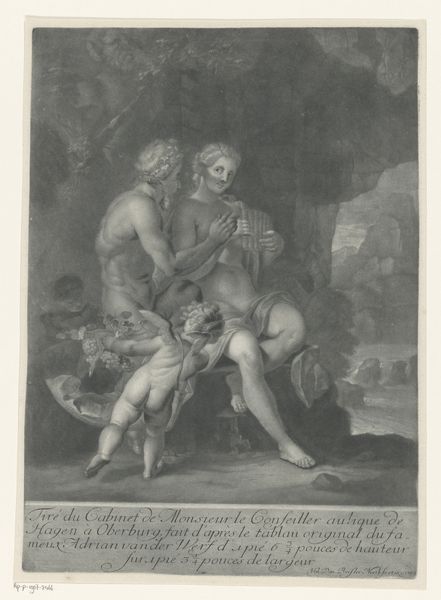

Dimensions: Image: 8 1/16 × 6 5/8 in. (20.5 × 16.8 cm) Sheet (Trimmed): 9 7/8 × 7 7/8 in. (25.1 × 20 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: The way the light falls in this engraving immediately draws you in. It feels secretive. Editor: Absolutely. Let's consider Jacques Bouillard's "Susanna at the Bath," made between 1781 and 1791. It's an engraving, after a drawing by Joseph Chari, and depicts a biblical scene. We see Susanna caught at a moment of private ablution. How do you interpret the composition? Curator: Well, beyond the play of light and shadow that create such a dramatic mood, the gaze of the elders spying on Susanna just above her shoulder is quite unsettling. It feels like an intrusion. Her vulnerability is palpable. In today's terms, we might call it a violation of privacy. Editor: The story of Susanna and the Elders has long been fodder for art, raising interesting questions about voyeurism, power, and female agency. Remember that visual imagery often serves those in power, so how do we situate this depiction of a nude woman within the broader social and cultural frameworks of the late 18th century? Was it meant to titillate? To moralize? To serve as a cautionary tale? Curator: Probably a bit of all three. I mean, her body is very deliberately presented. It’s hypersexualized by that male gaze embedded within the scene. She is devoid of agency; more like a stage for external judgement, wouldn't you agree? Editor: The interesting part is, from the art-historical point of view, is how this narrative became an occasion for exploring the nude female form within specific cultural boundaries. While the composition indeed emphasizes Susanna's vulnerability, let’s remember the prevailing artistic trends of the era. Representations like these offer clues about societal attitudes and the ways visual media perpetuates or even challenges accepted cultural standards. It all played a role in the sociopolitical discourse surrounding virtue, modesty, and the roles that women played in the society. Curator: It’s a disturbing, if visually alluring, reminder of how female bodies have historically been policed and surveilled, their privacy disregarded and their personhood diminished through art and societal structure. Editor: Exactly. It's fascinating to see how such a piece from the Metropolitan Museum can open dialogues connecting artistic practices to societal power structures that influence the art world and art consumption even to this day.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.