Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

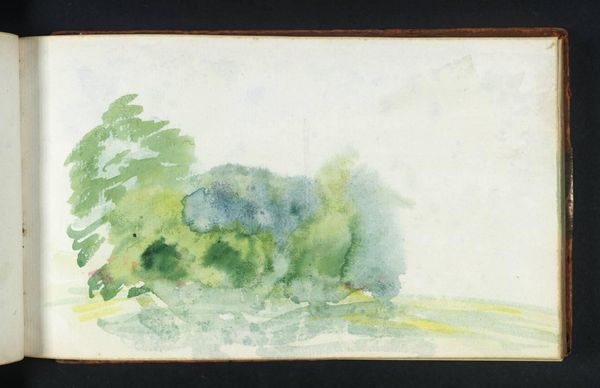

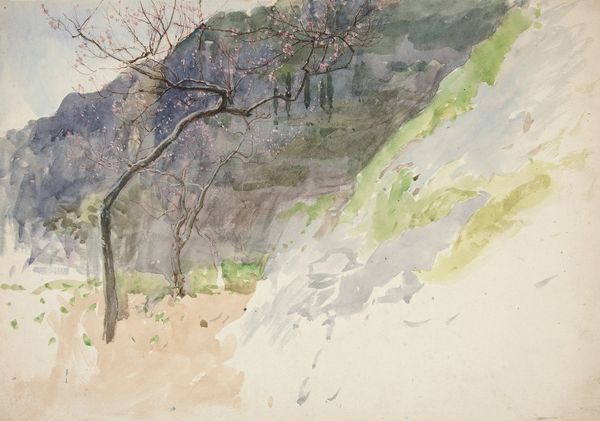

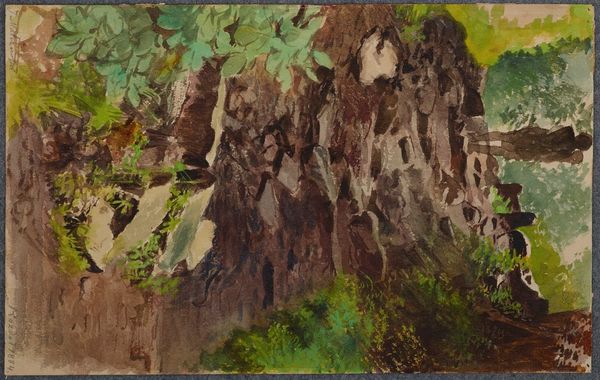

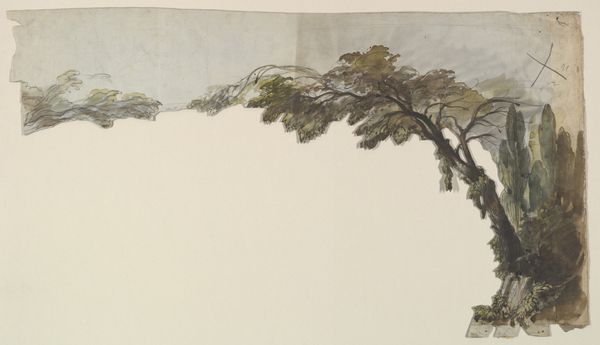

Curator: "Berglandschap met water bij Glion," or "Mountain Landscape with Water near Glion," a watercolor from Anna Catharina Maria van Eeghen, likely created between 1888 and 1901. What are your first impressions? Editor: A very understated scene, wouldn't you say? Muted greens and blues. It makes me think about the physicality of watercolor and how effortlessly she seems to manipulate the watery medium on paper. Curator: Van Eeghen moved within artistic circles that championed 'plein-air' painting. How might painting outdoors have influenced the way she represented the landscape? Editor: Being on-site is pivotal to my understanding of the piece. Note the speed and economy of the marks! She uses quick brushstrokes to capture the light reflecting off the water and the textures of the rocks and foliage, embracing its fleeting nature. Watercolor must have presented some real challenges when dealing with environmental conditions on site. Curator: I agree, there's a freshness that can only come from direct observation, wouldn't you say? Landscapes during the Impressionist period also played an interesting role in the burgeoning tourism industry and growing middle class. Editor: Tourism! That’s a thought, yes. Maybe that partly explains why a work like this could emerge at that particular time? The democratizing potential of watercolors also appeals; portable, readily available materials meant landscape painting didn't necessarily need to be an elitist pursuit. Curator: Very insightful! While artists certainly had a variety of motivations, these works still played a role in constructing perceptions of particular places and lifestyles. It makes you think of the art market itself— who was buying these paintings, and how they were being used or displayed? Editor: That’s an angle I had not previously considered, although you're making me think a great deal about class and artistic production. Looking again at the quick brushwork I feel there is a kind of labor encoded in that handling of materials; maybe there are elements of production here that suggest it was for the artist’s use, and not consumption per se. Curator: True. By investigating paintings like Van Eeghen’s, we start to understand how the role of art history can inform what was valued, why, and who had the power to define artistic importance. Editor: Well, my emphasis would always be on how its made and whether its materials have influenced my viewing of it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.