Dimensions: height 83 mm, width 103 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

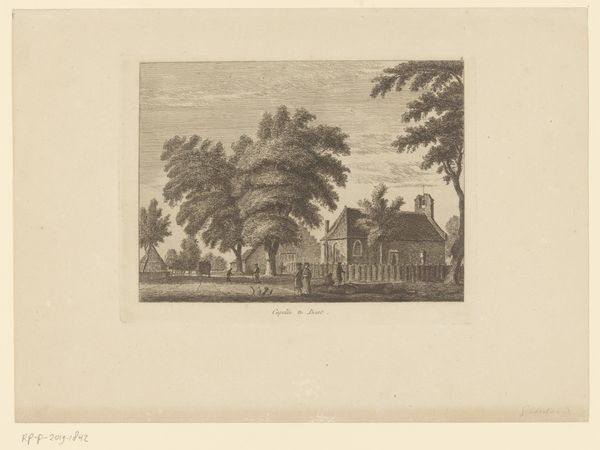

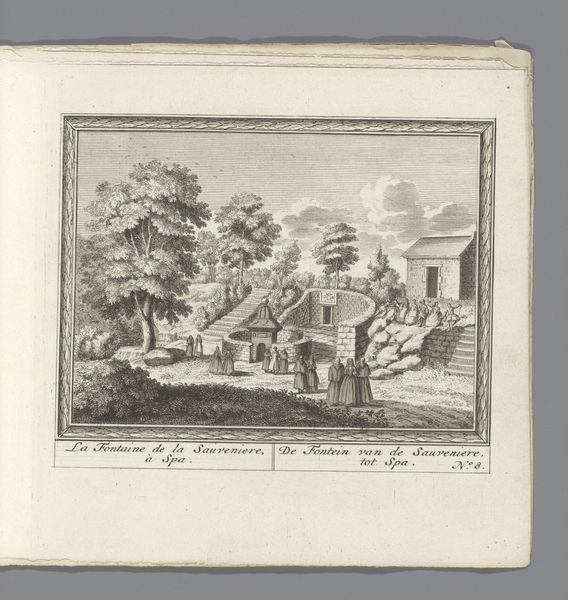

Curator: Here we have Hendrik Spilman’s etching titled, "Gezicht op Kerkwerve, 1745," now residing at the Rijksmuseum, although it was likely created between 1754 and 1792. It depicts the village of Kerkwerve. Editor: There’s such a stark contrast between the busy, textured sky and the quiet village scene below. It almost feels… unsettling. Like nature’s poised to swallow it all. Curator: It's an interesting reading, indeed. Spilman was documenting the Zeeland region of the Netherlands, a province characterized by its constant struggle with the sea, particularly poignant in that era. The image presents, on one hand, a peaceful and rather unremarkable village and a rather foreboding sky that signals to any contemporary viewers of constant concern over their position relative to their landscape. Editor: Yes, I understand now, particularly as I notice the lone figures to the left. There’s an emphasis on everyday life, even the church serving a secular meeting-place function given how people simply gather out front rather than piously enter for mass. How complicit was Spilman with this landscape of everyday Dutch life as subject to constant peril? Curator: The engraving medium lends itself to precisely this feeling. With its minute lines and shading, it builds to a detailed yet somehow distant scene. Editor: I keep coming back to those little figures... and the mounted figure too, like there's some kind of story implied about belonging, surveillance, the gaze of the privileged over ordinary life… Was the landscape something to be managed or an active part of village identity? Curator: Given the date and Spilman's interest, I imagine the print had quite a bit of success amongst locals, even in what were early versions of tourism where Netherlanders would seek prints depicting landscapes as mementos and emblems of pride. I should like to read the letters about and other ephemera regarding prints of landscape to more fully realize how these landscapes of everyday life may be considered also scenes of power. Editor: It certainly complicates the typical associations we often make with 18th-century Dutch landscape paintings, typically rendered as a reflection of some form of colonial power elsewhere in the world. I will have to read some studies on landscape and domestic policy. Thanks for this tour through place and the powers invested there. Curator: My pleasure. This exploration shows just how much history a seemingly simple etching can reveal about its time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.