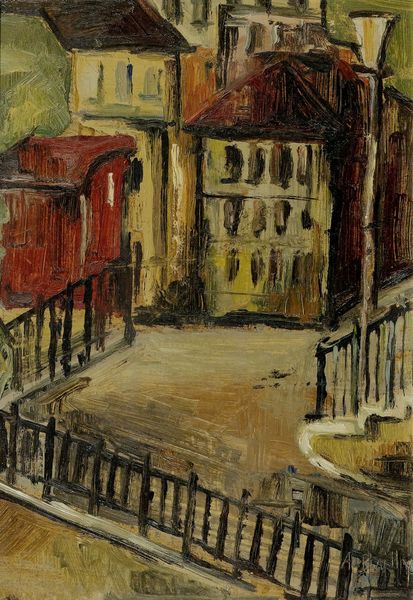

Copyright: Public domain

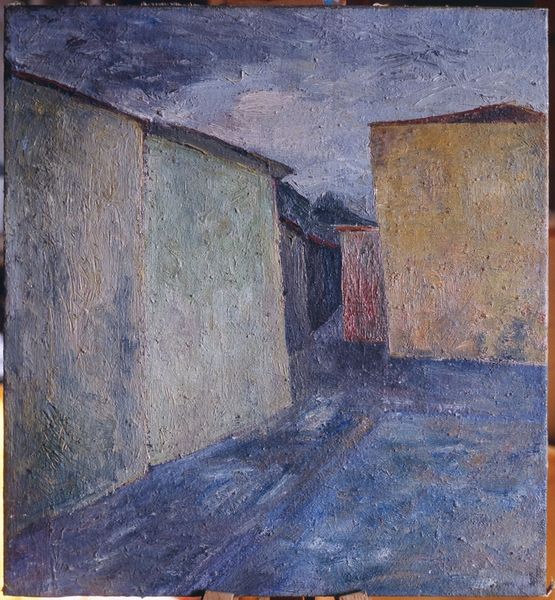

Curator: This is Antonio Carneiro’s "Rua Bretã," painted in 1899. It’s an oil painting done en plein air, showcasing a street scene rendered in the Post-Impressionist style. Editor: My first impression is one of stillness, almost hushed. The color palette is muted, largely browns and ochres, and the brushstrokes give the scene a dreamlike quality, like a memory fading at the edges. Curator: Yes, that stillness is key. Carneiro, although Portuguese, spent formative time in Paris, absorbing Impressionist techniques. "Rua Bretã," though, feels less about capturing fleeting light and more about evoking a sense of place, a feeling of Brittany, which was also attracting many other artists during the time. What do you make of that? Editor: The shadows definitely contribute to that stillness. Notice how they are cast so boldly, suggesting a strong light source but also a sense of something hidden, a quiet mystery perhaps residing within those dark, aged buildings. The almost uniform application of the colors builds this quality, like an old tapestry whose vivid colors have become uniform with age. What street and buildings inspired the picture? Curator: Unfortunately, we can't be sure precisely where he painted it, as the "Rua Bretã" is simply Portuguese for "Breton Street", but this allows us to discuss the image from other critical perspectives. Consider the era when this was made. Many rural regions were rapidly losing their local populations and cultural identities as urbanization lured younger people into big industrial centres. This landscape evokes what rural populations felt then: their imminent passing. What remains today? Editor: That is thought-provoking. Looking at the details now, the lack of people truly makes this image even more somber than I initially thought, it echoes similar urban landscapes of empty streets made after tragedies or during war times, but the buildings and street textures definitely have a melancholic beauty and even hope that they remain standing as time passes by. Curator: Absolutely. This tension is, perhaps, what makes the painting so compelling: the interplay between capturing the ephemeral nature of light, while gesturing to its place in a broader network of rurality, urbanity and migration in post-industrial European society. Editor: Looking again, I now interpret its beauty and calmness, mixed with some sorrow, as an eternal beacon: it has been standing in a world for some time and will likely remain standing after we disappear from it. It's definitely impressive how art may reflect feelings that may come at different times and points in history, remaining as important as when it was first painted.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.