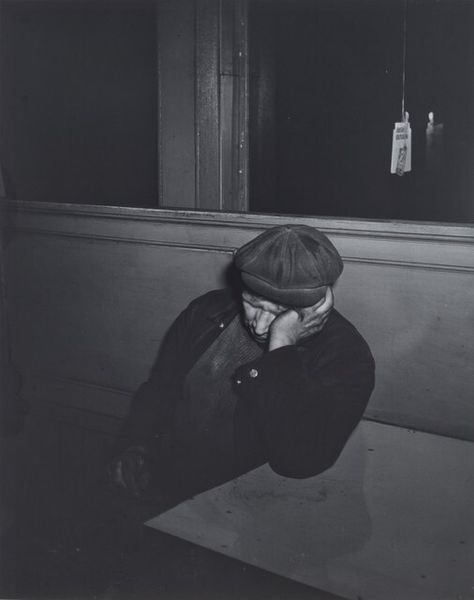

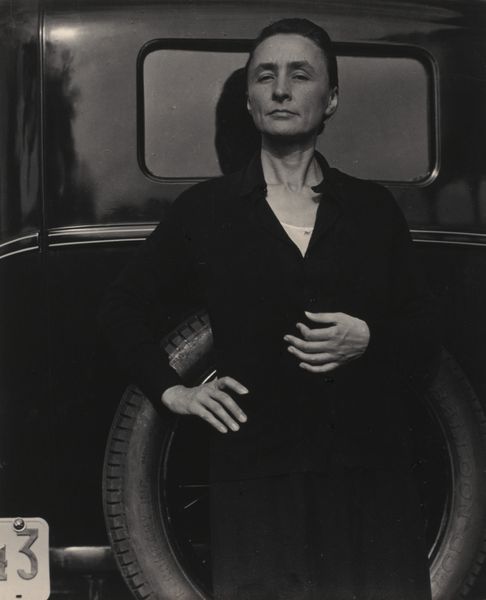

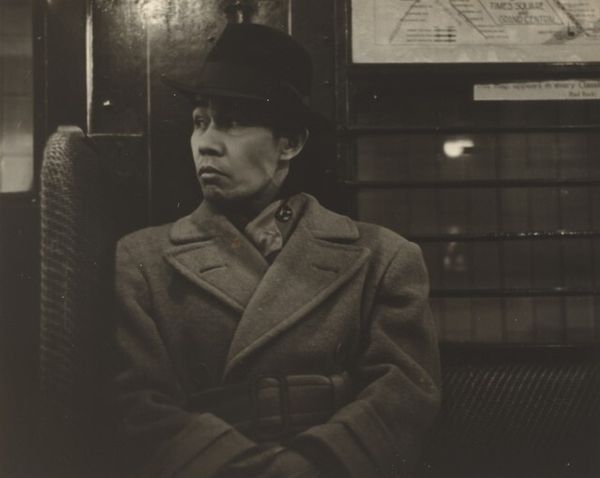

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

black and white photography

#

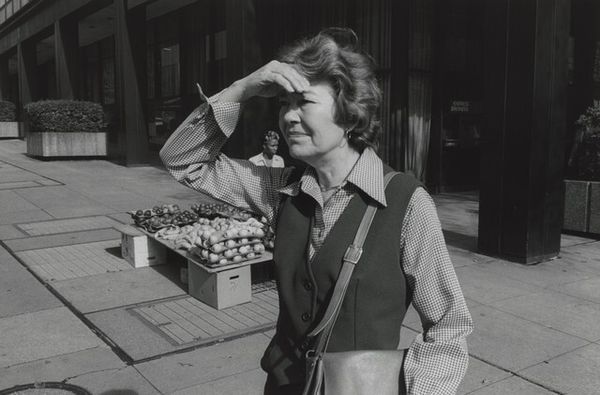

street-photography

#

photography

#

black and white

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

monochrome photography

#

monochrome

#

modernism

Dimensions: image/sheet: 21.27 × 14.5 cm (8 3/8 × 5 11/16 in.) mount: 35.56 × 27.94 cm (14 × 11 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

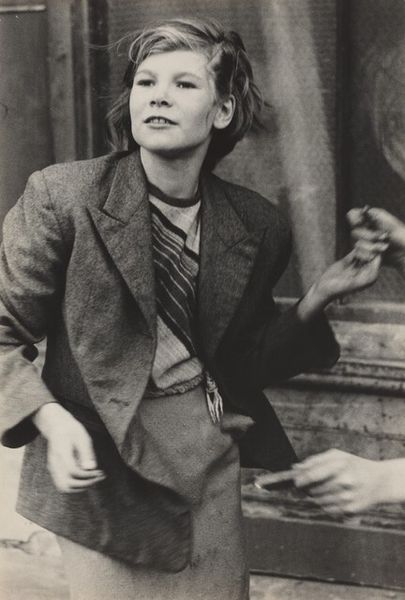

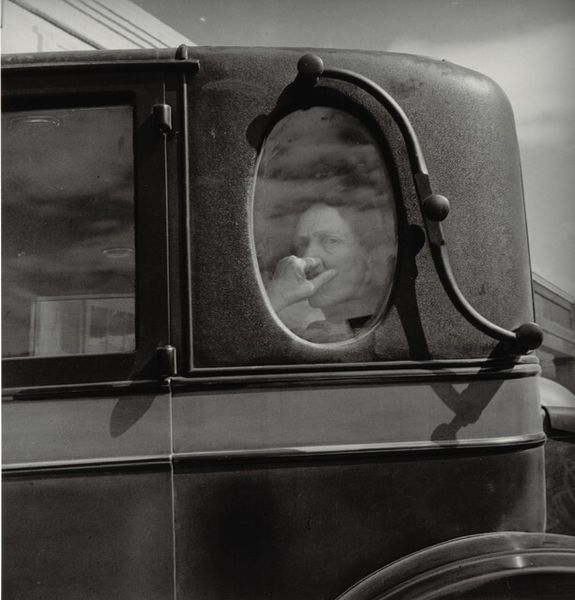

Editor: This evocative photograph, titled "London," was created by Eva Rubinstein in 1969 using the gelatin-silver print technique. The image of a young person looking out a train window has a certain melancholy to it. How do you interpret this work, considering its historical context? Curator: That melancholy feel is interesting, and I think you’re right to pick up on it. Considering the photo was taken in 1969, we need to look at what was happening socially. Britain was in the midst of social upheaval – shifts in class, youth culture, and anxieties about national identity. The figure's fixed stare, the train, the setting, invite contemplation about movement and displacement. Do you think that these elements contribute to the feeling that the boy seems almost trapped or confined within this "London"? Editor: Definitely. The window frame acts as a barrier, almost like he’s in a box. And the heavy shadows add to that enclosed feeling. Do you think the fact that it's black and white photography plays a role in how we perceive it, versus if it were in colour? Curator: Absolutely. The monochrome strips away any distractions, leaving us to focus on the emotional content and the subject's state. Black and white photography in that era was often seen as more “serious,” tied to documentary photography and photojournalism that addressed social realities. It adds a layer of gravitas to the boy’s gaze. But there is always a risk to imbue work from a certain era to mean one singular thing, do you think we could go too far with this and miss a point? Editor: That's a good point. Maybe it’s also just a kid on a train, looking out the window! Still, understanding the social context gives the image another layer. It’s given me much to think about! Curator: Precisely. Analyzing through a historical lens helps us see how a seemingly simple image is loaded with broader cultural and social meaning, and perhaps its deeper purpose for existing as a work of art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.