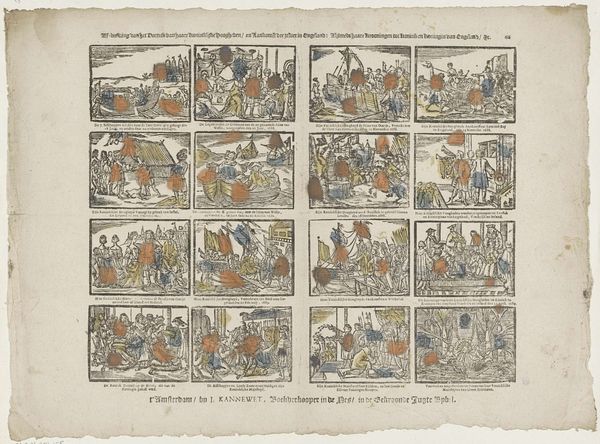

drawing, print, etching, ink

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

caricature

#

ink

#

romanticism

#

genre-painting

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

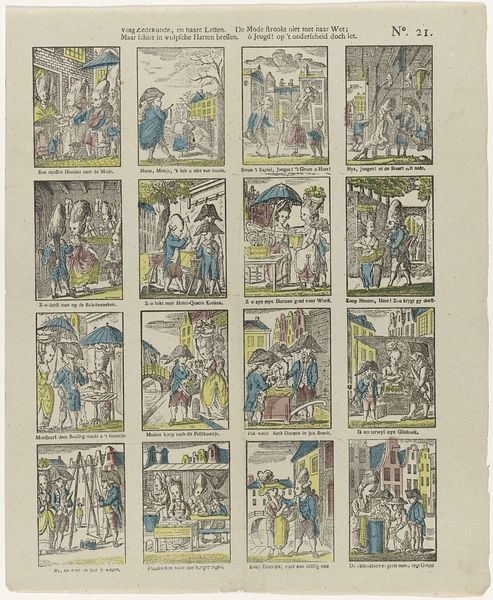

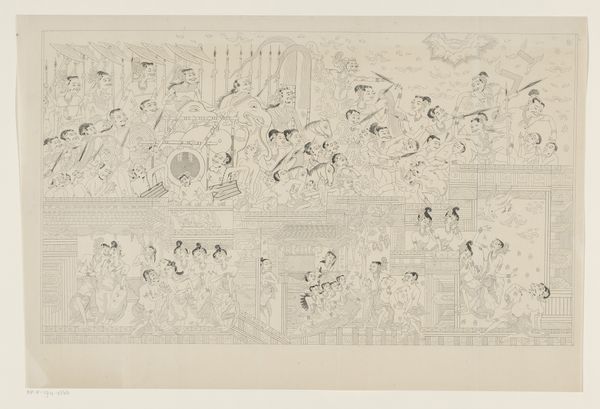

Curator: What a vibrant, bustling image! Rowlandson's "The Boxes," possibly from 1809, explodes with life, doesn't it? Editor: Absolutely. My initial impression is organized chaos. It’s an overwhelming panorama of faces, but with distinct levels and a peculiar theatricality. A playhouse or opera house comes to mind. Curator: It depicts a theatre audience, observed with a satirist's eye. The artist has created it as a print—likely etching and ink—in keeping with his popular caricatures of Georgian society. You can clearly distinguish different strata, can’t you, in the boxes? Editor: I can indeed. I find it intriguing how the artist is capturing not just an audience, but the *act* of being an audience – the shared experience, yet within rigid social constraints. Curator: The symbolic load here is rich. Dogs mirroring the social classes in miniature and children reenacting what adults do – can you see the cultural memories shaping that behavior, how traditions echo through generations? Rowlandson doesn't miss a beat when pointing out the social performance embedded in theatre attendance. Editor: He is incredibly keen to capture the nuances. We see this particularly in the details of fashion, behavior, and how each tier relates to another. Are these established tropes for this social criticism? Curator: Consider the era: these caricatures emerged at a crucial moment of shifting societal structures and theatrical innovations in England, echoing class tensions of the time. This reflects the emergence of public life and how identity, politics, and entertainment intersect, making prints powerful public art. Editor: Very good point! These figures could then consume their public image en masse at relatively low cost, solidifying the theatrical experience long after their night out. They themselves become actors even offstage. It seems the very act of *observing* becomes its own spectacle. Curator: Precisely! Every row is a stage within a stage, revealing the absurd dance of observation itself. These echoes remind us that we all participate in a constant social performance, mediated through inherited customs. It seems relevant to modern screen consumption, right? Editor: Absolutely, the piece acts as a historical mirror to current consumption habits, offering insights into how public imagery continues to shape behavior. Fascinating parallels between Rowlandson’s commentary on spectacle and today’s obsession with screens!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.