painting, oil-paint

#

allegory

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

figuration

#

oil painting

#

romanticism

#

mythology

#

history-painting

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

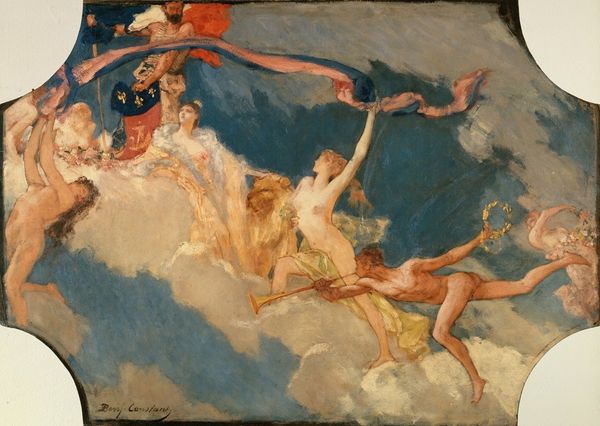

Editor: This is Isidore Pils’ “Minerva Combating Brute Force,” made with oil paint sometime in the 19th century. There’s something unfinished about it, especially in the top corners; you can see some bare canvas. How do you interpret this work? Curator: We should examine Pils' method of production here, and also what "brute force" might have meant to a 19th-century audience. The unfinished quality points to it perhaps being a study, and studying what? The materials themselves speak to a culture embracing industrial output: pigments mixed with linseed oil, stretched canvas... this piece speaks of expanding manufacturing. Editor: That's interesting; I hadn’t considered the materials that way. Curator: Consider also what "brute force" signified during that time. Pils likely witnessed firsthand social unrest—the revolutions that swept through Europe, workers' uprisings, all fuelled by this shift from agrarian life to industry. Brute force, perhaps, isn’t just about physical violence but about this relentless machinery. Minerva, the goddess of wisdom and strategic warfare, rises against it. Editor: So, is Pils critiquing industrialization? Curator: Not necessarily. Pils received commissions from the Second Empire. The painting style—the romanticism, the allegory—shows how the dominant powers justified this shift. Notice how even the act of creating this image became entwined with the very societal changes it depicts. The making of the oil paint itself is implicated! Editor: It’s strange to think that the paint is also participating in the historical conflict the painting is portraying. Thanks for your insights. I’ll definitely be researching 19th century industrial production more thoroughly. Curator: Absolutely, paying attention to the production of materials adds layers to interpreting any artwork.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.