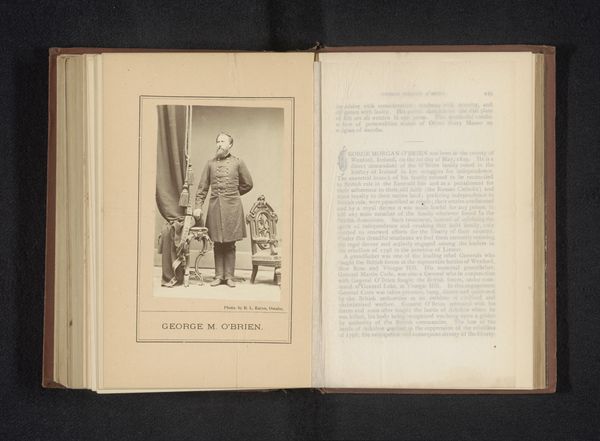

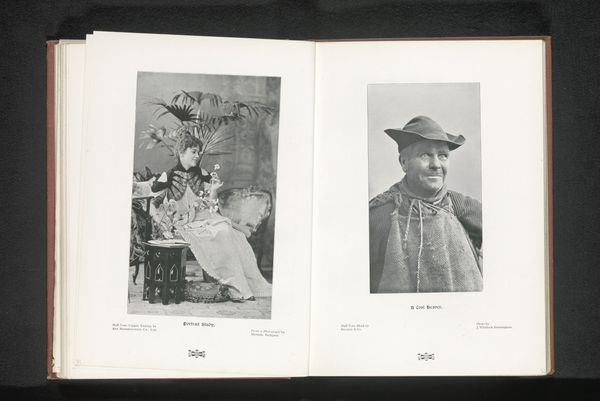

Portret van Antonie Fiat, Portret van Tagliabue, De paasmis in de Xishiku-kerk in 1895 en Portret van de zevende Prins, vader van de Keizer before 1897

0:00

0:00

print, photography

#

portrait

# print

#

asian-art

#

photography

#

coloured pencil

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 234 mm, width 159 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

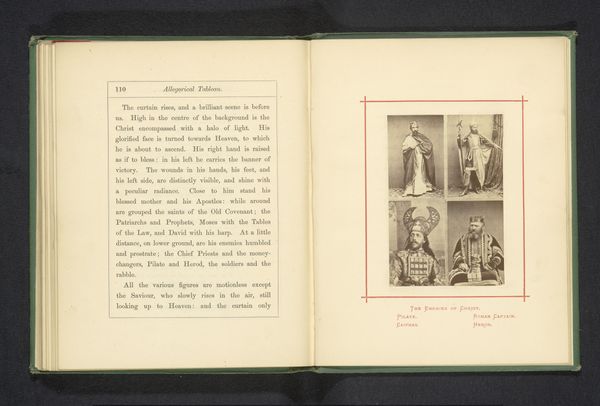

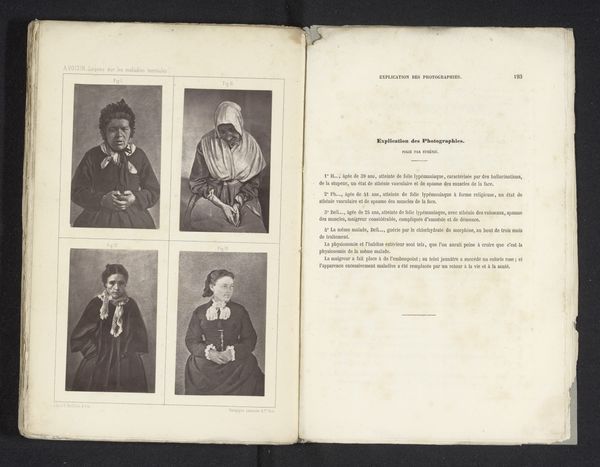

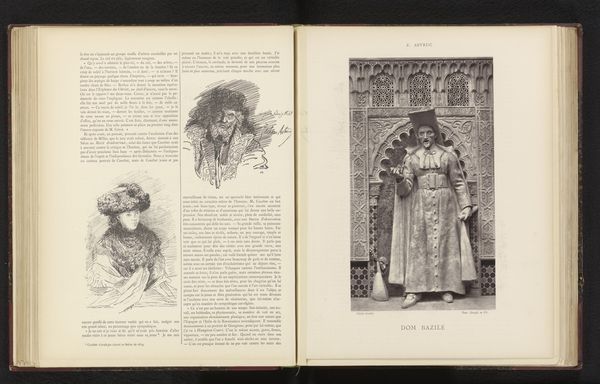

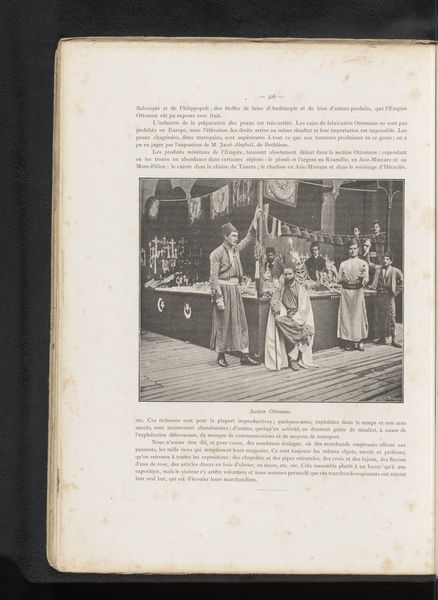

Curator: This composite print, likely predating 1897, presents a quartet of images including portraits and an interior scene within China. Its construction alone suggests a deliberate assembly, defying singular interpretation. Editor: My initial impression is of stark contrasts – light and shadow interplay across the portraits, yet there’s a certain formality, even a rigidity. The lower two images give a better sense of the everyday experience: the Easter Mass image feels vibrant in its architectural details and the seated man radiates authority. Curator: Looking at this collection from a materialist perspective, the reproductive nature of the prints themselves democratized these images. The photographic process allows widespread distribution; consider its accessibility. What did this circulation mean for understandings of faith, authority, or the Chinese state for the Western world at the time? Editor: It speaks to the dynamics of power inherent in representation. Whose gaze is privileged? The composition—juxtaposing religious figures with a royal one—seems to reinforce the orientalist narrative: religion and hierarchy go together. Notice the portraits and church are tightly framed while the Asian man occupies the largest and the most adorned space in the image! It raises complex issues about cultural appropriation. Curator: Right. Who held power and authority? There are many complex factors. If we look at the materials involved in printmaking and photography and how they are dispersed we must look into accessibility and distribution – which is so revealing, because each medium tells a specific part of that story! Consider the church interior shot. The detail evident within—presumably shot with photographic technologies developed only recently—demanded significant financial capital which implies specific interests who were behind it. Editor: Absolutely. By looking at it from the colonial gaze, however, and further by engaging in decolonial perspectives, it becomes less about art and more of visual culture in social life, how social institutions and knowledge itself can get weaponized, reinforcing asymmetries in a way that is almost banal because it gets normalized over time. This has shaped perception and understanding that carries to present! Curator: Thank you for opening that line of reasoning, this exchange has greatly deepened my perspective of these otherwise very isolated images! Editor: Me too, this image has many things to teach us about history!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.