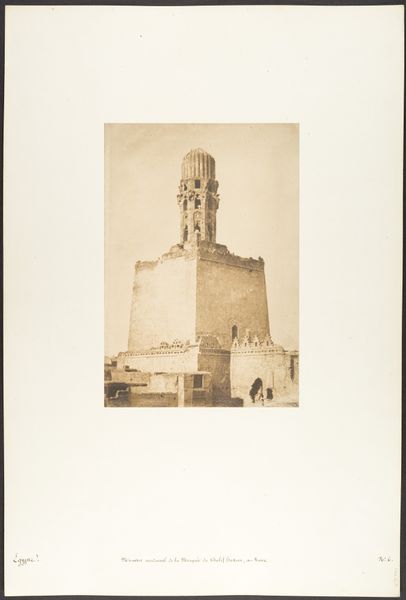

Minaret penché de la Mosquée de Bibars, au Kaire 1849 - 1850

0:00

0:00

photography, architecture

#

landscape

#

photography

#

islamic-art

#

architecture

Dimensions: Image: 8 15/16 × 6 1/4 in. (22.7 × 15.8 cm) Mount: 12 5/16 × 18 11/16 in. (31.2 × 47.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

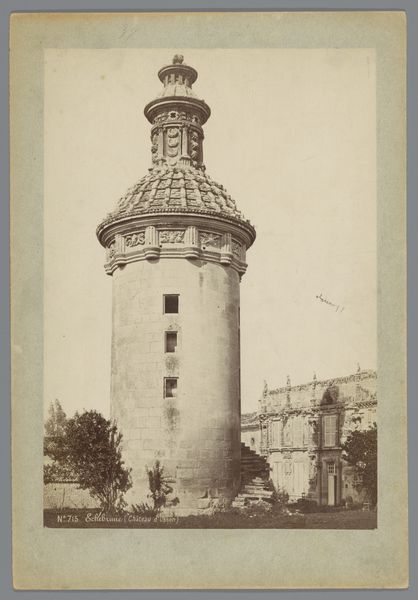

Curator: Let's consider Maxime Du Camp's photographic print from 1849-1850, "Minaret penché de la Mosquée de Bibars, au Kaire," housed here at the Met. What strikes you first about this sepia toned image? Editor: There's a fragility here, an almost mournful quality in how the light reveals the decaying masonry. It's a testament to time and possibly some harder realities too. It’s imperfect, like life. Curator: Indeed. Du Camp was documenting Egypt in a time of immense colonial pressures. The image reveals not just architectural detail but also speaks to labor and the political forces impacting the built environment. Notice how he positions the minaret itself—a slightly off-kilter stance adding to that sense of vulnerability. Editor: Right, because while we see this almost romantic ruin, it's essential to consider what the making of this image involved, the materiality. The photographic process itself—the chemicals, the paper, the social structure that enabled Du Camp to even be there. Those glass plate negatives were fragile cargo! And look at the composition: the damage feels less accidental when considering it within that context. Curator: Exactly, it transcends a mere visual record, doesn’t it? I almost imagine being present in the square as he makes this photograph—a quiet sense of reverence washing over me at the site of ruin. What lingers after seeing such dedication? Editor: A renewed awareness, certainly, a consideration that art extends beyond creative gestures, and bleeds into political landscapes. Every element, from Du Camp's choice of vantage to the paper this thing's printed on reflects production. It's material culture telling a potent story about history and craftsmanship! Curator: For me, Du Camp’s capture of light, almost dreamlike in the aged print, whispers stories of time's passage, its gentle touch—and its less-gentle acts upon monuments. Thank you, this exercise was truly enlightening! Editor: The dialogue allowed for considering aspects of production to become visible. The magic fades when light exposes how much intention and labor went into creating these pieces.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.