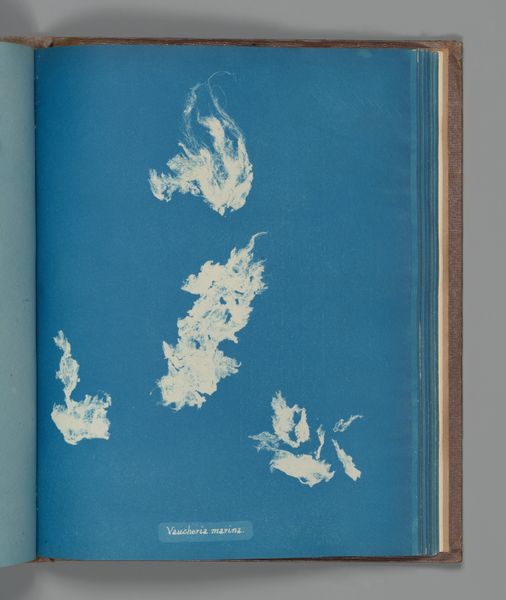

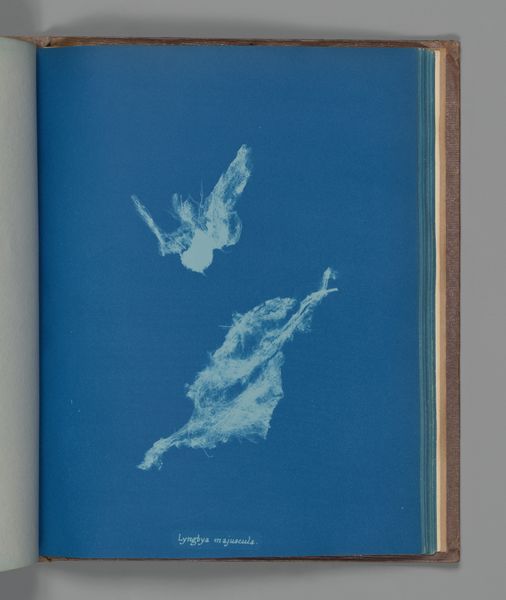

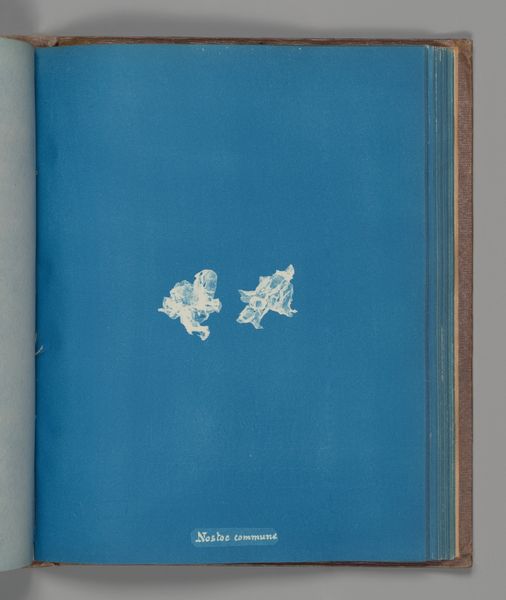

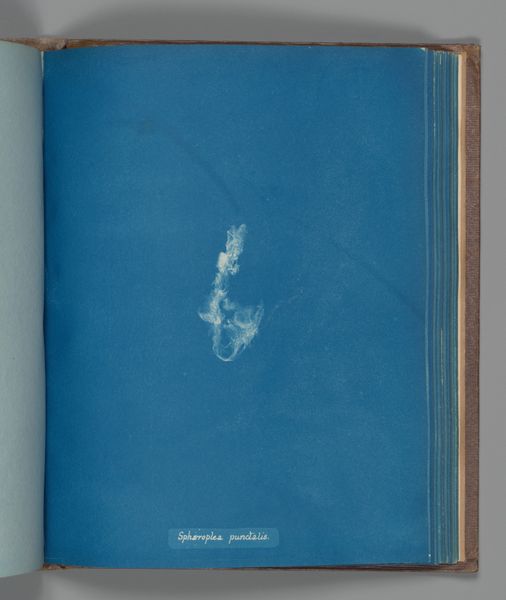

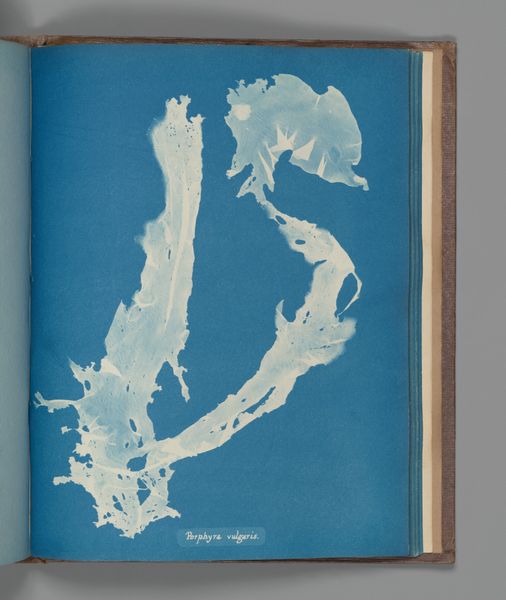

print, cyanotype, photography

# print

#

cyanotype

#

photography

#

realism

Dimensions: Image: 25.3 x 20 cm (9 15/16 x 7 7/8 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

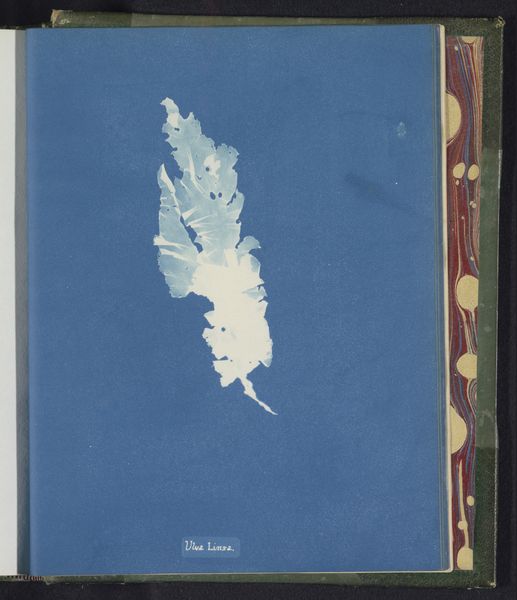

Curator: Looking at Anna Atkins's cyanotype, "Ulva Linza," created between 1851 and 1855, one can immediately recognize the innovative intersection of science and art. It’s currently housed here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: Gosh, the almost electric blue is so arresting! It gives the seaweed, that Ulva Linza, this spectral, ethereal quality. I’m instantly drawn to it. Curator: The cyanotype process itself, using iron salts and sunlight to create these distinctive blue prints, was a relatively new technology at the time. Atkins’s work became significant as it’s one of the earliest examples of photography used for scientific documentation. I always find that context important in understanding her pioneering vision. Editor: Exactly. It’s so much more than just a pretty picture of seaweed. You get a sense of this quest for knowledge, this urge to categorize and understand the natural world. And, dare I say, I feel a melancholic quality about it – it’s a ghost of a plant, beautifully preserved on blue. What does that tell us? Curator: That melancholy, I believe, speaks to the inherent ephemerality of nature itself. The detailed realism in rendering the alga alongside its preservation through technological means offers a commentary on nature, science, and mortality that touches on very resonant points. It underscores ideas about scientific positivism within Victorian social values too. Editor: So much to consider! And that the cyanotype feels so timeless... Do you think Atkins was conscious of these different angles or simply wanted to document it beautifully? Curator: It’s precisely the layering of intentions and consequences, of artistic vision and scientific impulse, that make "Ulva Linza" such a compelling object for contemporary re-evaluation. Editor: I agree. After spending this time looking closely, I find a new fascination at the cross section of art, nature, and innovation... The print is like a little jewel, isn’t it? Curator: It absolutely is. It provides a crucial intersection of aesthetic wonder, scientific inquiry, and Victorian history, continuing to echo meaningfully for audiences today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.