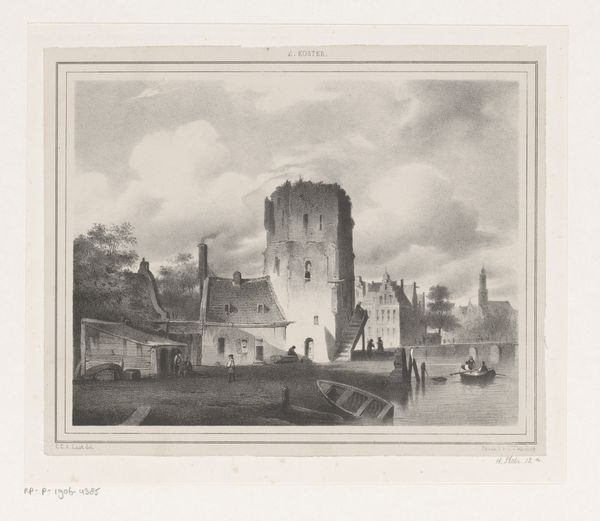

print, etching, engraving

#

medieval

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

etching

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 97 mm, width 143 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Ah, this etching has a distinct moodiness to it. I immediately think of crumbling empires and gothic romances. What's your take on it? Editor: It certainly evokes a sense of bygone eras! We’re looking at “Landschap met een ruïne in het water,” or Landscape with a Ruin in the Water, attributed to Isaac Weissenbruch, although its dating is somewhat broad, falling somewhere between 1836 and 1912. It resides here at the Rijksmuseum. Curator: You know, the lines have this…fragile beauty, like seeing something precious about to fade. It’s beautifully balanced but slightly sad, isn't it? Editor: Precisely. Weissenbruch, I think, presents us with more than just a pretty scene. Etchings like this gained popularity partly from the burgeoning sense of national identity that fueled romanticism—revisiting historical locations like the ruined castle could act as an important symbolic assertion of shared identity or legacy, of reflecting upon a romanticized vision of a collective past. Curator: You can almost feel the weight of all that history resting on those walls. The way he’s worked with light and shadow is really gorgeous, wouldn't you agree? Like memories in the act of solidifying, before dissolving all over again… Editor: Absolutely! The medium is also a critical lens for engaging with it, it’s just that etching and engraving techniques were used more broadly to reproduce imagery that aligned to popular concepts or trends across art, but they were also connected more closely to wider printing and publishing networks – it’s about mass communication too. Curator: Right. One often assumes landscape art deals with only natural scenes but that the architecture feels equally elemental to the composition, as much part of the world. I find myself inventing narratives here… what do you make of it, though? As a cultural signifier? Editor: I think that is its primary significance here, especially if you consider the sociopolitical context – Dutch history being reshaped by its relationship to industry, modernity, the legacies of colonialism – it’s an invitation to confront the past and present within this specific moment. The ruin, then, becomes a touchstone, and perhaps Weissenbruch might invite you to grapple with a future of collective action in solidarity… Curator: It does pose a sort of challenge. I feel called upon to imagine those futures within my own terms of self-definition, too. A very potent ruin, all told. Editor: Indeed! And thinking about this work in that context really brings out some hidden dimensions within a rather deceptively straightforward work of art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.