photography

#

portrait

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

16_19th-century

#

photo restoration

#

parchment

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

old-timey

#

19th century

#

warm-toned

#

genre-painting

#

golden font

#

realism

#

historical font

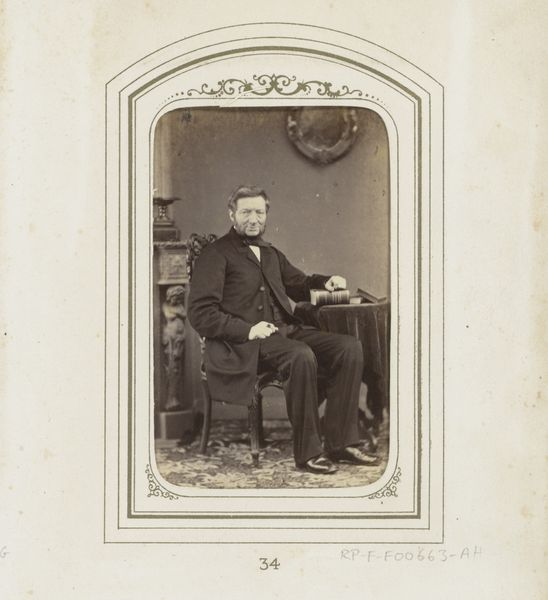

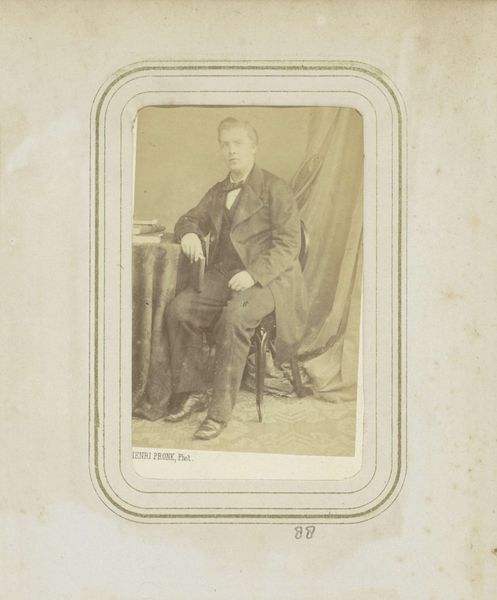

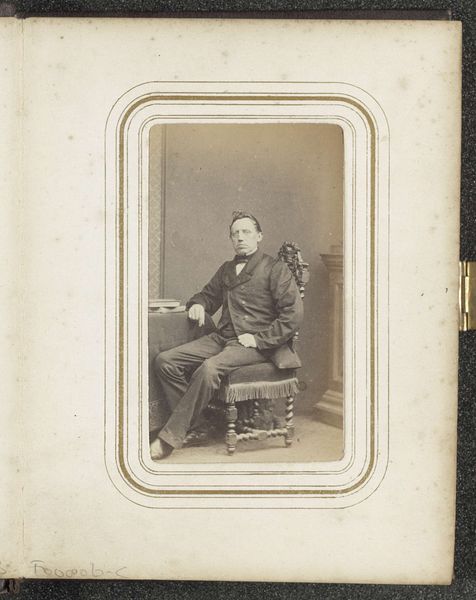

Dimensions: height 82 mm, width 52 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

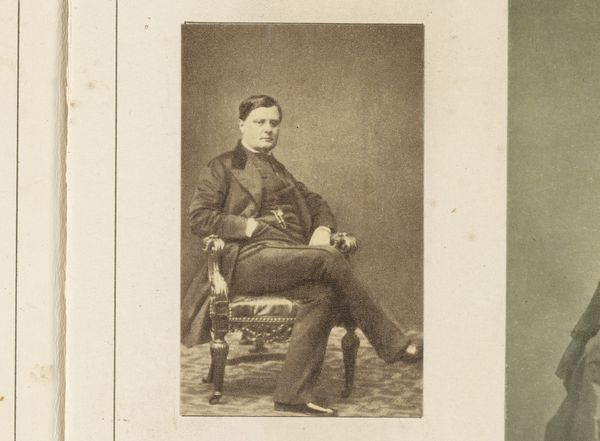

Editor: Here we have what’s known as “Portret van een zittende man met wandelstok in de hand”, a photographic portrait by Alphonse Le Blondel, sometime between 1850 and 1875. It gives off such a formal and almost austere feeling. How would you interpret this work, keeping in mind the time it was made? Curator: This portrait is a fascinating window into the mid-19th century, a period of profound social and technological change. Photography was relatively new and primarily available to the upper and middle classes. What message does that send? Editor: It suggests photography was a status symbol. The subject clearly had the means to commission this portrait. Was this how the upper class saw itself, and wished to be seen? Curator: Precisely! The man’s formal attire, his upright posture, and the inclusion of a walking stick—these all convey an image of respectability, authority, and affluence. Photography was rapidly transforming the relationship between social class, personal identity and public image. Consider how painted portraits before that time period were largely restricted to royalty and high-ranking nobles. The proliferation of photography enabled a wider scope of individuals to be able to project and disseminate the image of power to the outside world. What effect would that ultimately have on society? Editor: It would democratize portraiture to some extent, allowing more people to participate in image-making, or at least image projection. Thank you. It’s been really enlightening to think about this image in its social and historical context. Curator: My pleasure. Considering how the very act of image-making can be inherently intertwined with politics, social statements and power dynamics adds so much more depth to what otherwise might seem like a quaint, historical picture.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.