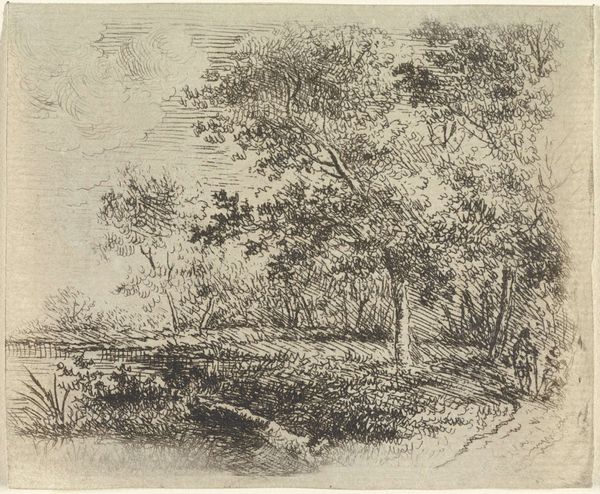

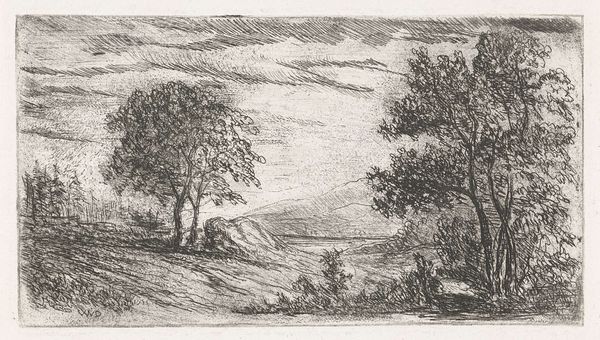

drawing, etching, ink

#

drawing

#

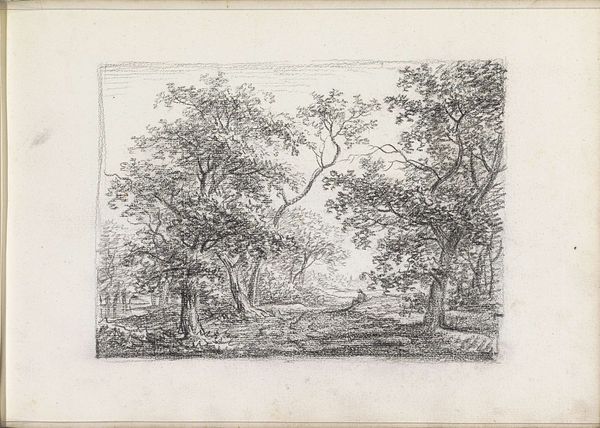

light pencil work

#

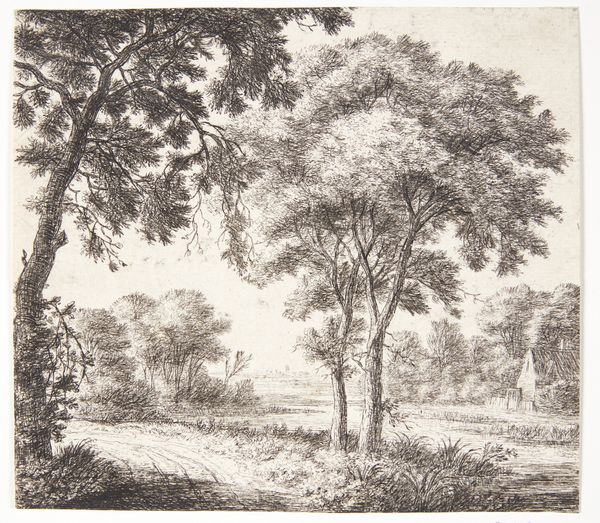

pen drawing

#

pen sketch

#

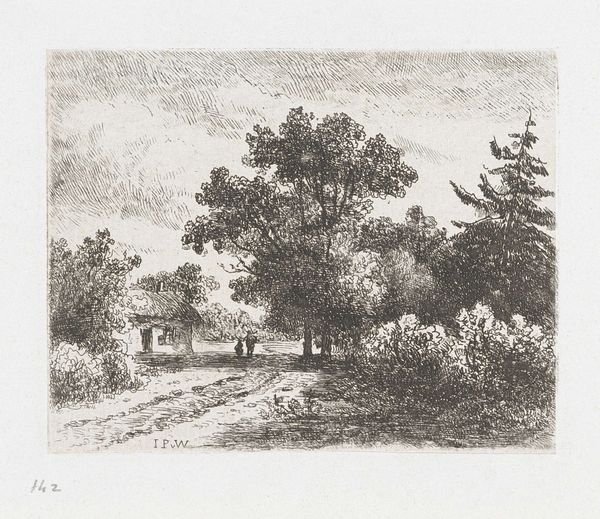

etching

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

sketchbook art

Dimensions: height 74 mm, width 86 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Adrianus van Everdingen’s “Landschap met wilgen,” dating from sometime between 1842 and 1888. It's rendered in ink, likely using an etching technique. Editor: My first impression is one of intimacy, despite the grand subject matter of a landscape. The tight, interwoven lines create a certain depth, but it feels contained, almost secretive. Curator: Well, consider the willow. In many cultures, they symbolize mourning, loss, but also resilience, new beginnings from sorrow. They occupy this almost paradoxical space in the collective imagination. Editor: Paradox is key, I think. Look how much ink is used here. It looks like Van Everdingen really worked and reworked the metal plate to achieve these layered, dense clusters of lines. Did he use soft ground etching combined with drypoint to build this image? Curator: Likely so! The technique becomes integral to the expression. Think of how etching, as a process, echoes the landscape itself. It's subtractive but ultimately additive, eroding the plate, building up the image in darkness. Is the work almost meditative, in a way? Editor: In a material sense, absolutely. The resist had to be applied, lines etched, and then re-etched to vary their depth. Each stage carries weight, influencing the final outcome. There are many possibilities, and his decisions carry through the centuries. Curator: Yes, there’s the personal weight of memory inscribed in those marks, but also a deeper current—of human interaction with nature. The willow is more than a tree. It embodies a story of grief, transformation, a quiet insistence of life even in the face of adversity. Editor: Right. The availability and the relative affordability of the tools, the development of inks, etching plates, and printing presses, they all played their part, expanding printmaking in the nineteenth century. Did the industrialization of agriculture play any part, like a contrast to what it replaced? Curator: Absolutely. These artworks offered views into nature that were slowly vanishing and a window into the soul. It offers a compelling perspective on a time of huge transitions in European life. Editor: I will remember this little meditation on time and change! Curator: An exquisite glimpse into both loss and enduring strength, materialized through a meticulous craft.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.