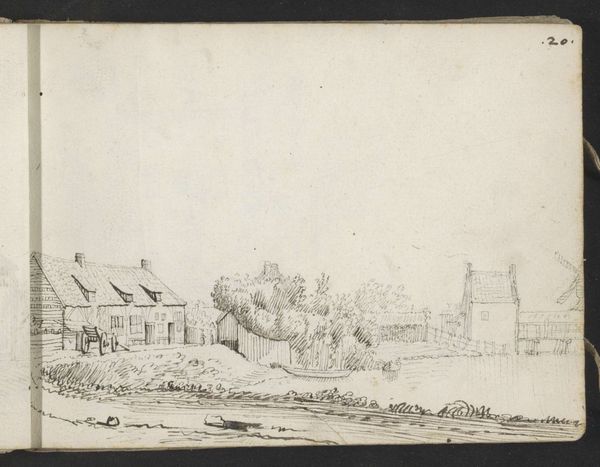

drawing, paper, watercolor

#

drawing

#

landscape

#

paper

#

watercolor

#

romanticism

#

watercolour illustration

#

genre-painting

#

watercolor

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

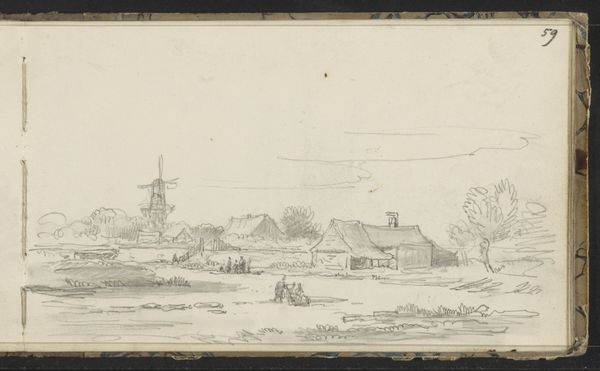

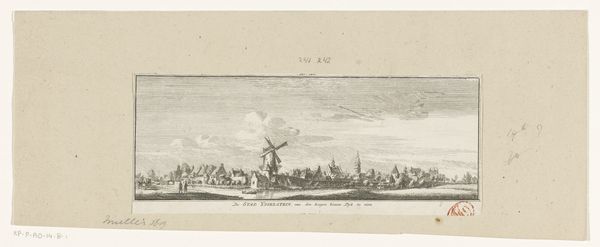

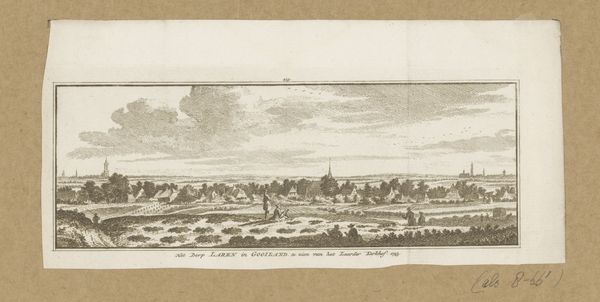

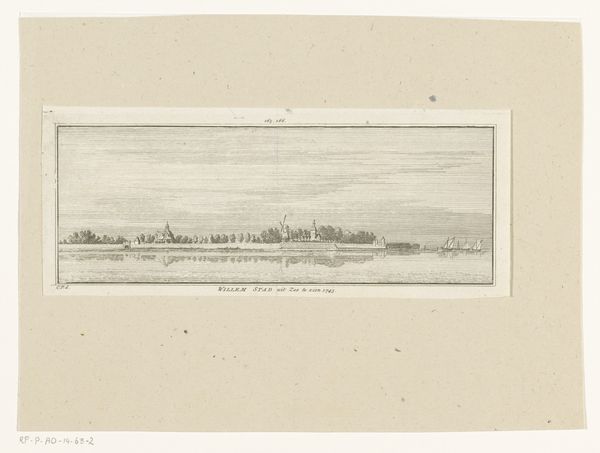

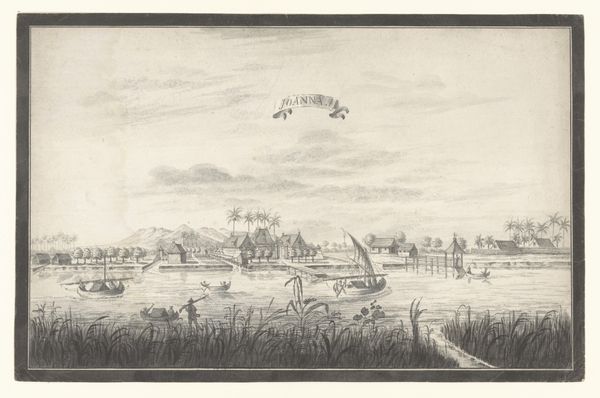

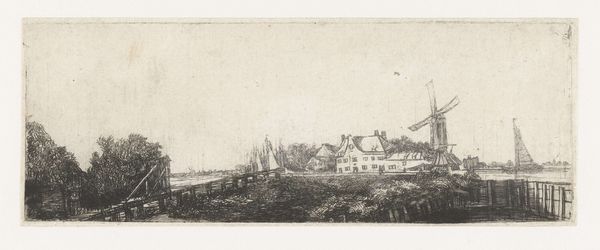

Curator: Hendrik Abraham Klinkhamer created this work, "Landscapes with a Mill and a Farm," between 1820 and 1872. It's currently held in the Rijksmuseum. He employed watercolor on paper to give us this glimpse of the Dutch countryside. Editor: Oh, it's wonderfully muted, isn't it? A very gentle melancholy washes over me. Almost like a half-remembered dream from a summer long past. Curator: Indeed. The composition is quite interesting too. Klinkhamer seems to be exploring themes prevalent in the Romantic era. We can see how this genre scene situates agricultural life within broader socio-economic changes happening at that time. Consider how the rising urban centers might have shaped his nostalgic views. Editor: Nostalgic, yes, perfectly put. It almost feels like a study in contrasts. Two worlds layered upon one another, the simple life above and the mechanics of providing for it down below. It lacks detail, of course, being a watercolor drawing and yet manages to fill our minds with specific visions of farmlands and the structures built there. It reminds me, oddly enough, of some haikus about quiet mornings in rural Japan. Curator: That connection to Japanese haikus is intriguing. But I would argue there is also an element of the political embedded here. The land isn't just a backdrop; it is where labour takes place and thus is a nexus of class relations. Klinkhamer is not just showing us pretty buildings and pastoral calm, but hinting at hierarchies within this supposedly idyllic setting. Editor: Hmm, hierarchies, you say? Perhaps. Or maybe it is just yearning, just an artist drawn to capture an honest image of the landscape. We mustn't forget that it might be just about beauty. Simplicity can be profound. Curator: Simplicity, though, never exists in a vacuum. Even these seemingly gentle lines and pale colors, these windmills and farmhouses, whisper of labor, of ownership, of a changing society and it's impacts on who could claim beauty as an aesthetic standard. Editor: I concede your point; context is always important, even if, on some level, I want to reject such critical analysis. Still, this sketch carries with it its social position whether it strives to or not. Curator: Well, it's precisely that tension between aesthetic experience and sociopolitical context that makes examining pieces like this so compelling, isn't it? Editor: It truly is! Thanks for drawing that to light.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.