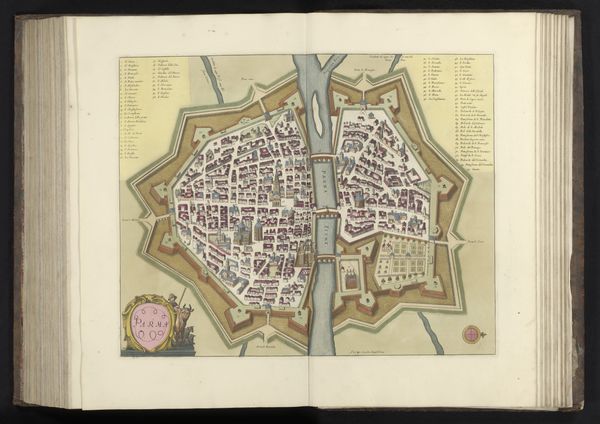

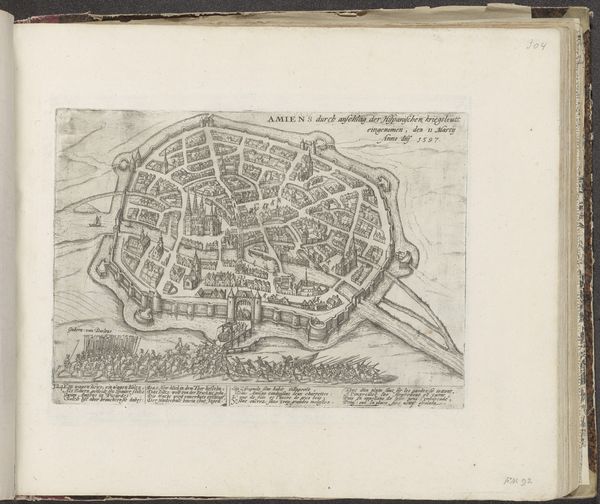

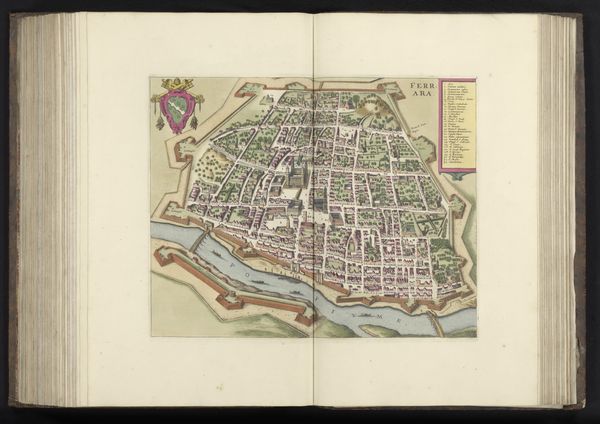

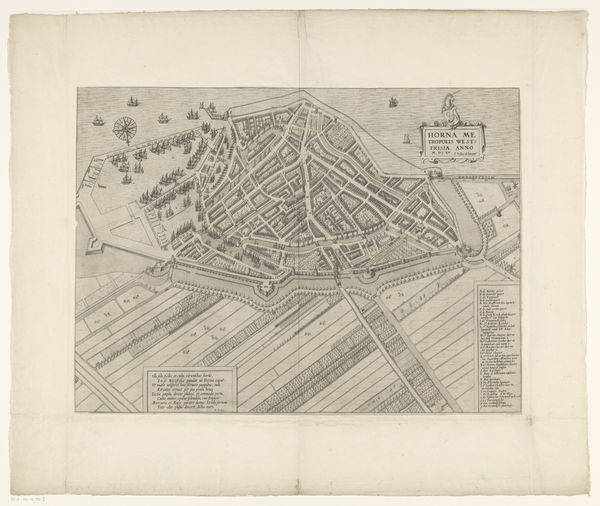

Gezicht op Viterbo in vogelvluchtperspectief Possibly 1617 - 1717

0:00

0:00

wenceslaushollar

Rijksmuseum

drawing, print, etching, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

paper

#

ink

#

cityscape

Dimensions: height 379 mm, width 427 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome. Before us, we have "Gezicht op Viterbo in vogelvluchtperspectief," a bird’s-eye view of Viterbo. The Rijksmuseum attributes this drawing, a print made with etching on paper and ink, to Wenceslaus Hollar, placing it somewhere between 1617 and 1717, an interesting spread. Editor: It strikes me as surprisingly...oppressive. I mean, from a bird's-eye perspective, one might expect freedom, a sense of openness. But the walled city, that density, speaks of constraint and control. The social dynamic would be one of control within. Curator: Exactly. Considering the period, and especially within Italy, cityscapes such as these represented not just cartographical documentation, but assertions of power. Walls physically divide inside from outside. This allowed those on the inside of the walls to protect their resources and exercise absolute control over the territory and its resources. It illustrates that society was structured, who could access what was tightly defined, and who was left on the outside was just as significant. Editor: You can see this through the very details that compose this etching, a bird’s-eye view but very tightly defined within the constraints and social-political control. Take, for example, the abundance of church spires even in the distance. These religious structures are a very visual demonstration of ideology in this setting and show control in spiritual ways, as well. It’s visual language makes me believe it could also have propaganda value as much as to map a particular territory, what do you think? Curator: I'm absolutely with you. Consider the historical role of Viterbo; popes resided here in the 13th century. So what you are seeing with an abundance of religious spires are more than aesthetic elements and function beyond its beautiful architectural impact, their placement emphasizes this connection between temporal and divine authority. Hollar, or whoever created this work, uses the visual vocabulary of the time to reinforce that hierarchy. The iconography creates a world where control and divine favor intertwine, dictating who could access territory and what spiritual access could be granted. Editor: So, beyond its geographical function as a landscape or the physical layout of the city, this bird’s-eye view shows an image that attempts to define the cultural values that are actively projected to preserve, perhaps? Curator: Precisely. It gives insight into the anxieties and the ambitions of the city, not just where things *are*, but how its controllers wanted to be seen within it. Editor: It makes one reflect how cities continue to be self-representations, ever since this print, which continues today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.