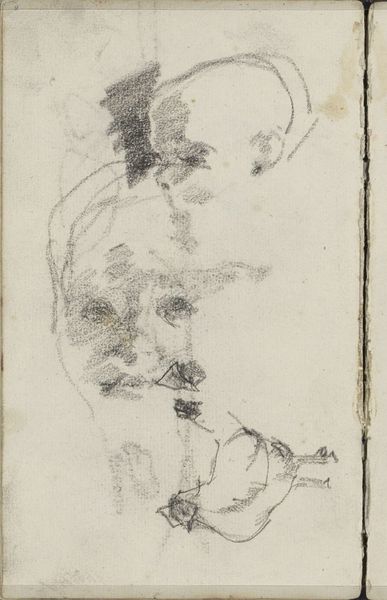

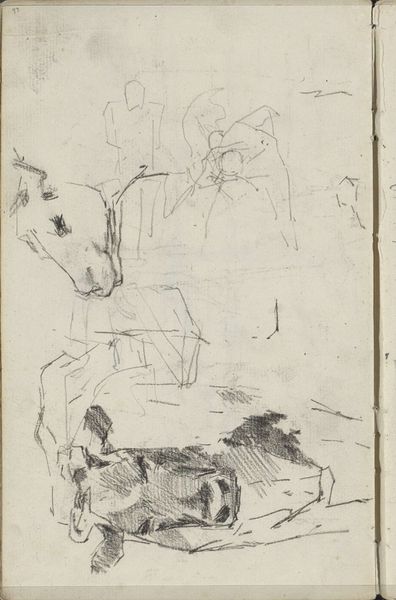

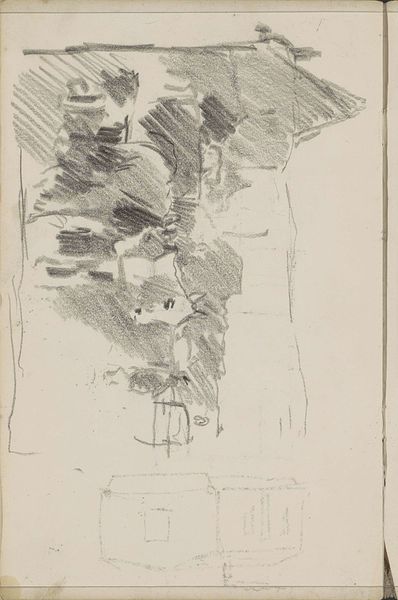

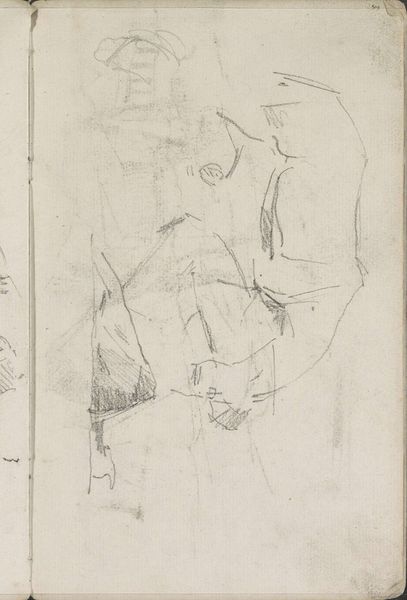

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

amateur sketch

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

#

impressionism

#

sketch book

#

incomplete sketchy

#

personal sketchbook

#

sketchwork

#

detailed observational sketch

#

pencil

#

sketchbook drawing

#

sketchbook art

#

profile

#

realism

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is "Mannenhoofd, in profiel," or "Head of a Man, in Profile," by George Hendrik Breitner, from around 1884 to 1886. It's a pencil drawing, and it has a very raw, almost unfinished quality. What strikes me most is its directness – it feels like a quick study. What do you see in this piece? Curator: I see an engagement with the materiality of drawing itself. The "unfinished quality" isn't a failing but a demonstration of process. Look at the toned paper—its cost, its availability within Breitner’s social and economic sphere. Consider the implications of sketching in pencil during that period: What statement is Breitner making? Is he showing you labor or access to labor? What does the use of simple and relatively available media communicate, in comparison with traditional methods used in formal portraits? Editor: So, you’re saying that Breitner’s choice of materials—pencil on toned paper—is deliberate and tells us something about the context of its creation and possibly his values as an artist? Is it also indicative of social and artistic trends from that period? Curator: Precisely. It's a conscious decision that affects the very consumption and understanding of the artwork. Breitner positions himself apart from an aristocratic way of thinking about the artist’s practice. He may challenge established notions of artistry, craft, and labor by revealing process and challenging hierarchical methods. What implications would this type of presentation suggest to audiences of the time? Editor: It suggests maybe that art is more accessible, less precious, perhaps even challenging the elite by presenting the work in such raw terms. I never thought about how much a simple pencil could reveal! Curator: Absolutely. Materiality informs meaning. Even the choice to depict a ‘head in profile,’ rather than a formal portrait sitting tells us about its purpose and intended audience. What do you think this says about its worth or value, when contrasted against the labour that produces formal portraits commissioned by the wealthy? Editor: That really reframes how I see this drawing. I was focused on the image itself, not the significance of the pencil and paper that were employed, or their availability relative to materials used when portraits were formally commissioned. Curator: Exactly. Thinking materially can transform our experience with art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.