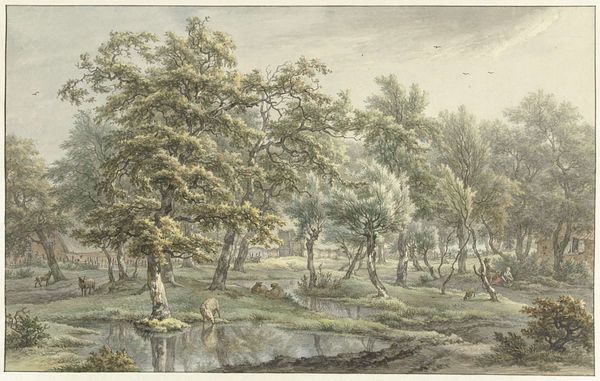

Dimensions: height 190 mm, width 245 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: We're looking at "Wooded Landscape with Rider and Pond," a drawing attributed to Jacobus Versteegen, dating roughly between 1745 and 1795. It’s currently held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My immediate impression is one of melancholy, a quiet, almost somber scene. The greyed watercolors evoke a sense of subdued reflection. Curator: Indeed. What strikes me is the labor-intensive detail despite the understated color palette. Consider the process of preparing watercolors during that period, grinding pigments, and the skill required to achieve such subtle tonal gradations. It suggests a deliberate act of meticulous craftsmanship for a presumably elite consumer. Editor: And those tonal gradations contribute to the atmosphere. The forest, a consistent symbol throughout art history, here feels like a space between worlds, liminal. The lone rider could be anyone, journeying towards something unknown. It resonates with themes of Romanticism – the individual confronted by the vastness and mystery of nature. Curator: Interesting. I wonder about the accessibility of this 'vastness.' For whom was this constructed natural world designed? The inclusion of a rider suggests leisure, ownership of both time and land. Even in its apparent 'naturalness', there is a careful construct related to consumption and social order at play. Editor: True. The pond also acts symbolically; water has always represented the unconscious, reflection, perhaps even danger. The rider's position near it implies a contemplation of something deeper, more emotional, than simply a pleasant horseback ride. It's more about internal navigation. Curator: Perhaps it reflects the internal landscape of the emerging bourgeois class. These cultivated environments, though appearing "wild," reflect an order, both aesthetic and social, meticulously fashioned and preserved for certain eyes. We might even examine trade relations of pigment and paper to reveal underlying systems of power and colonial economies in the availability of these "natural" colors. Editor: That adds another layer to my reading of the image. I saw primarily personal introspection in those early symbolic elements. Knowing what kind of person was supposed to "consume" such an artwork affects what one perceives. The composition, material conditions and thematic underpinnings are inextricably linked here. Curator: Precisely. What we're observing isn’t a simple "landscape" but a layered statement about 18th-century society viewed through its productive relationships with nature and its place in the emerging world-system. Editor: Seeing beyond the solitary rider, recognizing their relationship to both land and product gives me a new point of view. Thank you for pointing me toward the physical work and the historical meaning of what's outside, as well as inside, the artistic content.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.