daguerreotype, paper, photography

#

portrait

#

16_19th-century

#

daguerreotype

#

paper

#

photography

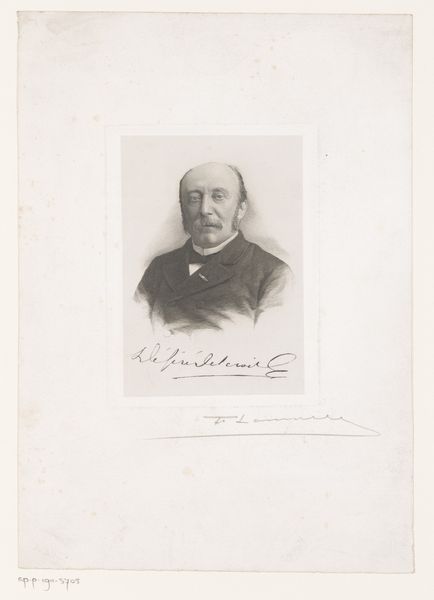

Dimensions: 22.7 × 18.3 cm (image/paper); 32 × 26 cm (mount)

Copyright: Public Domain

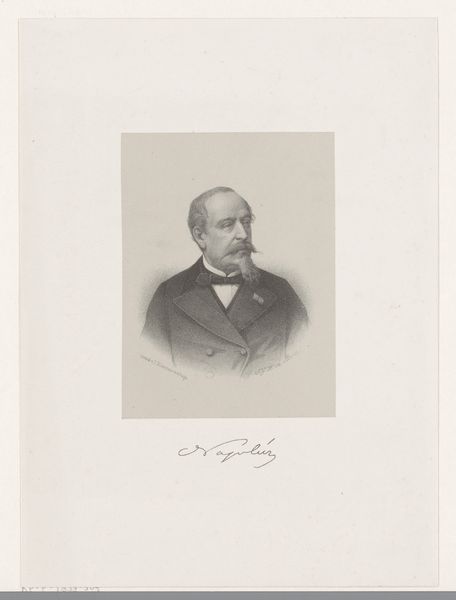

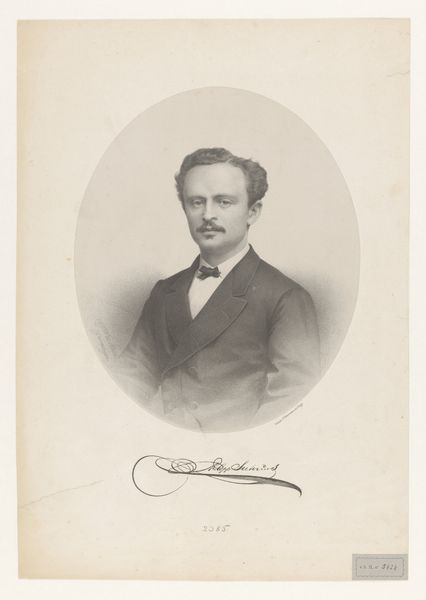

Curator: Looking at this portrait, I’m immediately struck by the subject’s somewhat melancholic gaze. There’s a quiet intensity that feels very personal, even though it’s a formal studio photograph. Editor: This is Édouard Siebecker, in a photograph by Etienne Carjat, sometime between 1876 and 1884. What fascinates me is the labor involved in creating these portraits. It was a very meticulous process, beginning with the production of sensitized paper necessary for capturing the image, extending all the way through to how it’s presented here, mounted on this larger sheet. Curator: Absolutely. It's easy to forget the technical and chemical expertise required. Beyond that, though, how would this image have functioned? Was this for public display, private collection? The Galerie Contemporaine imprint suggests a degree of wider dissemination. Editor: Likely both. Dissemination and the idea of public consumption become key. Consider the context – photography in the late 19th century becoming increasingly democratized but still demanding a level of skill. The daguerreotype process allowed for relatively quick production, which is why portrait studios blossomed. Also, thinking about paper itself as a precious commodity allows one to explore social status here. Curator: So, the very materials of the portrait themselves become indicators of access and status. Do you think that democratization altered artistic approaches and even perceptions of social class? Editor: Undeniably. It introduced anxieties, too, particularly for artists accustomed to more traditional mediums. The rise of photography forces painting to confront its role and its modes of representation. Carjat himself, of course, was known as a caricaturist. I’m certain the speed with which one can take these photographs had an effect. Curator: The subject looks like someone between roles, as if representing many at once—almost capturing an emergent, bourgeois, in-between state in his identity through dress and facial expression. Perhaps what strikes me as melancholy is the weight of that transition? Editor: Yes, it really brings into focus that constant tension of social structures constantly attempting to solidify themselves and the materials needed to reflect it, even through a mere portrait. Curator: Well, it seems our explorations have deepened my initial impression. It’s remarkable how material and historical considerations amplify the image's emotional depth. Editor: Indeed. It transforms it from a mere likeness to a cultural object embedded in a web of labor and societal forces.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.