drawing, plein-air, pencil, architecture

#

drawing

#

16_19th-century

#

plein-air

#

landscape

#

etching

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

architecture

Copyright: Public Domain

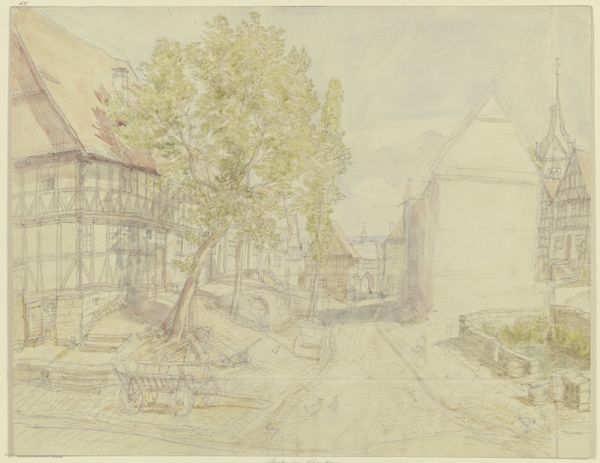

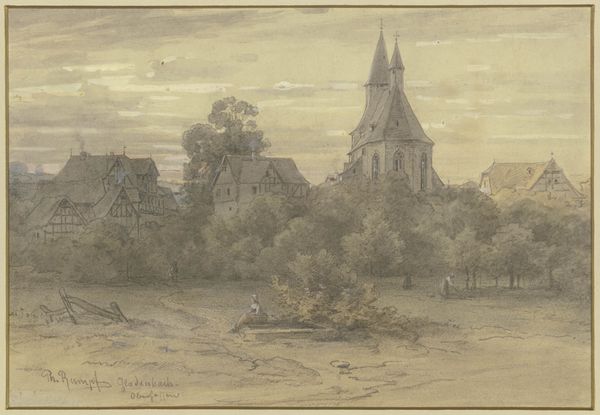

Curator: This delicate pencil and etching drawing, titled "Partie am Ausfluss der Wisper," which roughly translates to "Scene at the outflow of the Wisper River," by Peter Becker, transports us to a quaint riverside village. Editor: It’s wonderfully evocative. The softness of the lines gives it a dreamlike quality, like a half-remembered place from childhood. It feels peaceful, almost melancholic. Curator: Becker’s choice of plein-air, which focuses on open-air work, aligns with the broader Romantic movement fascination with nature. These direct sketches become essential reference points. The very act of sketching outside was laden with symbolic value. It reflected a more authentic and direct encounter with nature, untainted by urban life. Editor: I see the quiet confidence of enduring archetypes, though. The steeple, for example—that spire has always pointed humanity toward the heavens, towards faith. Then you have the bridge over water, a classic symbol of transition, of moving from one state to another. Even the trees feel significant; they represent organic growth, stability, deep-rooted connection. Curator: Right, and consider the Wisper river itself. Rivers in art often symbolize the passage of time, change and constant flux. In terms of political history, it represents how boundaries have developed through urbanization and settlement around these water sources. Editor: It gives this scene more weight, beyond just a pretty view. I am drawn to how this depiction of water also echoes psychological dimensions. Reflective surfaces can represent introspection or unconsciousness, and considering Becker created this work in situ allows the view to perceive beyond the architectural constraints into its internal form. Curator: Well put. In its deliberate understatement, Becker seems to invite contemplation. He offers us a glimpse into the relationship between rurality, spirituality, and the ever-changing landscapes of nineteenth-century Europe. Editor: Exactly. We’re left pondering what “home” truly means—not just a place, but also an accumulation of collective beliefs, environmental transformations and continuous transition into the future.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.