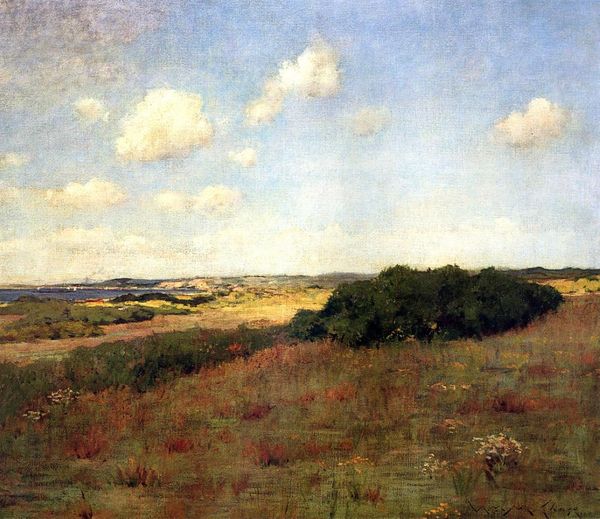

Dimensions: 66.04 x 91.44 cm

Copyright: Public domain

Curator: The expansive composition really captures the specific geography, and its attendant cultural history, don't you think? Editor: It definitely evokes a sense of vastness. The muted color palette gives it an almost melancholic feeling, as if observing the landscape through a wistful lens. Curator: We’re looking at William Merritt Chase’s “Landscape – A Shinnecock Vale,” painted in 1895. Chase spent considerable time at Shinnecock Hills on Long Island, where he mentored students, painting en plein air. It's worth noting, this location had previously been tribal land used for hunting, fishing, and gathering before colonial settlement, part of the displacement and forced labor so familiar. Editor: I am struck by the seemingly hurried application of the paint. I wonder what the materiality suggests about its social and economic context, given that Chase was instructing, essentially producing, alongside his students. Curator: Absolutely. You can see the influence of Impressionism here – capturing the transient effects of light and atmosphere through the medium. Consider the material properties of the paint, thick impasto in areas, giving a tactile quality to the foliage in the foreground. His process embodies the era, focusing on immediacy and observation as both pedagogy and artistry. Editor: Do you see in its muted color choices and slightly melancholy landscape perhaps an aestheticization of loss—the transformation of native lands into bourgeois leisure destinations? Or maybe I am projecting too much contemporary angst? Curator: Perhaps. But remember Chase wasn't unique. Many landscape artists romanticized places with troubled histories. Still, to think critically, we must situate this work, produced during the height of the Aesthetic movement, within the context of urbanization, industrialization, and Indigenous displacement. Editor: Looking closely, I am curious how much did his students contribute practically to this piece and others like it? How much collaboration versus demonstration was involved in Chase's landscape output? The labor question really jumps out for me. Curator: A vital question, indeed! One that invites consideration of these landscapes not just as aesthetic objects but also as products of collective work—a visual record imbued with social and political layers. Editor: It's easy to just admire the view, but there is clearly a lot more to consider here. Curator: Precisely. This conversation demonstrates that even serene landscapes can contain complex dialogues about history, labor, and place.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.