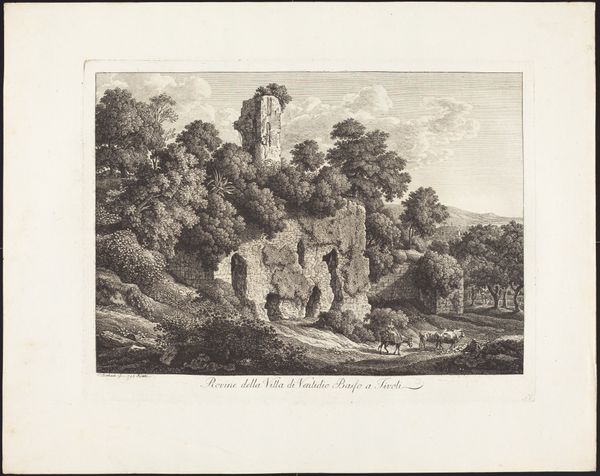

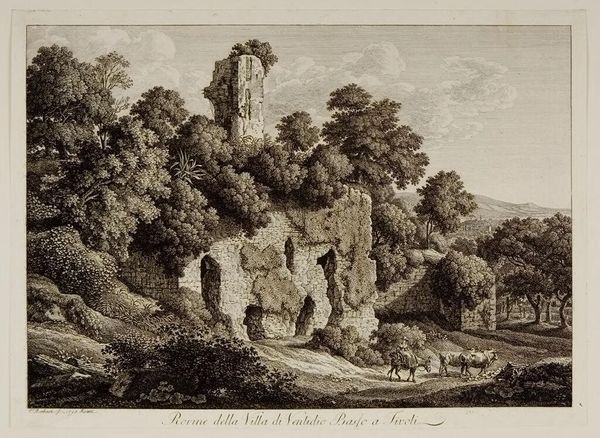

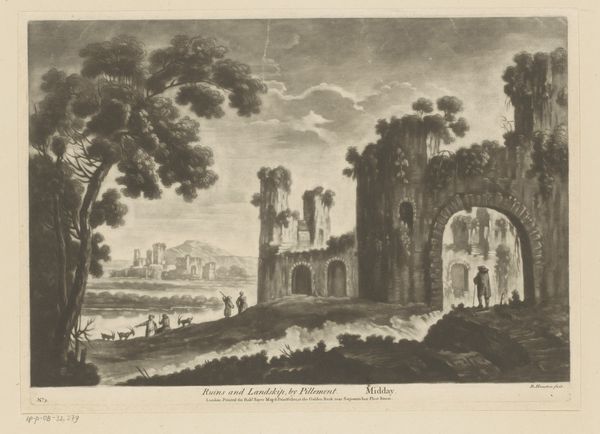

drawing, print, etching, paper

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

paper

Dimensions: 249 × 337 mm (image); 285 × 357 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Friedrich Wilhelm Gmelin’s etching, “Temple of the Serapide, Palestrina” made in 1793 offers a captivating glimpse into the past. Editor: The way the ruin sits within the landscape almost feels like a natural formation, blending seamlessly with the foliage and surrounding hills. It evokes a serene and reflective mood for me. Curator: Yes, Gmelin definitely emphasizes the harmonious relationship between nature and the decay of classical architecture. He does an excellent job to connect the dots between Neo-classicism and landscape traditions, even using etching in place of paint. It is one of many prints and drawings currently held at the Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: You know, the architectural elements, like the arches and the remnants of walls, feel less about the temple's original grandeur and more about the passage of time. See how nature reclaims them; trees growing atop the structure. It's as though Gmelin hints at a cyclical nature of civilizations, rising and falling. The whole composition really reflects on humanity's ephemeral existence against the backdrop of nature’s eternal rhythm. Curator: Absolutely, and Serapis himself, this composite Greco-Egyptian deity—his temple now overgrown—acts as a poignant symbol. The meticulous detail in the etching captures the rough texture of the stone, the play of light and shadow. What seems odd is how those details contrasts with the figures in the foreground: so small and easily dwarfed. Editor: Ah, right—those tiny human figures, almost like afterthoughts. Their presence, ironically, underscores our small part in the unfolding drama of time, memory and landscape, despite the human drive to create these ostentatious structures in their honor. I also noticed how that one cloud seems to break the otherwise flat sky! I wonder what Gmelin wanted to convey through its inclusion... Curator: Maybe the sublime? The idea of being overwhelmed by nature's grand scale was very romantic in that era, don't you think? It makes me ponder what kind of emotional resonance Gmelin sought from his viewers. Editor: Looking at it again, I wonder if, despite the melancholy of ruins, the lasting nature of symbols – temples, deities, art itself – continues to resonate across centuries and even empires, doesn't it?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.