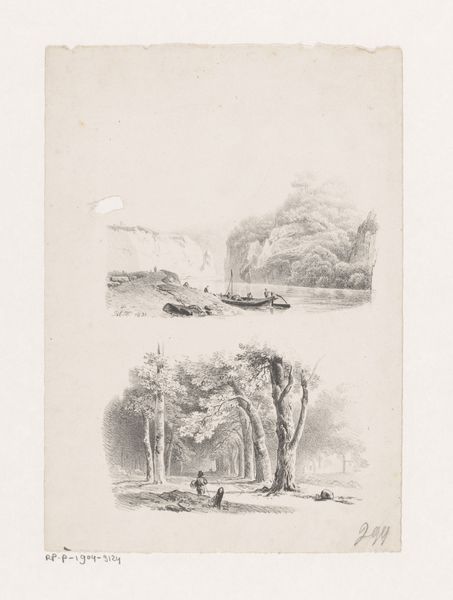

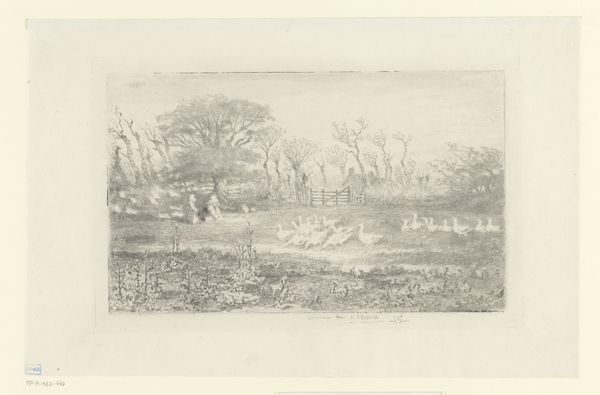

drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

landscape

#

form

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

line

#

northern-renaissance

#

realism

Dimensions: height 310 mm, width 483 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is Barend Cornelis Koekkoek's "Winter Landscape with Wood Cutters," dating from between 1820 and 1833, a pencil drawing currently residing at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My initial reaction is quiet solemnity. The starkness of the winter scene, the muted tones, it speaks of survival, and perhaps even isolation. The labor is right there, exposed. Curator: Indeed. Koekkoek's work often participates in an idealised version of a past rooted in the northern-renaissance aesthetic, imbuing landscapes with moral weight related to its laboring individuals. Consider how the diminutive figures contribute to a feeling of humanity working, but also at the mercy of, the vast, untamed landscape. The lone figures, cutting wood, can be read as symbolic of societal structure and human's place within it. The forest, a source of sustenance and peril. Editor: And what of those romantic overtones? The Romantic era fixated on nature's sublime power, didn’t it? But here, that sublimity seems tempered by realism. It’s less about awe and more about... what exactly? Everyday toil, maybe? This landscape, I think, offers a meditation on class. We are seeing workers trying to subsist. I also cannot help but think about how this piece was created right before the start of industrialized methods that were already gaining traction at this time, leading to so much land clearances and new means for labor, with new social standards to adapt to and against, simultaneously. Curator: It's a potent intersection. There’s a tension between the romantic idealization of the landscape and the raw reality of life it depicts. Koekkoek likely intentionally positioned the rural laborer within that socio-economic context, creating an idealized relationship with the earth even as urban-industrial landscapes changed it—and those worker’s lives--forever. Also, it’s worth pointing out how, even in this "realistic" scene, the very carefully chosen placement of elements suggests a harmony not always mirrored in lived experiences. The composition acts as both social commentary and carefully constructed idealism. Editor: So it functions as a bridge, reflecting backwards towards a more "pure" engagement, but anticipating those changes in landscape and labor that would radically alter human relationship in space and place? Curator: Precisely! Editor: It’s always striking how even seemingly straightforward landscapes like this can be so deeply layered with socio-political significance when we start digging into their historical context and intent. Curator: And on the ongoing importance of questioning the power structures present within depictions of our relationships to nature, as relevant now as when it was crafted.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.