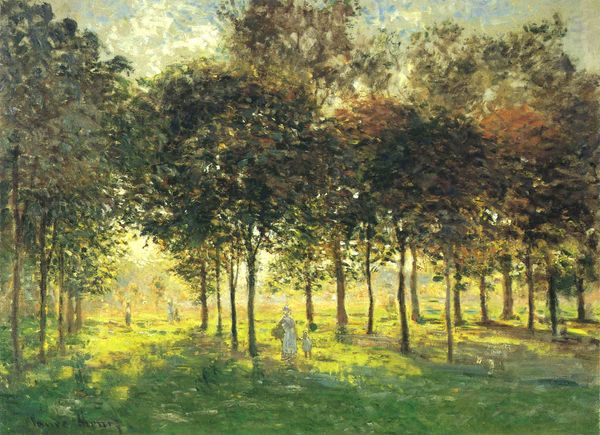

Copyright: Public domain US

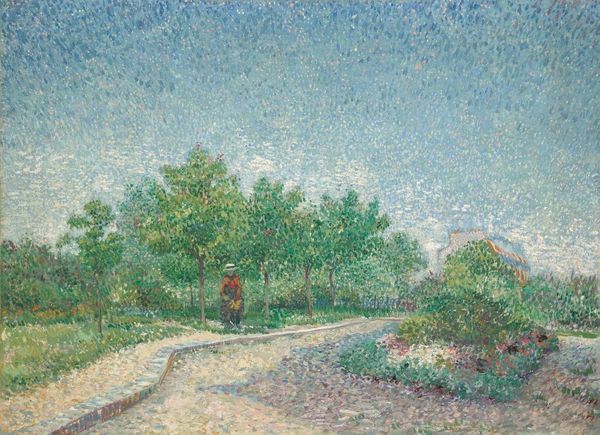

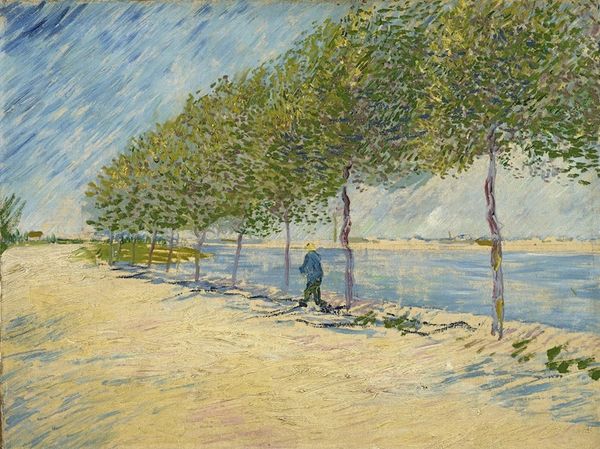

Curator: Today, we're exploring "Un Paseo en el Parque," or "A Walk in the Park," a painting by Armando Reverón, dating from 1922. It’s an oil on canvas, done in a plein-air style. What’s your first impression? Editor: It feels...dreamy. Ethereal. There’s a quiet loneliness to it. The muted colors and hazy atmosphere give it a sense of distance, even melancholy, despite depicting something as simple as a park. Curator: The impressionistic technique, capturing light and atmosphere, certainly contributes to that effect. The symbolism of the park itself is quite interesting—a space of leisure, nature, and societal mixing. In many cultures, parks are deliberately cultivated spaces. Editor: Yes, and that very cultivation hints at the illusion of accessibility, especially when we consider that the 'right' to enjoy spaces like these have historically been restricted by social status and class. I am reminded of conversations around public spaces. Is it truly accessible for everyone? Who gets to feel safe and welcomed here? Curator: A pertinent question, always. But Reverón's impressionistic, almost hazy style does not reflect any social or class perspective; rather, it dissolves sharp edges to reveal light and its effects, conveying almost pure sensation. We see this atmospheric dissolving elsewhere in his art as well, reflective of what Reveron named "lyrical period" - almost an attempt to evoke feelings beyond just sight. Editor: True, there’s also a figure—likely a woman based on the dress and silhouette, but rendered almost faceless. She is on the edges of the canvas. She’s alone, which deepens the earlier sense of solitude. It asks you to reflect upon women’s role within such a park. Or lack thereof. Curator: Or maybe, the joy of solitude. Maybe she reflects personal peace within such green expanses. Editor: I concede the piece isn't overtly critical; still, I'm attuned to these details. They shape the larger cultural story and echo lived experiences for women across time and geographies. Curator: In that, it's reflective. Its power, then, rests not in stark depictions, but invitations to reflect, to *feel* beyond what we’re seeing on the canvas, the effect light has on atmosphere, memory, and symbol. Editor: Right. And perhaps, by acknowledging the underlying tensions in even the simplest scene, it calls us to keep working towards creating truly welcoming spaces, ones where everyone feels that peace.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.