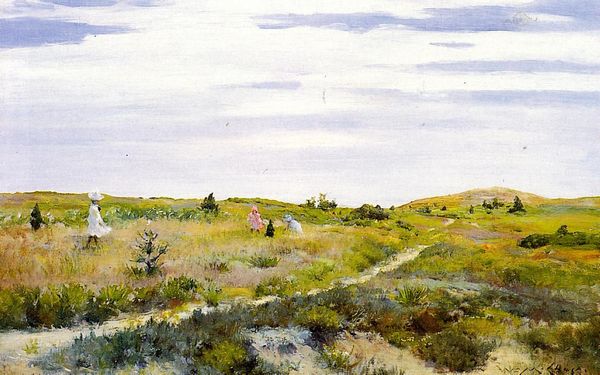

Copyright: Public domain

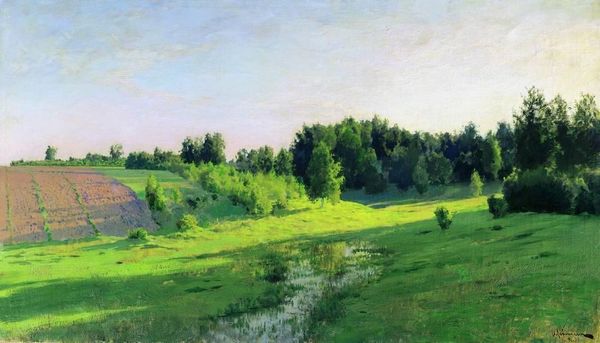

Curator: Before us hangs "Shinnecock Landscape with Figures," painted in 1895 by William Merritt Chase. It offers a view into Long Island's Shinnecock Hills, where Chase established an influential summer school. Editor: It’s immediately appealing. A bright, optimistic scene, suffused with light. The thick impasto of the oil paint really brings the meadow alive, almost tactile. You can practically feel the grass. Curator: Chase was deeply invested in plein-air painting, influenced by the Impressionists. These scenes were often depicted as leisure spots for the emerging upper middle class. Note the positioning of the women; their clothing and social standing signal a lifestyle of privileged leisure. Editor: But even the leisure class is embedded in the processes of labor and production. Looking closer at Chase’s application of paint, the broken strokes aren't just aesthetic. The roughness reminds us of the physical act of painting itself—the artist's labor as a means of production. And, of course, producing the materials of that act is its own type of labor, from grinding pigment to stretching canvas. Curator: Absolutely. The establishment of the Shinnecock Hills Summer School was part of the larger movement to professionalize art education. Chase brought in urban art students, shaping a distinctly American Impressionism while solidifying his own position within the art world. Editor: Yes, and that position gave him the leverage to shape tastes, demands, and thus, the entire market around artmaking in this moment. Consider what went into capturing these seemingly spontaneous, sun-drenched moments. Chase likely used pre-mixed paints available in tubes, signifying industrial contributions to the seemingly untouched landscapes. Curator: True. While Chase's subject is the landscape and leisurely figures, the act of its creation mirrors societal shifts within art production. Editor: The work’s appeal to collectors underscores how even pastoral scenes are thoroughly implicated in material culture and social structures. Seeing these fields as constructed realities reframes them for me. Curator: A perfect synthesis—reminding us that even tranquil images speak volumes about their context. Editor: Indeed, making us consider what, and whom, are not necessarily shown in that seemingly idyllic world.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.