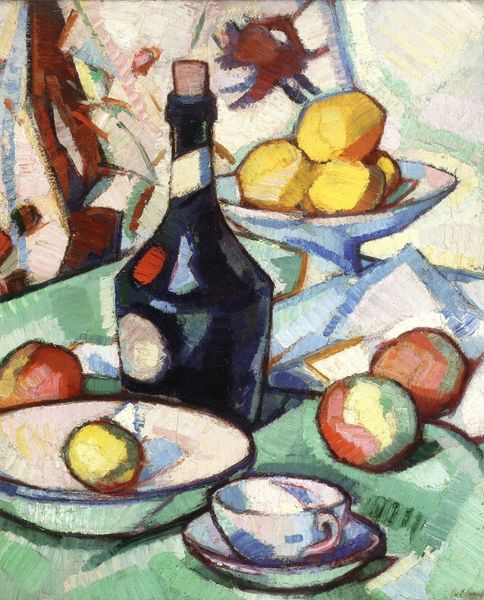

Copyright: Public domain

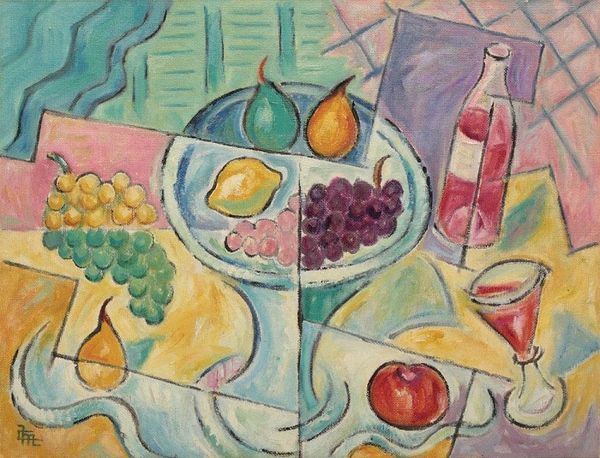

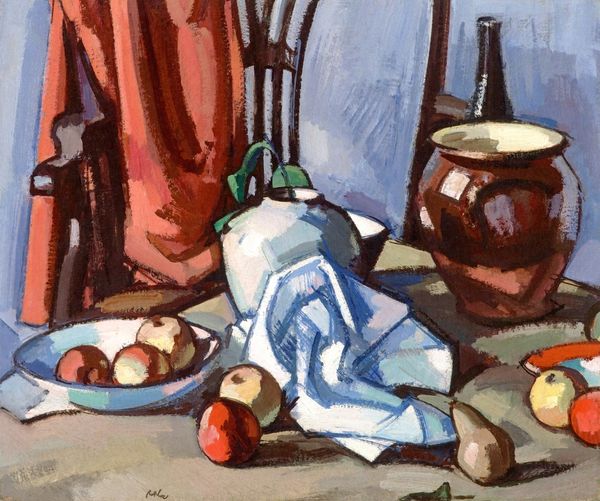

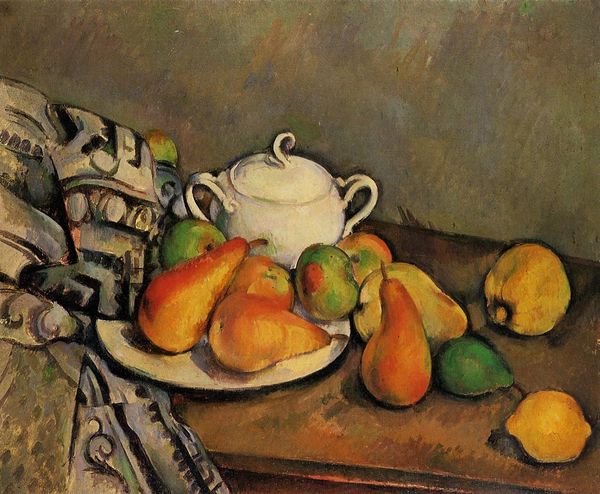

Curator: Standing before us is Samuel Peploe’s "Still Life" from 1913, currently residing here at the Scottish National Gallery. What’s your immediate take? Editor: Angular. It strikes me as aggressively cheerful, like a forced smile. All those geometric shards of color – are they really inviting, or are they a little… pointy? Curator: That tension is key, I think. Fauvism, right? Exploding the expected color palettes, liberating emotion onto the canvas. Look how he’s taken these everyday objects – a pitcher, a wine bottle, some fruit – and elevated them through pure, almost violent color. Editor: Violent is the right word. I am fixated on the production: all that paint! The sheer materiality of it screams at you. What sort of brushstrokes create such disjointed segments? It’s not simply representation, it’s… assertion. This wasn’t about depicting reality, but about crafting a new one. Curator: Exactly. The composition itself rejects traditional notions of perspective and form, pushing the boundaries of modernism. It feels very… Scottish, somehow. A kind of stubbornness married with raw beauty. You know, Peploe was deeply influenced by his travels to France. Editor: Ah, France. That probably explains the wine bottle! But, truthfully, what kind of labor practices and social interactions framed the work in Scotland? Let us remember this was only shortly before World War One... Were the materials locally sourced? What did that even mean back then? And whom was art truly available to, when we're reckoning the relationship of labor and class. Curator: Hmm, valid. But, forgetting all that for a moment, does it resonate on any level? Any whispers of the intuitive experience within all that pigment? I have seen, looking at this for some time now, that everything trembles here, even the flower. Editor: I am very moved, yet there’s something uneasy about the still life genre, to begin with. These items brought together by forces unknown! The social economy of leisure, luxury, the things available for artistic expression... This artwork forces one to contemplate its moment of construction. The still lives and all its artifice… I now feel the violence, in looking. Curator: That's a powerful point. Perhaps that disquiet is what keeps it so engaging, all these years later.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.