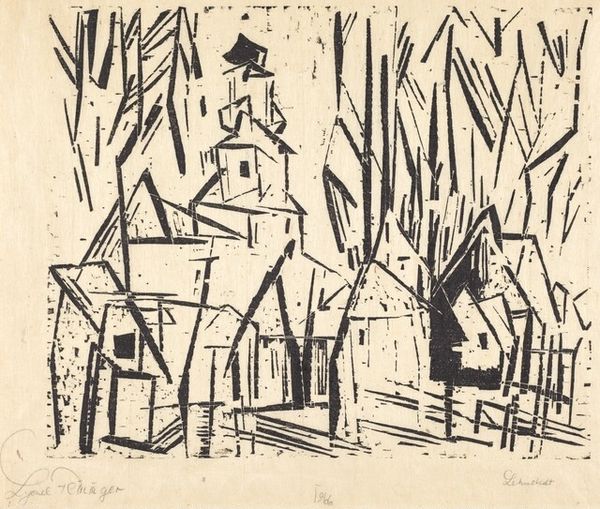

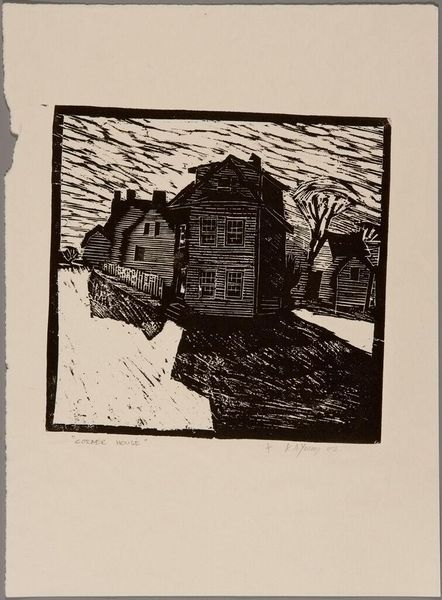

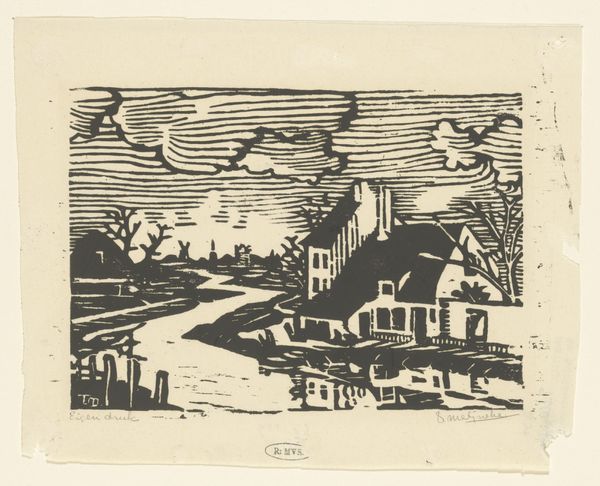

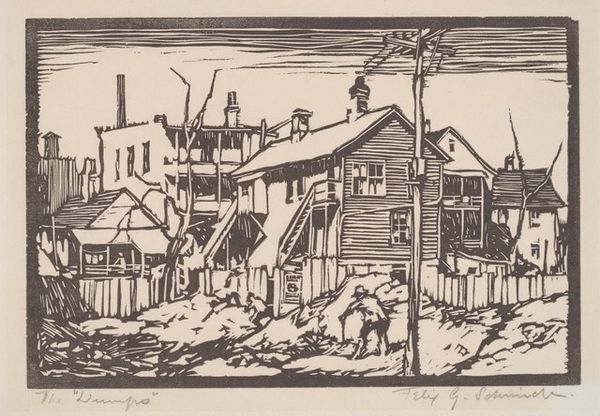

print, woodcut

# print

#

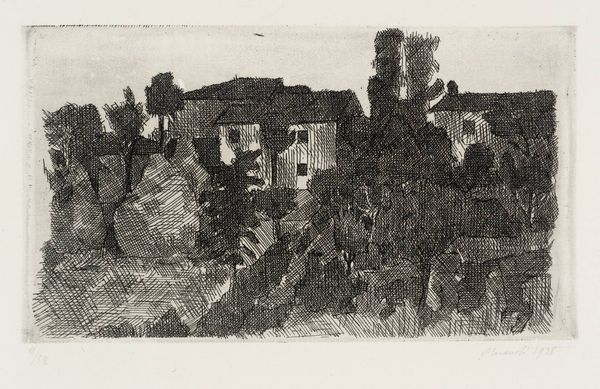

landscape

#

german-expressionism

#

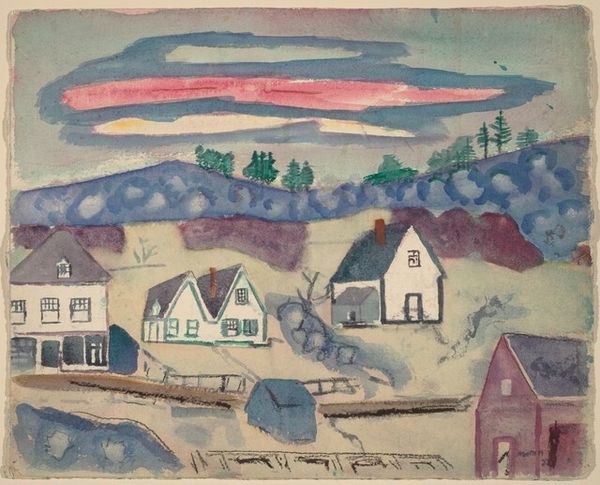

linocut print

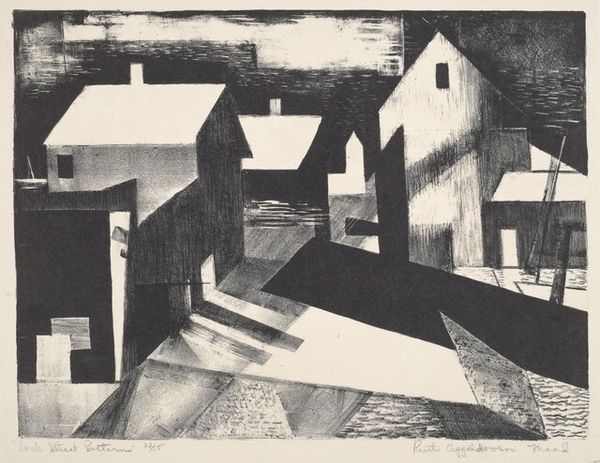

#

geometric

#

woodcut

#

cityscape

Dimensions: image (irregular): 8.1 × 11.43 cm (3 3/16 × 4 1/2 in.) sheet: 11.75 × 19.05 cm (4 5/8 × 7 1/2 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Before us is Lyonel Feininger's woodcut titled "Church and Village," created around 1910. Editor: Immediately, I'm struck by its austerity. The harsh black lines against the peach background—it feels stark, almost a critique. Curator: Absolutely. The starkness underscores the primitive and spiritual yearnings common in Expressionist art. The church, centered but not dominant, becomes an anchor, its steeple a symbolic conduit to the divine. Notice the angular geometry. Editor: That geometry, for me, speaks to the fracturing of traditional social structures at the time. Look how the houses seem crowded, almost menacing in their uniformity. This isn't a celebration of idyllic village life; it feels more like an interrogation of it. It reflects social anxiety. Curator: I see your point. But, focusing on the spiritual, the repetition of shapes—the triangles of the roofs, the rectangles of the houses—creates a rhythm, a visual mantra. Feininger, influenced by Cubism, used these fragmented forms not just to reflect chaos but to uncover hidden orders. It almost embodies medieval cityscapes rendered in modernist styles. Editor: True, that tension is what makes it so compelling. He’s holding onto some semblance of tradition—the church, the village—while simultaneously deconstructing it. And for whom? It reminds me of Walter Benjamin’s essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction," posing questions of authenticity and cultural capital during an age of enormous disruption, like industrialization. Curator: I hadn't considered Benjamin, that's a valuable approach. To move slightly to visual symbolism: The black and white contrast could echo the moral certainties of that era, sharply divided but challenged by new ideologies. Editor: And perhaps by Feininger's own artistic explorations? It certainly invites us to question what we perceive as stable or permanent. Curator: I agree. I walk away pondering how such seemingly simple visual constructs—shapes, lines—carry such heavy emotional and cultural meaning. Editor: For me, it's how art engages in the political; through visual deconstruction it lays bare how those rigid systems ultimately create their own unique forms of imprisonment.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.