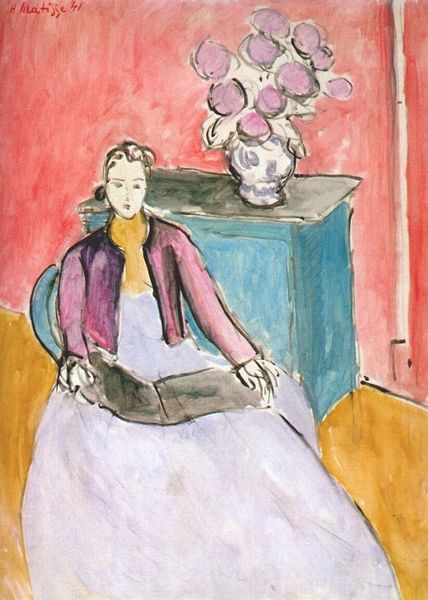

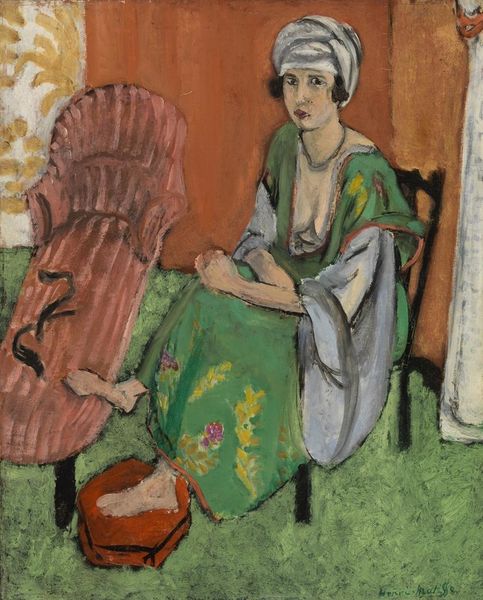

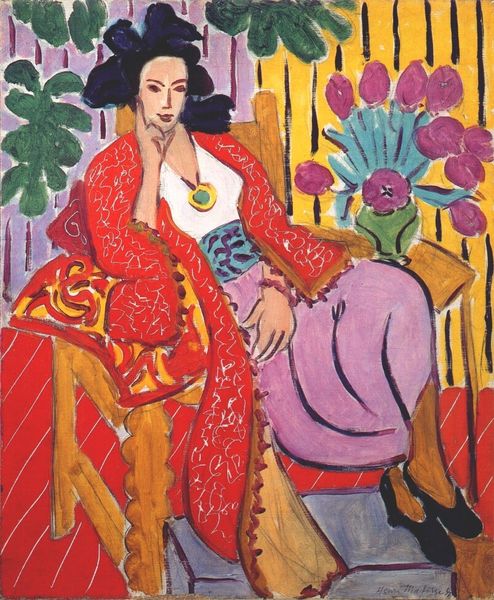

Copyright: Henri Matisse,Fair Use

Curator: Let’s turn our attention to Henri Matisse's 1937 watercolor, "Blue Dress in Ocher Armchair." Editor: What strikes me first is the overall stillness—the palette feels subdued, almost melancholic. It’s a quiet domestic space, yet there's something unsettling about the sitter's averted gaze and the flatness of the picture plane. Curator: It's fascinating how Matisse continuously reinterprets domestic interior. Consider that at this time leading up to the war, his work increasingly portrayed women in these controlled, interior spaces as reflections of beauty, calm and contemplation—perhaps a refuge from the anxieties brewing outside the canvas. Editor: A refuge, or a gilded cage? Look at how the woman’s body merges with the armchair and background. It echoes those very conversations swirling around women’s confinement during that era, their expected roles, the limits placed on their visibility and mobility. The artist places the sitter inside a decorative prison of his own design, literally hemmed in by rigid rectilinear blocks, with flat color which lacks conventional depth. Curator: It’s interesting that you note her near-integration with the domestic objects, since this was a technique Matisse would pursue until his death, that sought harmony through what he termed ‘condensation.’ By obscuring spatial depth he emphasizes instead, the decorative patterning in the space, creating pictorial unity, with this effect especially reinforced by the flatness of watercolor. Editor: Condensation perhaps also to the female role in life? Look at the treatment of women, from a critical feminist perspective, as both aesthetic ideal and as property. One cannot separate artistic intention from a gendered reading in such contexts; she is being both captured and made captive. It reflects an intellectual anxiety related to cultural expectations. Curator: Your reading highlights the tension between personal expression and prevailing social attitudes. I am keen to understand how our present socio-political awareness actively engages and, perhaps challenges, the traditional appreciation of intimate, interior works produced at the historical moment between world wars. Editor: Precisely. This painting gives us license to question not only the image, but the institution that frames and presents it. Whose gaze are we adopting, and whose stories are we prioritizing within these gallery walls?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.