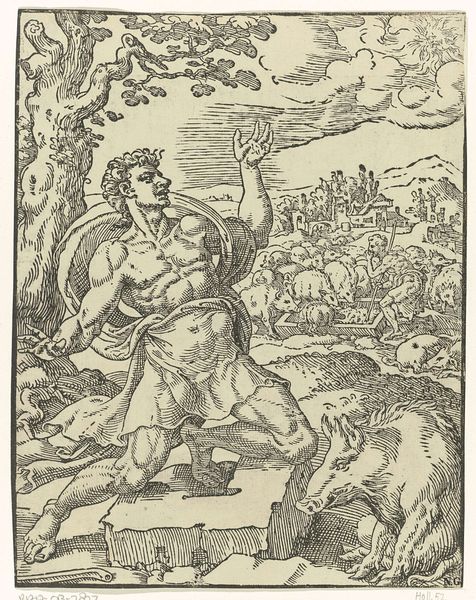

print, woodcut

#

narrative-art

# print

#

figuration

#

woodcut

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

Dimensions: height 100 mm, width 155 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Hans Schäufelein's woodcut, titled "Kaïn doodt Abel," dates from the late 15th to early 16th century. This print vividly depicts the biblical narrative of Cain slaying Abel. Editor: A visceral, dramatic piece! The stark contrast of the woodcut amplifies the brutality of the scene, wouldn’t you say? The sheer dynamism of Cain's pose—arm raised, weapon in hand—it creates a palpable sense of impending violence. Curator: Indeed. The image gains greater meaning when considered in the social context of the Northern Renaissance. Printmaking allowed for widespread dissemination of biblical stories, shaping religious understanding among a largely illiterate population. Schäufelein, working in Nuremberg, a hub of printing and humanism, helped to translate these pivotal stories to larger society. Editor: Looking at the figures, their bodies seem almost sculpted through light and shadow—an artistic trick enabled by the medium. The linear details give form and weight to both the victim and the aggressor, while also dramatizing the background's craggy rock and gnarled tree. Curator: The placement of this gruesome event amidst details of ordinary landscape draws a potent parallel between divine history and lived human experience. It is a reflection on the pervasive nature of sin, mirrored by the landscape surrounding them, accessible to all at the time through this medium. Editor: There’s an emotional complexity embedded here, in my reading of it. It transcends pure illustration; it invites the viewer to confront difficult truths about jealousy, anger, and the consequences of primal violence. The tension literally carved into the artwork, amplifies its narrative power. Curator: That power surely arises from how the woodcut served to bring critical moral and religious lessons out of cloistered elite discourse to wide audiences struggling to grasp enormous change during this time period. Editor: Ultimately, I would suggest it stands not only as a historical artifact, but as a testament to how formal construction and visual composition—here, within printmaking—can evoke strong human emotion.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.