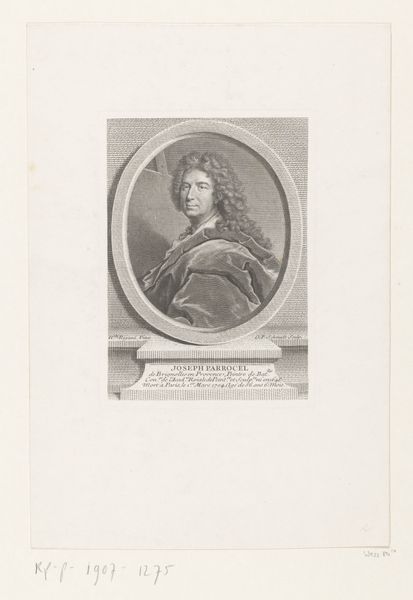

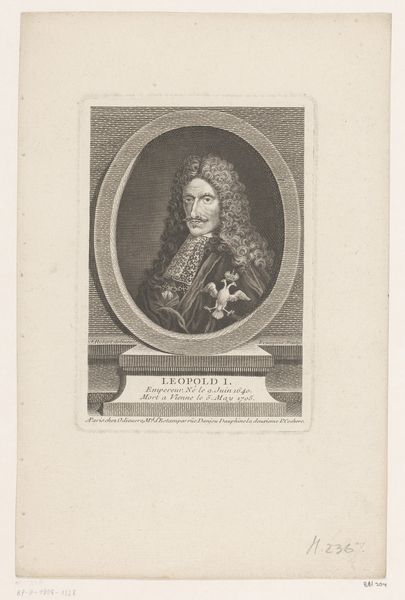

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 371 mm, width 263 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Jean-Baptiste de Poilly's 1714 engraving, "Portret van Corneille van Clève." The way the subject is framed in an oval gives it the air of a monument, and I'm struck by how theatrical it feels. What are your initial thoughts on this print? Curator: That theatricality is key. Think about the socio-political landscape of 18th-century France: portraiture became a powerful tool for constructing identity and projecting status. This image of Corneille van Clève isn't simply a likeness; it's a carefully crafted representation of a figure associated with the royal court. Editor: So it’s more about status than personality? Curator: Precisely. The baroque style – the swirling drapery, the elaborate wig – speaks to a culture obsessed with spectacle and grandeur. And this image circulated as a print, what does that tell us? How might that change our perception of Corneille van Clève's power and reputation at the time? Editor: It suggests his image was meant for a broader audience. This wasn't just a personal memento but something to disseminate. It's almost like a publicity stunt! Curator: Exactly. Think about how the *Académie Royale*, mentioned in the inscription, benefited from associating with a figure like Clève. These institutions actively shaped artistic tastes and maintained power structures. This image participates in that. Editor: It’s fascinating to consider how something as simple as a portrait could play a part in larger power dynamics. Curator: Indeed. It demonstrates how art actively shapes society's memory and reflects power structures, rather than passively mirroring them. Editor: I see it now. It's less about capturing the individual and more about reinforcing societal norms. Curator: It’s important to always consider art’s place in the society that birthed it!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.