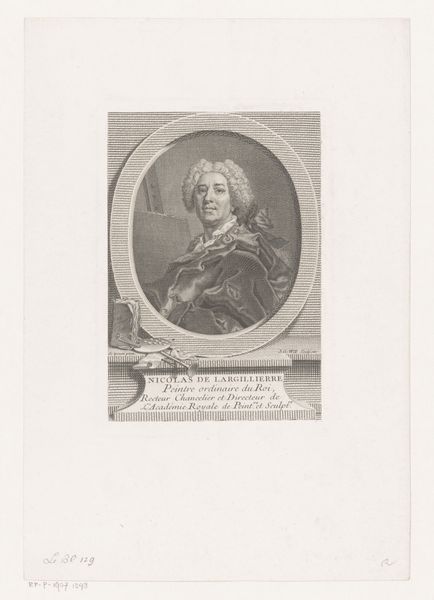

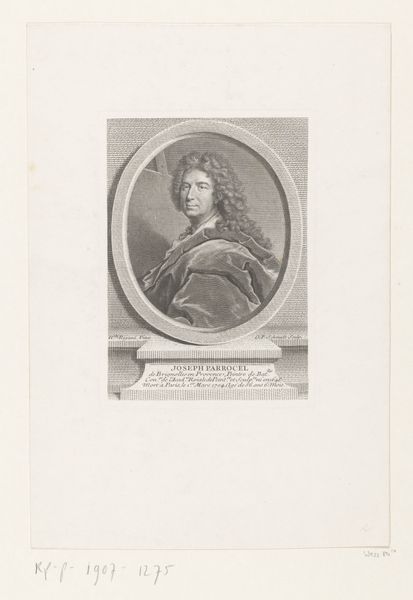

print, etching, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 435 mm, width 341 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Pierre Drevet's "Portret van Hippolyte de Béthune," dating from around 1673 to 1738. It’s an etching and engraving, so a print, displayed at the Rijksmuseum. The detail is incredible. What’s most interesting to you about this piece? Curator: Immediately, I'm drawn to the process and materials used to create this print. Engraving and etching demand a specific kind of labor. Think about the engraver’s workshop, the cost of copperplates, the physical act of cutting into metal—these were commodities themselves. It wasn't just about representing the Bishop; it was about production. Editor: That's interesting. I hadn't considered the economic side. Curator: Precisely! Consider how the materials available, or the skill of the artisans, shaped the final image. This isn’t simply an objective portrayal; it’s mediated by the conditions of its making. How accessible were such prints to the public, and how did their cost relate to other commodities of the era? Editor: I suppose owning this print conferred status, reflecting the Bishop's own high standing, or the purchaser. It feels like owning a portrait twice removed. Curator: Exactly! This mediated representation and its material production become crucial to understanding its value. Do you think this changes our understanding of the portrait tradition? Editor: It does shift it. The portrait isn't just about likeness or status anymore; it’s a material object embedded in a web of social and economic relations. I learned a lot from this. Thank you! Curator: Indeed, by examining the labor, materiality, and consumption surrounding this print, we gain a deeper appreciation for its complexity. Thanks for walking through it with me!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.