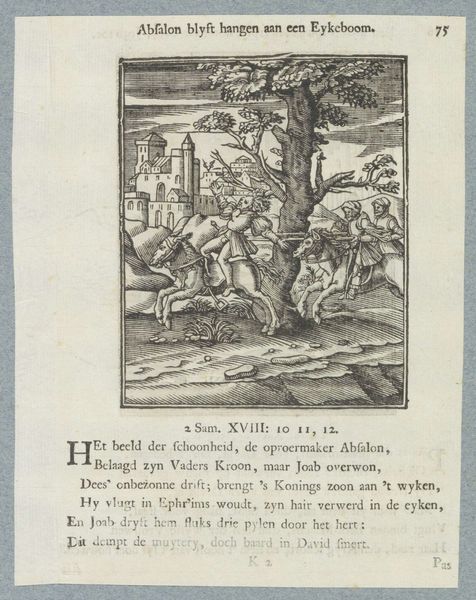

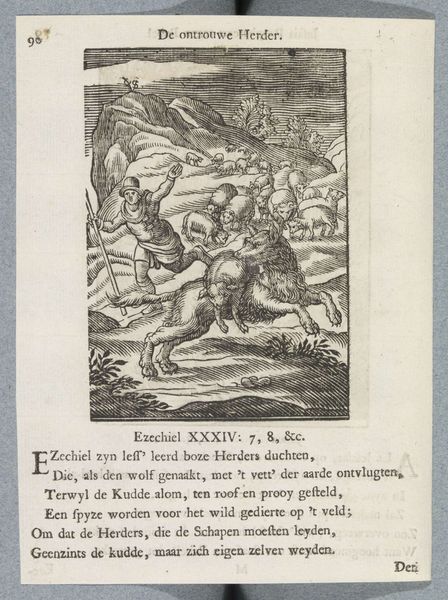

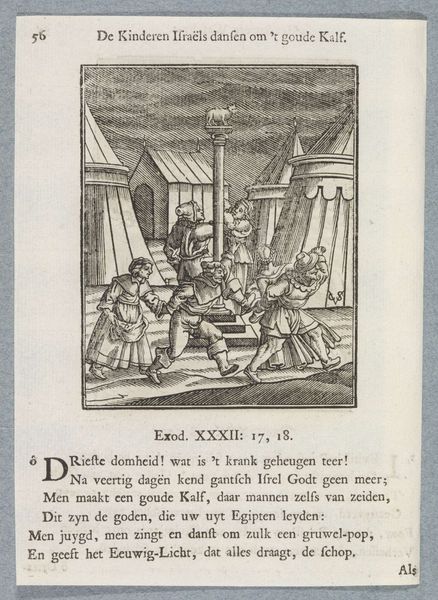

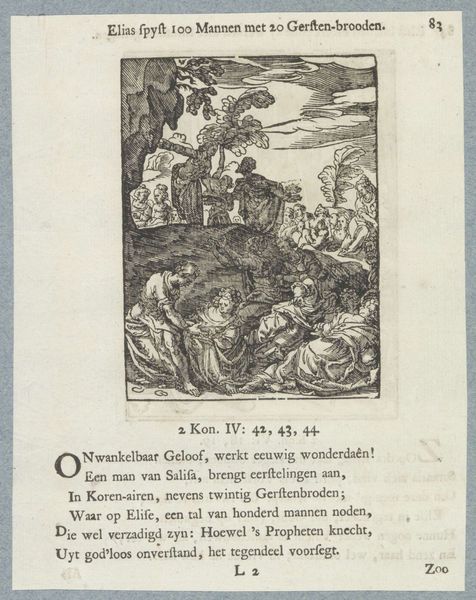

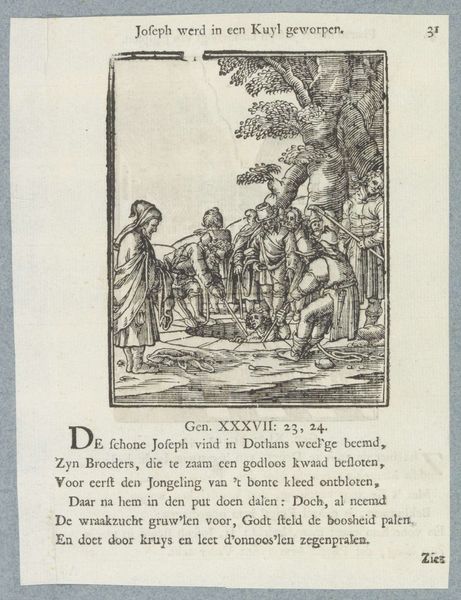

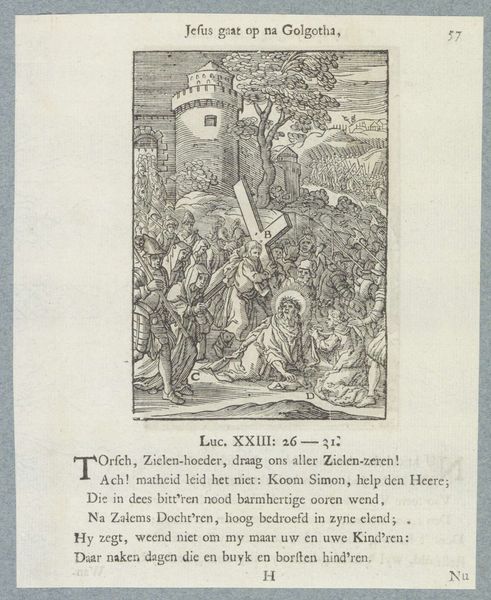

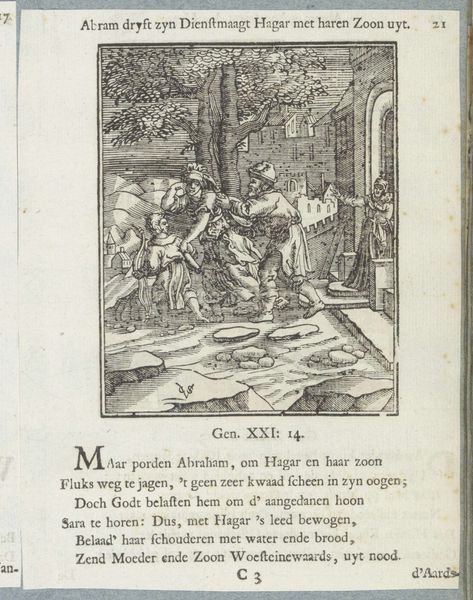

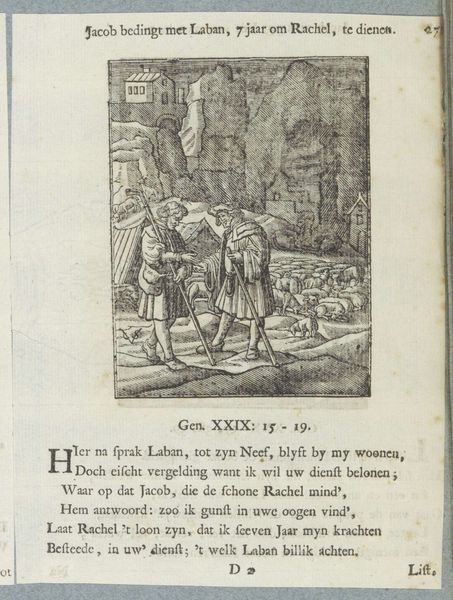

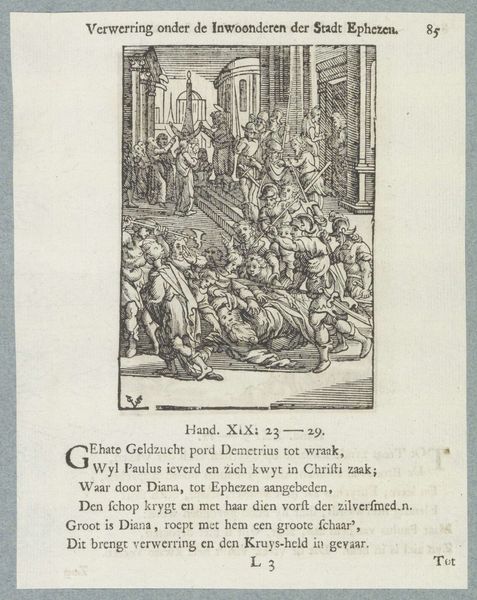

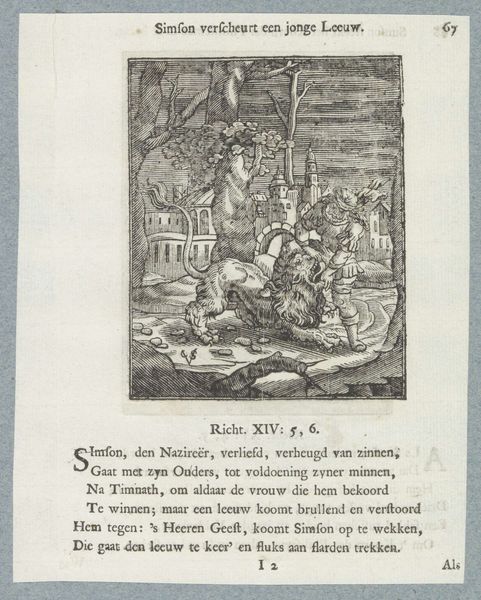

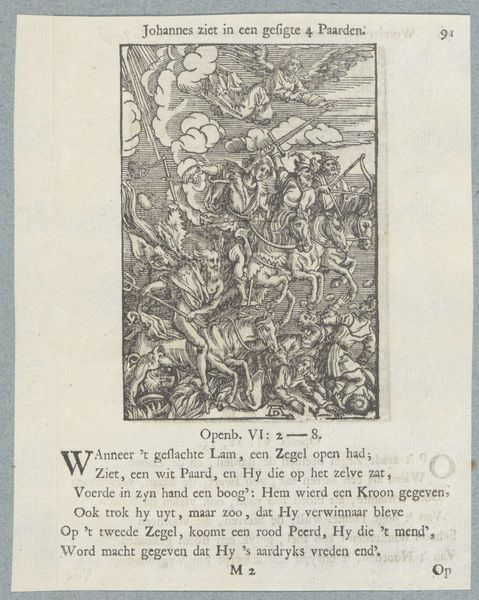

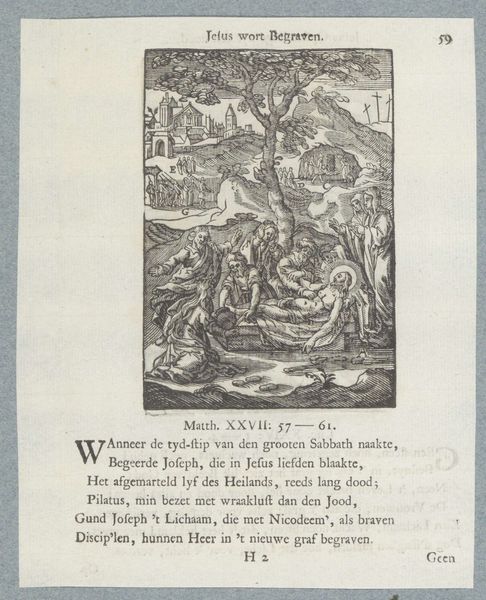

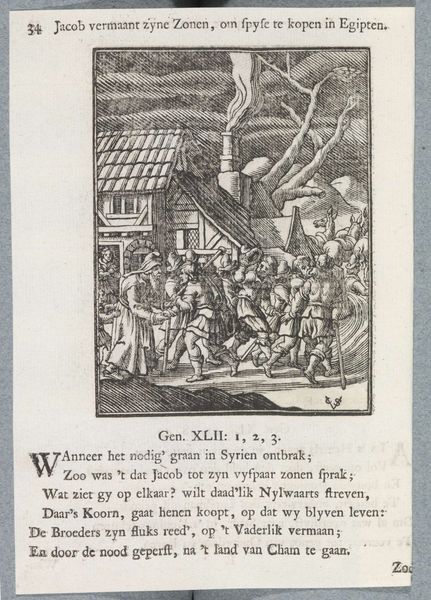

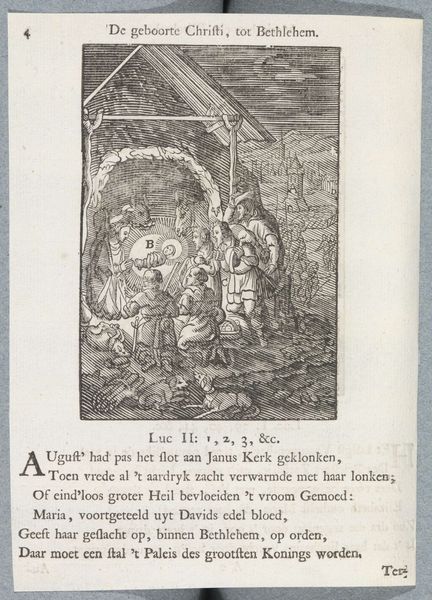

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

traditional media

#

figuration

#

personal sketchbook

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 105 mm, width 86 mm, height 169 mm, width 125 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Right, here we have "The Reconciliation of Jacob and Esau." It’s an engraving, placing it somewhere between 1645 and 1740. It’s currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Immediately, I’m struck by the stark contrast—all these tightly packed figures. It's like a drama unfolding in layers, a bit claustrophobic, isn't it? The detail crammed into such a small space gives it an intense, almost dreamlike quality. Curator: Precisely. It’s from the hand of Christoffel van Sichem II. He worked extensively with woodcuts and engravings, popularizing biblical scenes for wider audiences. Note the biblical text beneath the illustration. Editor: It's fascinating how visual storytelling was intrinsically linked to written word in disseminating ideology. Seeing Esau embrace Jacob, with all his armed men in tow... I can’t help but view this image as a powerful statement on forgiveness after a conflict driven by familial tensions, inheritance, and even deceit. Curator: It speaks to something deeply human, doesn't it? The image captures this profound, perhaps uneasy truce. The Baroque style really leans into the emotional weight. Editor: And who benefits from that "reconciliation"? Is this really about forgiveness, or the preservation of power? The armed figures framing Jacob, while Jacob kneels, emphasizes how social hierarchy intersects the personal, reinforcing dominant patriarchal structures of the time. Curator: Yes, but let’s consider Jacob’s family over on the left, the delicate shading there creates such an innocent softness. A vulnerable group hoping for the best, you know? They represent what is at stake and a potential fresh start. Editor: I recognize the family unit as vulnerable. I wonder whether viewers from a long time ago saw this the same way, or viewed women and children simply as assets within patriarchal structure. The narrative is multilayered in terms of religion and politics. The viewer decides how these issues are reconcilable, like the figures in the image. Curator: Right! It reminds us how art—even prints intended for the masses—can be interpreted in such diverse ways. Editor: Precisely. By interrogating the complexities and tensions of a single artwork we can unveil historical narratives about race, gender, and power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.