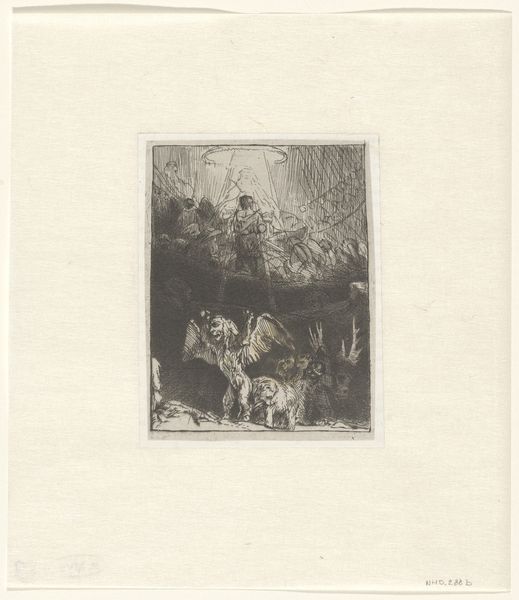

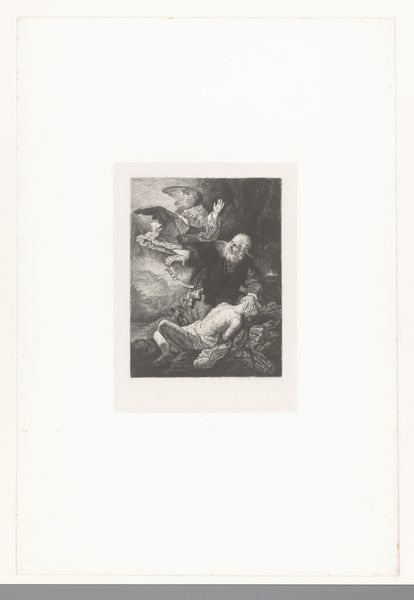

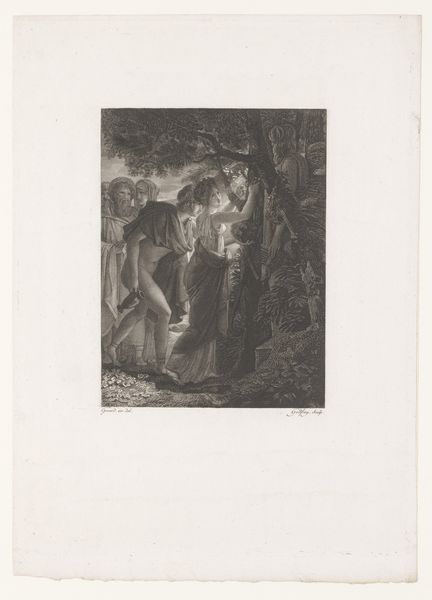

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 111 mm, width 83 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

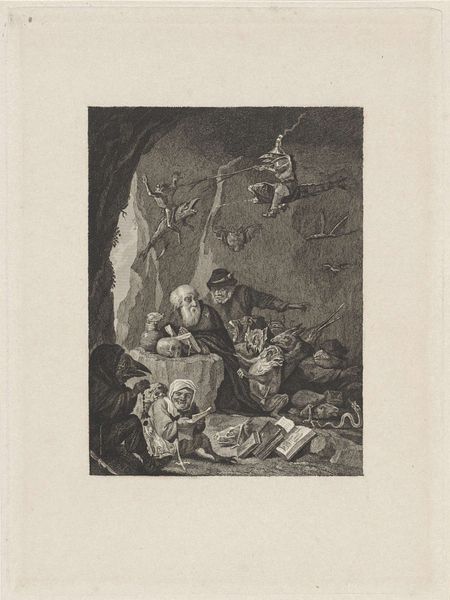

Curator: Here we have "The Agony in the Garden," an engraving dating to after 1651. While the artist is anonymous, the print itself is quite compelling. My initial reaction is one of deep shadow and implied torment; the dense crosshatching creates a somber, almost claustrophobic atmosphere. Editor: Agreed. The gloom is almost palpable. Let's consider the context. The piece portrays Jesus in Gethsemane, wrestling with his fate, as his disciples sleep nearby. This resonates powerfully, especially viewed through a lens of societal struggles against oppression. Think of its depiction of isolated suffering amidst the indifference of the collective, and its historical ties with labor-intensive methods of engraving. Curator: Precisely. The use of engraving as the printmaking technique here is significant. Its intensive labor resonates with ideas of social inequality in creative industries. What appears as a spontaneous or divinely inspired image has passed through skilled manual work. The matrix, as it were, involved someone producing it. Editor: The figures also present certain visual dynamics within that historical lens. Jesus is obviously meant to command our sympathy but are the other men sleeping? Do they choose to look the other way? And that angel that comforts Jesus-- what does it say that that source of solace, perhaps “divine intervention," is something that may have never been afforded in the lives of everyday, and especially disenfranchised people? Curator: Very good points. If we examine it in relation to Dutch printmaking of the era, prints were often affordable ways to disseminate information and moral stories. The texture and line variation achieved through engraving allowed for a certain level of nuance and detail to produce a narrative that could then spread, affecting and shaping a population. Editor: Ultimately, I appreciate how this unassuming engraving, created using demanding labor, can spur us to reflect on our own societies, histories, and systems that lead to both profound isolation and to what exactly becomes someone’s "garden" in times of suffering. Curator: A final reflection; I’d say that this careful manipulation of material – the copper, the ink – creates an image designed for mass production and distribution. It transcends mere decoration, but a conscious effort of cultural creation through technique, texture, labor, and access.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.