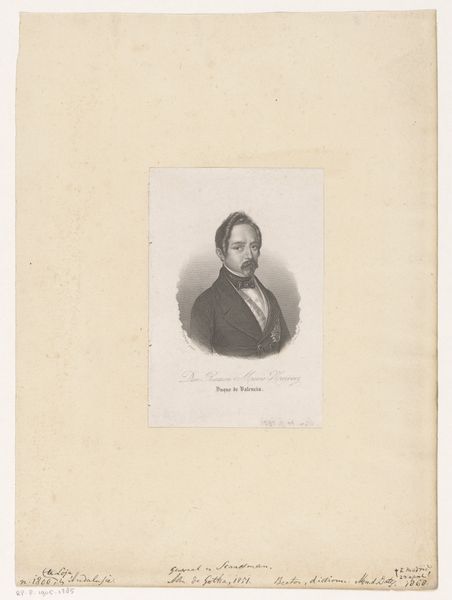

print, daguerreotype, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

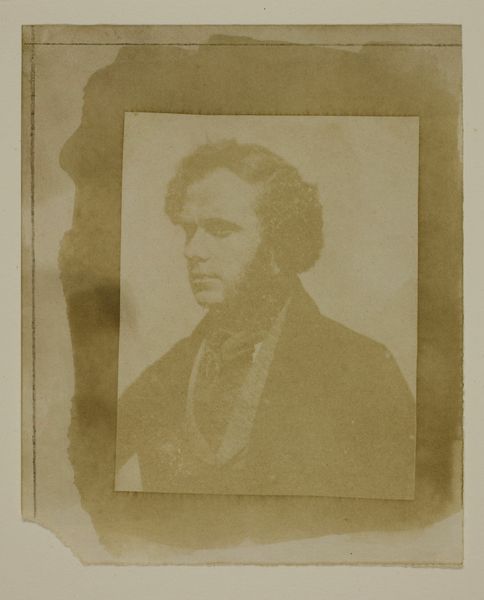

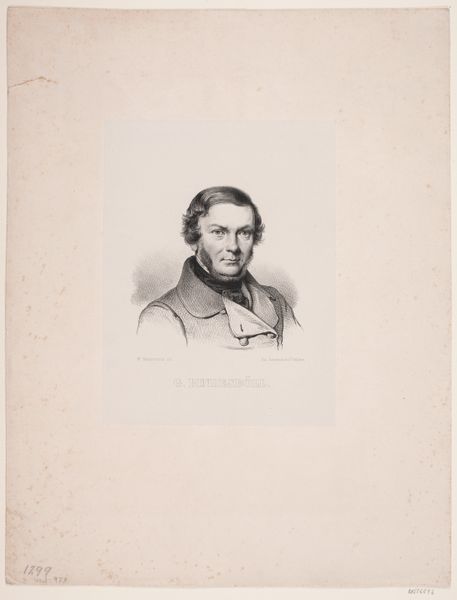

portrait

# print

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

romanticism

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

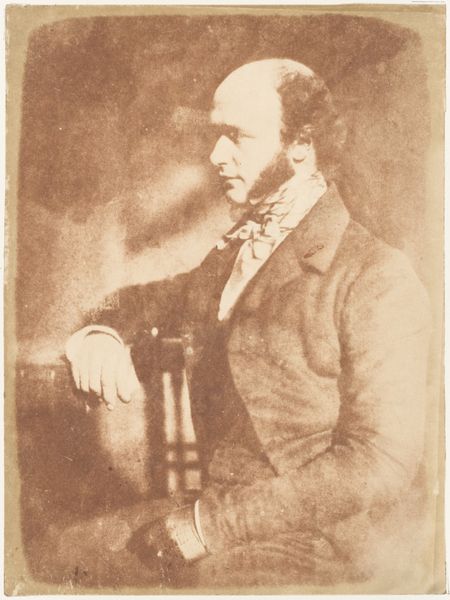

profile

Dimensions: Image: 3 3/16 × 2 1/2 in. (8.1 × 6.4 cm) Sheet: 4 1/2 × 3 11/16 in. (11.5 × 9.3 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Well, isn't this sepia-toned image simply captivating? There's a dreamy, almost ethereal quality to it. Editor: Indeed. This is William Henry Fox Talbot's "Nicolaas Henneman in Profile," dating back to 1843. It’s a fascinating piece of early photography. It definitely possesses this hazy, romantic feel, but what strikes me most is its implicit statement on portraiture at the dawn of photography. Curator: A statement, you say? How so? I mean, he's just standing there, looking pensive, but beautifully nonetheless. What's truly remarkable, I think, is the vulnerability it holds in the very making of its art. It feels as if Talbot almost revealed himself when printing this, his breath upon the print surface. It is like peeking at something that it wasn't supposed to be revealed. Editor: Precisely. Photography initially faced questions regarding its ability to capture truth, right? This, however, makes the argument for an essential role of human mediation through the use of romantic framing. Look how the profile perspective evokes classical sculpture, an era deemed more refined in taste and principle, or that the focus is soft—intentionally, I’d argue—blurring the boundary between objective representation and subjective interpretation. Curator: Yes, blurring those lines… Almost as if Talbot is acknowledging that even in the age of mechanical reproduction, human feeling, artistic soul, remains embedded and it shouldn’t fade out in the portrait! The image isn’t as stark or crisp as, say, a later daguerreotype might be. There is a touch, truly unique, a romantic haze you might feel by seeing one another for the very first time. Editor: And thinking of it as an argument…it subtly challenges traditional hierarchies in art, right? It’s suggesting that the photographer isn't merely a technician but also an artist, capable of imbuing a portrait with emotion, with context, maybe even a little drama. Consider the revolutionary aspect of democratizing images during that period…it might represent even social and class mobility by accessing the field of art. Curator: That's a beautiful point; it becomes this subtle act of social commentary in itself. And just marveling at how such a quiet image can hold such profound dialogues! A trace of someone once here. A mirror into someone's deepest and sweetest thought. Editor: Absolutely, and that is precisely where its power resides: its capacity to ignite these conversations across time and history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.