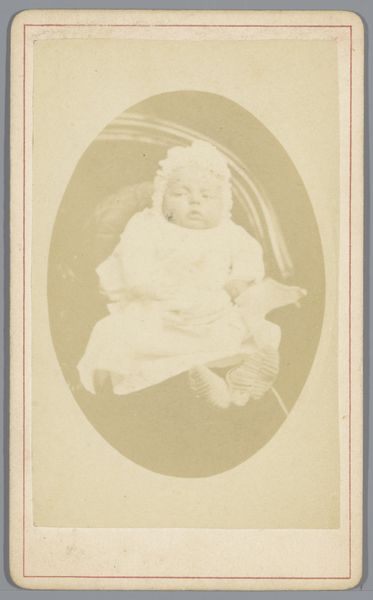

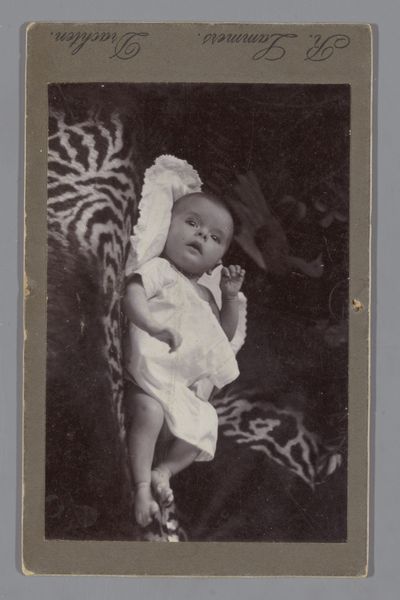

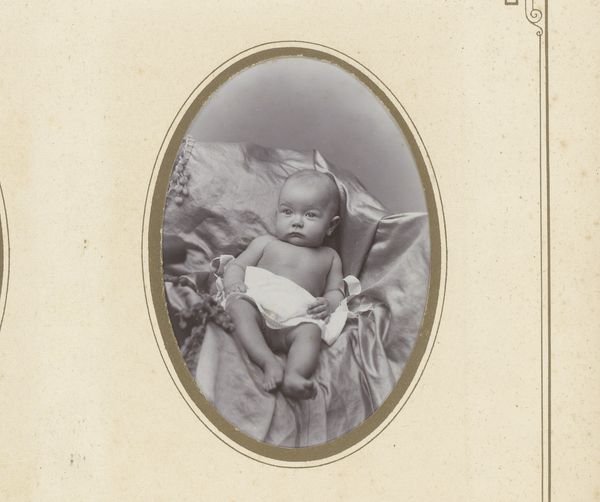

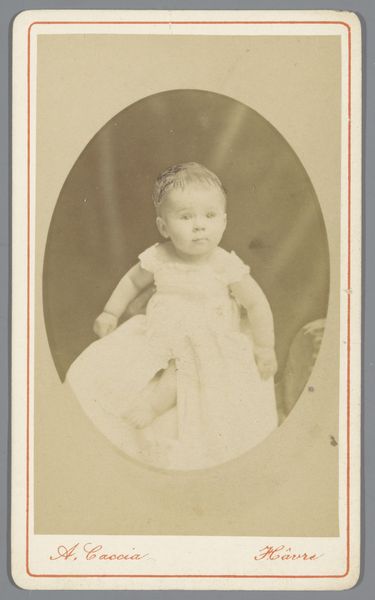

Editor: This gelatin silver print, "Post-mortem portrait of an unknown baby" created between 1900 and 1914 by A. Vannier, is rather unsettling. It feels staged, and there’s a sadness that permeates the image. What do you see in this piece? Curator: The overwhelming weight I sense is that of cultural memory. Consider the cultural context of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Infant mortality was unfortunately common. These post-mortem photographs, while jarring to our contemporary sensibilities, were often the only lasting image a family would have of their child. Editor: So, this was a way to preserve a memory? Almost like a religious icon in a way? Curator: Precisely. Note the stylistic echoes of Romanticism, with its emphasis on emotion and idealization. The carefully arranged setting, the baby's attire… these details transform a moment of grief into a symbolic representation. Do you see how the visual language attempts to transcend the immediate pain of loss? The toys, even faded, become emblems of innocence and potential, suspended in time. It echoes a continuity of love against the stark finality of death. Editor: That makes sense. I was focusing on the morbidity, but you’re highlighting how this image served as a cultural anchor. A symbol of remembrance. Curator: Indeed. These photographs carry an emotional and cultural weight that continues to resonate. Understanding the symbols and the context allows us to engage with the human experience embedded within them. What is your impression now, having looked through this iconographic lens? Editor: I appreciate it more. It’s not just a photograph of death, it is also very much about preserving life and memory, even if in a painful form. Thank you! Curator: My pleasure. Examining the symbols of our past can often clarify how we grapple with universal themes even today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.