Dimensions: height 298 mm, width 184 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

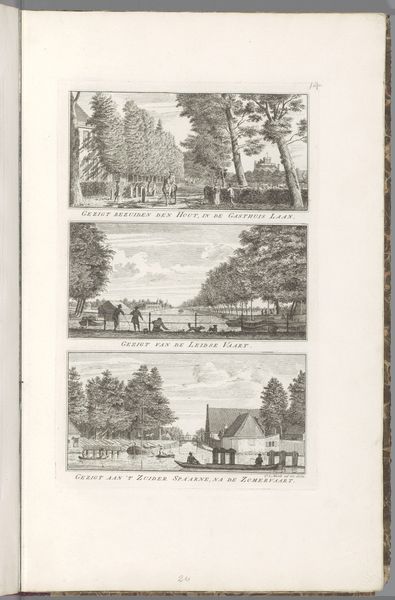

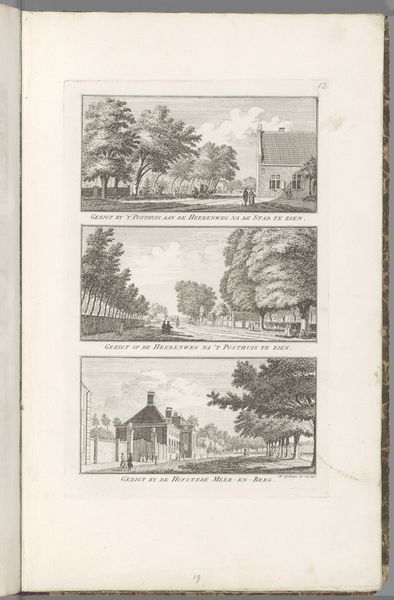

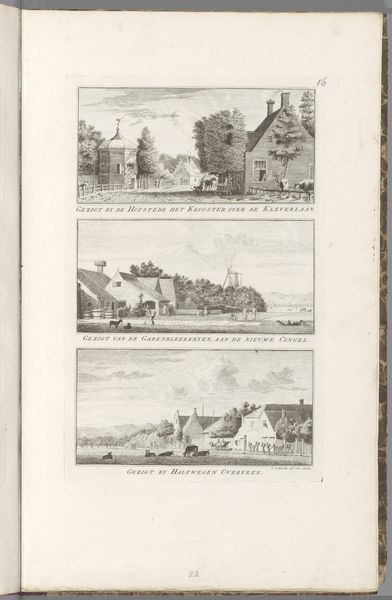

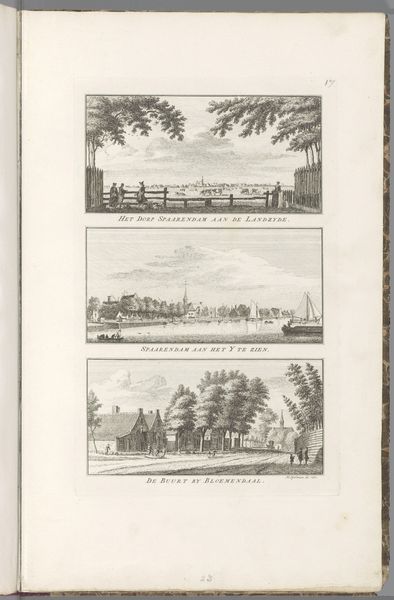

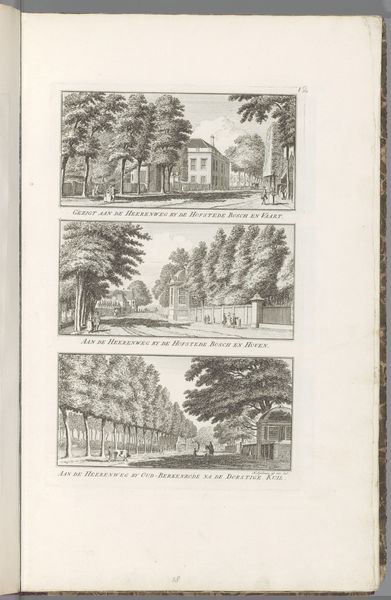

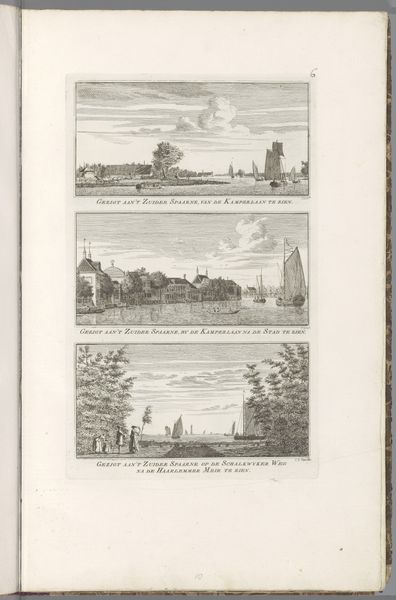

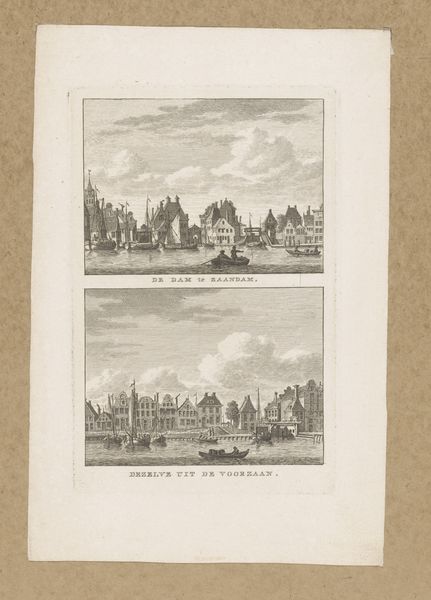

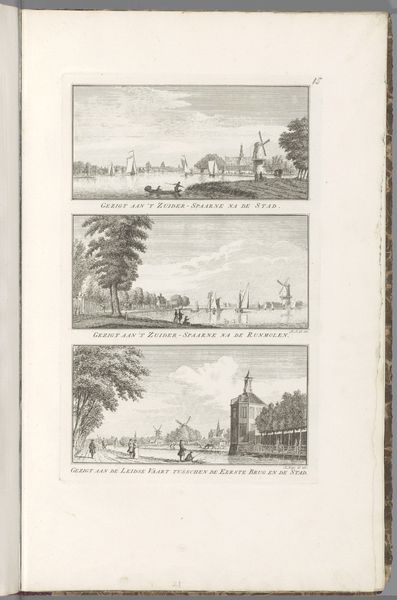

Curator: Here we have "Gezichten op landschappen bij Overveen en Bloemendaal," or "Views of Landscapes near Overveen and Bloemendaal" created in 1763 by Cornelis van Noorde. This piece from the Rijksmuseum is an etching, engraving, and print all in one. Editor: My first impression is of order. A series of landscapes stacked neatly on the page, a bit like pressed botanical samples or surveying documents, each captured with meticulous detail. Curator: Right, let's consider that meticulous detail. Van Noorde was a draughtsman, etcher, and engraver, focusing primarily on topographical representations. He documents these locations around Overveen with sharp detail, almost clinical in its exactitude. What social forces might shape such work? Editor: The rise of the middle class, for starters. They needed affordable art for their homes, art that reflected their world. Prints made that possible, democratizing art consumption in a way previously unheard of. Consider the labour; one plate, multiple impressions, spread across a widening marketplace. Curator: Precisely! The print becomes a commodity. But also consider the emerging scientific impulse; to classify and document the natural world. This resonates with the broader context of the Enlightenment and the evolving public role of artists as observers of the everyday world. Editor: Absolutely. Each etching seems deliberately chosen to project images of productivity. Fields and paths suggest agriculture. Also, the lines etched in the copperplate dictate not only perspective but also the perceived textures of the landscape. Curator: It brings up interesting considerations around artistic labour itself, doesn't it? Van Noorde clearly prioritized capturing recognizable representations. Did he regard this as simply a craft, or were there artistic intentions present as well? Editor: He had to possess great technical skill. The act of engraving is, in itself, highly skilled manual work. Yet, it raises a wider social question. In an age of canals and trade, could we understand this landscape through material flows? The barges going up the Jan Gijzenvaart carrying goods. Curator: Indeed. Each small rendering becomes evidence of broader shifts within society itself, doesn’t it? Editor: Reflecting upon that, it appears this etching isn't just a pretty view, it shows social movement, processes, and people that relied upon these land for survival and recreation. Curator: Well, it has given me plenty to think about in terms of art patronage and public engagement back in the late eighteenth century. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.