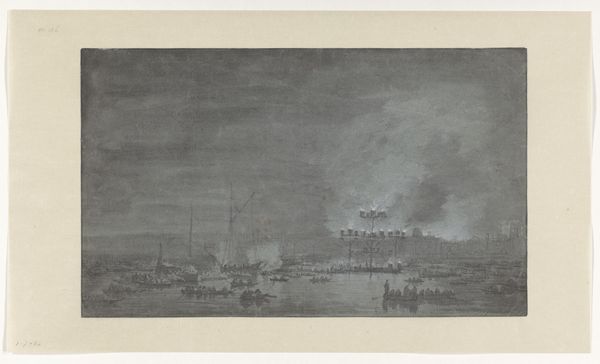

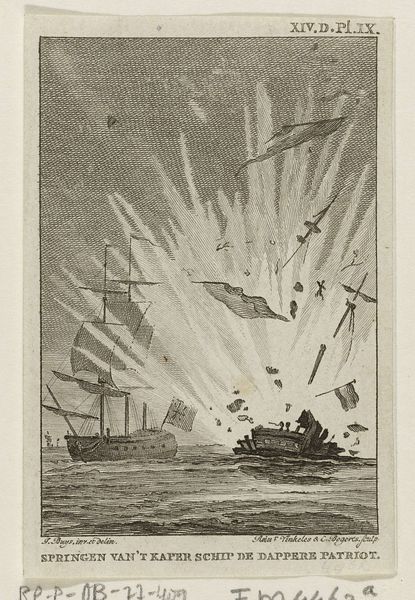

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

# print

#

romanticism

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 389 mm, width 480 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

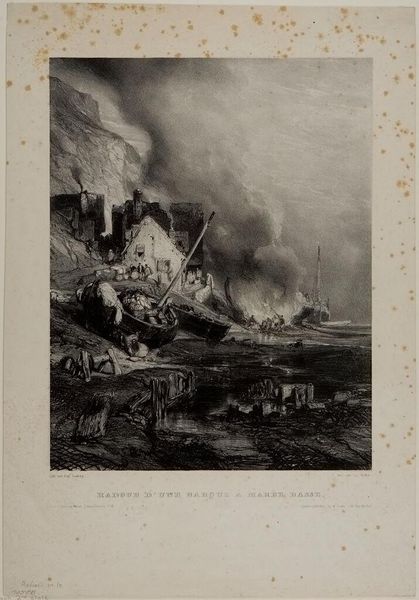

Curator: Looking at this engraving, my first impression is dominated by a sense of chaotic energy and destructive force. Editor: That’s exactly the sentiment Franҫois Magneé aimed to capture in "The Gunboat Exploding of Jan van Speijk, 1831," now hanging here at the Rijksmuseum. He made this print, an engraving actually, of the heroic yet controversial death of Jan van Speijk. Curator: Controversial indeed. An explosive end to his life, dramatically portrayed here through jagged shards and plumes of smoke. I see it echoing other Romantic depictions of disaster, like shipwrecks or battles consumed by chaos. The etching captures a moment of extreme nationalistic fervor, almost feverish, doesn't it? Editor: Absolutely, there is that feverish aspect! The event itself quickly became a symbol in the young Kingdom of the Netherlands – of unwavering patriotism and sacrifice against the backdrop of Belgian independence aspirations. It was the age of nascent nation-states needing iconic martyrs, someone to crystallize their collective identity around. Curator: Precisely. And even in this grayscale image, that collective identity is vividly captured. The stark contrast suggests to me a struggle, the bright burst against the subdued greys mirroring the tension between patriotic glory and violent demise. I wonder about the immediate emotional effect it had; whether its impact rested on immediate horror or, perhaps more subtly, on a gradual heroic romanticizing of van Speijk's final act. Editor: Both, I think. But let’s consider its circulation. Engravings were mass-produced images; think proto-internet memes. They appeared in homes, in taverns... they quickly normalized the image, reinforcing state-sanctioned narratives about duty. It’s this distribution that helped cement the political meaning for an entire generation. Curator: Ah yes. Its ubiquity almost transcends the specific moment, it becomes a timeless expression of self-sacrifice, repurposed for diverse anxieties across the following decades, almost devoid of specific narrative constraints. Editor: In many ways, the print is an artifact demonstrating how visual propaganda functions, distilling complex socio-political events down into easily digestible heroic narratives. Curator: Thank you. Looking back at Magneé’s work with this in mind gives me so much to reconsider about both image and its complex reception history. Editor: And for me, that visual reminder of just how strategically chosen are symbols for forging communal consciousness is profoundly significant.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.