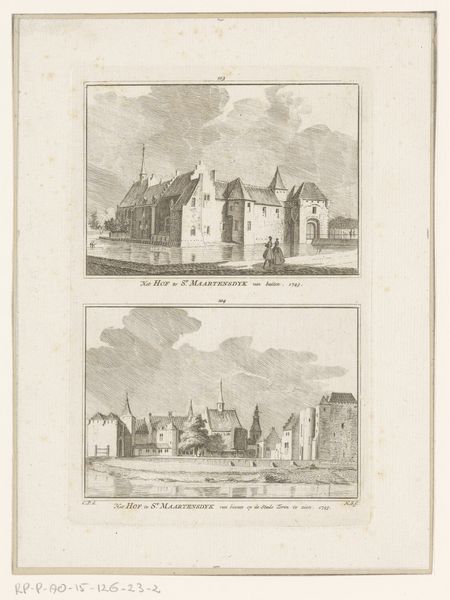

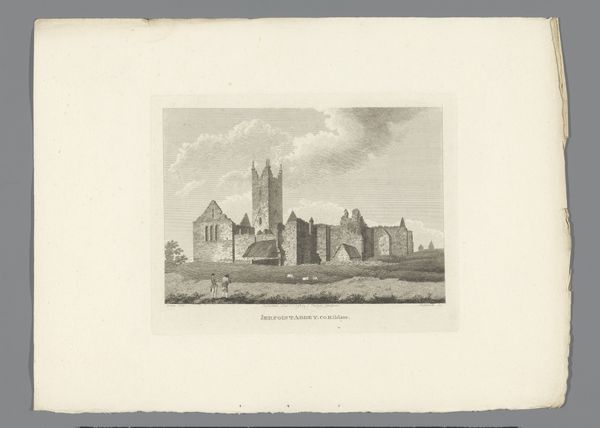

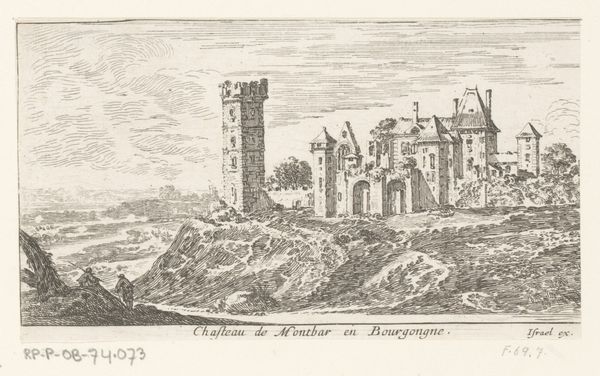

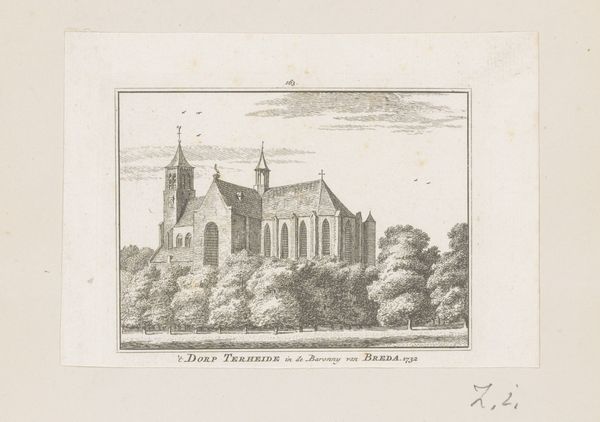

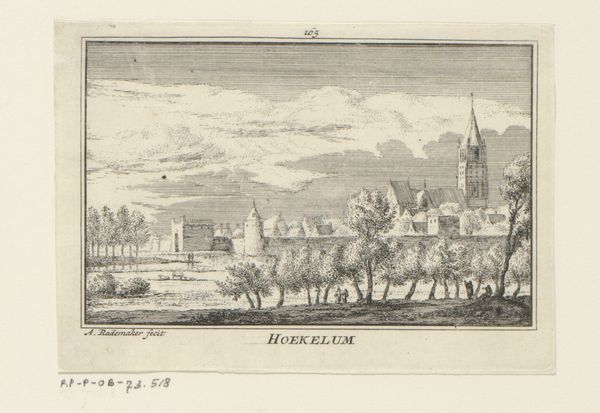

Gezicht op de ruïne van het klooster Koningsveld, 1573 1727 - 1733

0:00

0:00

abrahamrademaker

Rijksmuseum

drawing, print, etching, ink, pen, architecture

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

pen sketch

#

etching

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

ink

#

pen

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 80 mm, width 115 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

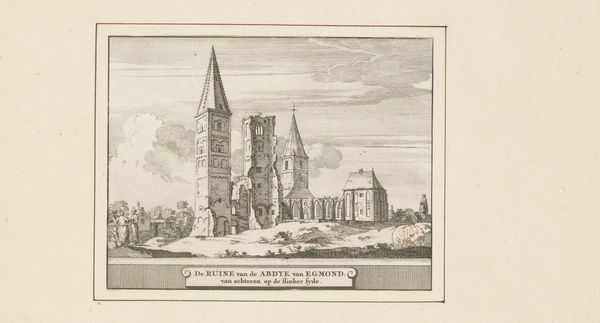

Editor: So, here we have Abraham Rademaker's "View of the Ruins of the Koningsveld Abbey, 1573," created between 1727 and 1733 using pen, ink, and etching. It feels so stark, so much about loss and the passage of time. What do you see in this piece? Curator: I see more than just loss. This work allows us to think about the power dynamics inherent in iconoclasm and religious conflict. The ruined abbey stands as a testament to the struggle between differing ideologies and their impact on physical spaces. Think about the Reformation; what does destroying religious spaces achieve? Editor: It's like erasing history, isn't it? Or rewriting it through destruction? Curator: Exactly! And Rademaker, in depicting these ruins almost two centuries later, is participating in a dialogue about memory, power, and the enduring scars of religious conflict. The choice of etching, with its ability to render fine detail, invites us to meticulously examine the consequences of such actions. Who benefits from the destruction and who suffers? Consider also, how does the surrounding landscape – that somewhat indifferent nature – interact with human endeavor? Editor: I hadn't considered the role of the landscape, but that really resonates. It makes the human conflict seem almost insignificant against the backdrop of time. Curator: Precisely. It's an intersectional story, woven with threads of religion, politics, and social change, challenging us to contemplate the long-term impacts of intolerance and violence. This image documents physical erasure, but also prompts thinking about cultural resilience and the enduring human need for meaning and belonging. Editor: I see the piece in a completely new light now. Thanks for highlighting the socio-political dimension, the bigger historical context. Curator: My pleasure. Art provides space to question existing historical records and contemplate complex political contexts. It really goes to show, history isn't ever static!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.