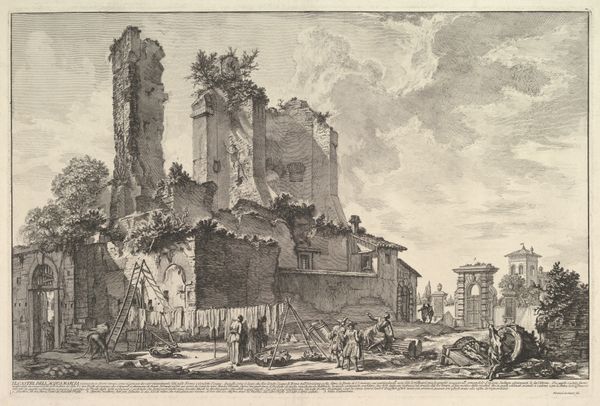

Saint John's Cemetery with a View of the City of Nuremberg, from Collection of Memorable Medieval Buildings in Germany 1819

0:00

0:00

drawing, lithograph, print, paper

#

drawing

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

germany

#

lithograph

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

sketch book

#

paper

#

unrealistic statue

#

carved into stone

#

19th century

#

watercolour illustration

#

pencil art

#

watercolor

Dimensions: 385 × 416 mm (image/text); 486 × 555 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Before us is Domenico Quaglio's "Saint John's Cemetery with a View of the City of Nuremberg," a lithograph created around 1819, held at The Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: It's quite stark. The monochromatic palette amplifies the gravitas. Those crucifixes looming over the cityscape feel both imposing and somber. Curator: Indeed. Quaglio uses the imagery of the crucifixion to convey profound cultural memory. The three crosses dominating the composition evoke a sense of communal suffering and redemption, themes deeply embedded in German cultural consciousness. The Nuremberg castle visible in the distance acts almost as a counterpoint. Editor: It’s fascinating to consider the materiality. This isn't some grand oil painting; it's a lithograph, a more accessible medium at the time, allowing for wider dissemination. It implies a conscious choice to bring this vision, these loaded symbols, to a broader audience beyond the wealthy elite. What's striking to me is that it appears that much of the image, even the figures on the crosses and city itself, were produced with something that looks more akin to a pencil sketch instead of painting with brushes. Curator: Absolutely. Lithography enabled the rapid reproduction of images, further democratizing art and disseminating powerful symbols. The aged, toned paper adds another layer, connecting us to the passage of time and reinforcing themes of historical memory. Observe how the horizon line separates earthly struggle, the cemetery, from a city, symbolizing a complex relationship. Editor: It also calls to mind labor. Each print would have required skilled artisans to prepare the stones and run the presses. We aren't merely looking at artistic vision, but at a collaborative manufacturing process tied to a specific economic moment in 19th-century Germany. It is less about the "artist" and more about artistry by many unknown hands. Curator: A fruitful point! It underscores the print's nature as an object produced through labor but invested with a potent combination of Christian iconography, national identity, and remembrance. The crosses become shorthand for centuries of faith, even in death and grief. Editor: Precisely. And through the lens of materiality, it serves as a tangible relic, its social meaning shaped as much by production as representation. An inexpensive artwork made available on demand that captures a sacred landmark within Germany. Curator: It's remarkable how a simple drawing etched in stone can unlock so many layered perspectives and understanding. Editor: I agree; observing how and why it was produced reveals its real depth and cultural endurance.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.