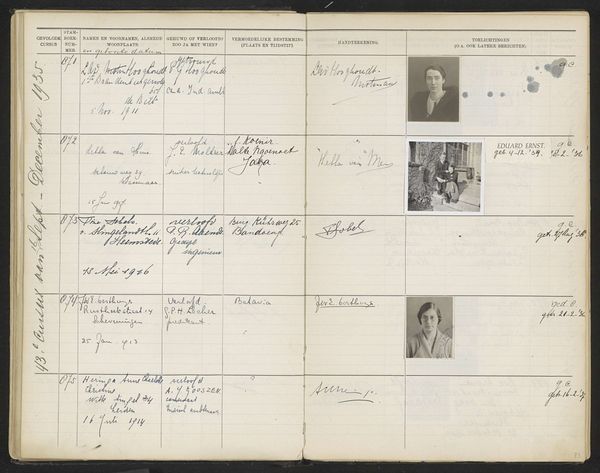

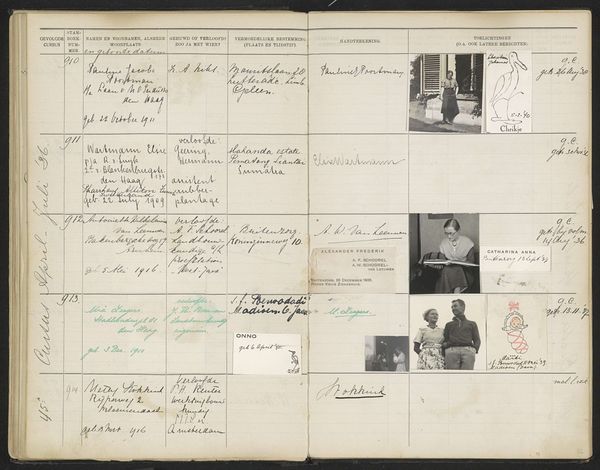

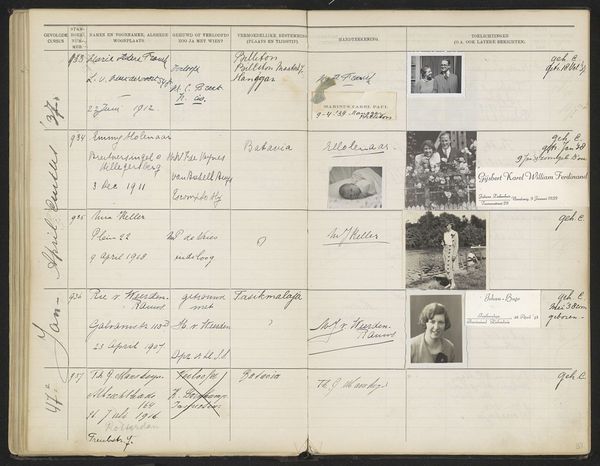

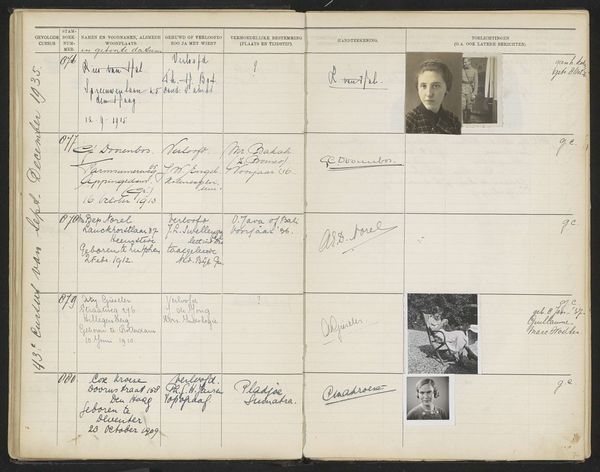

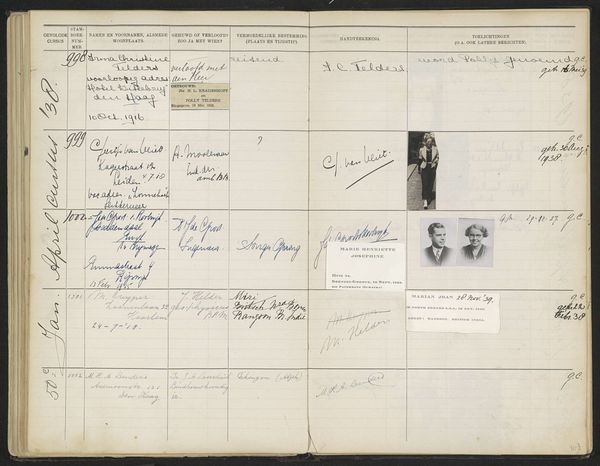

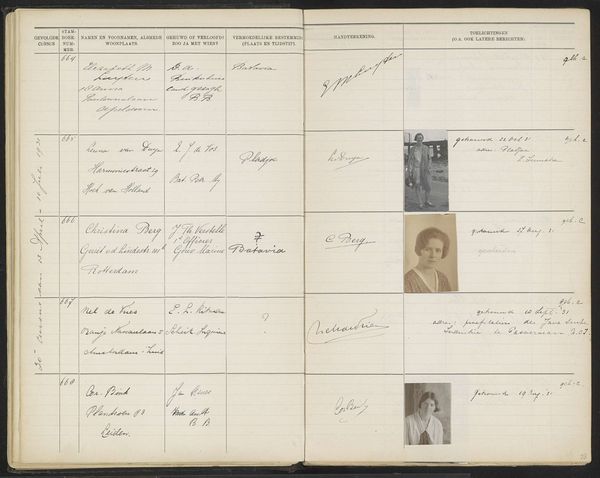

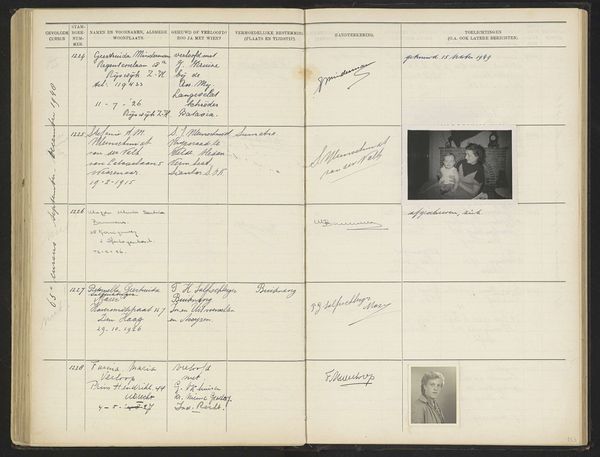

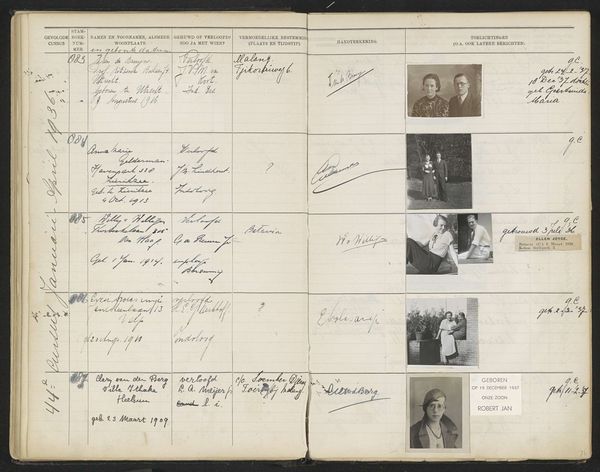

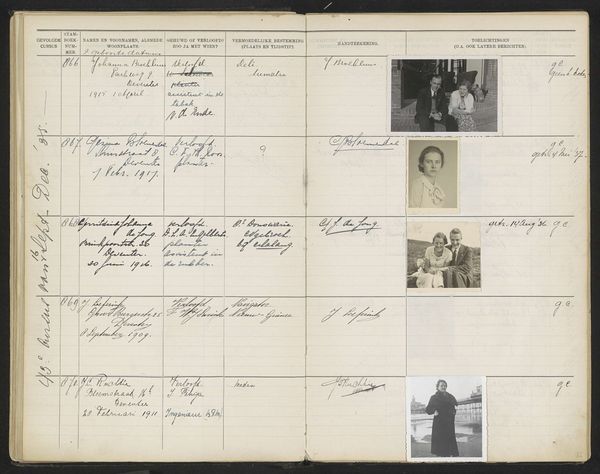

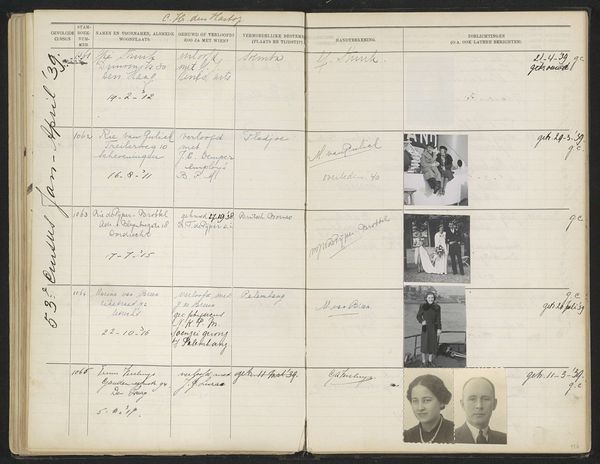

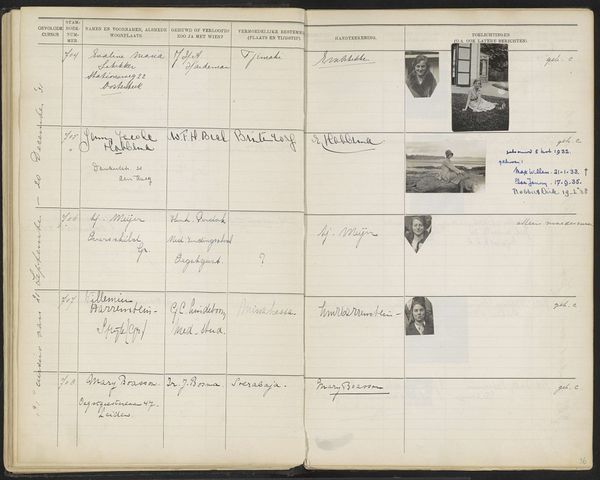

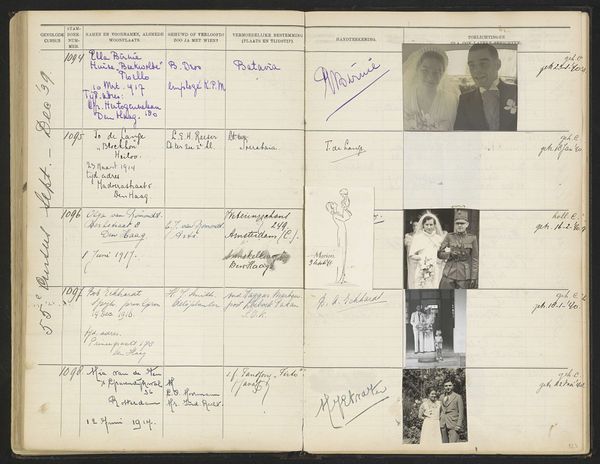

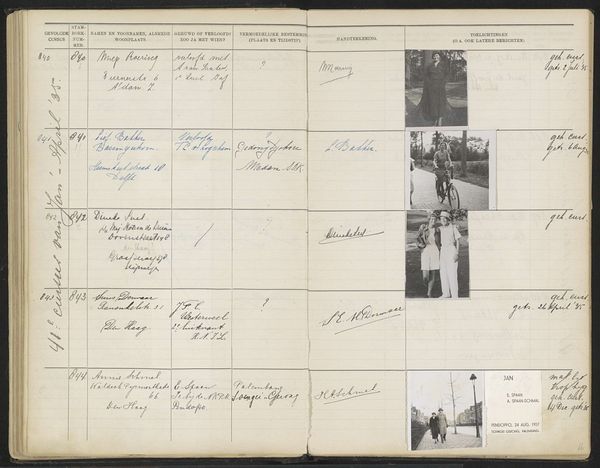

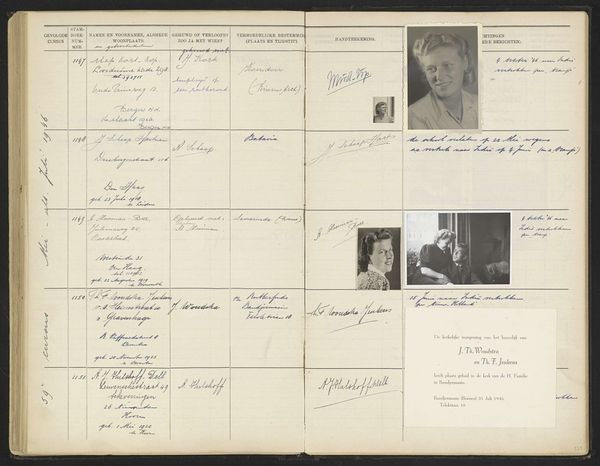

Blad 64 uit Stamboek van de leerlingen der Koloniale School voor Meisjes en Vrouwen te 's-Gravenhage deel II (1930-1949) Possibly 1935

0:00

0:00

drawing, mixed-media, paper, photography

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

aged paper

#

mixed-media

#

hand-lettering

#

dutch-golden-age

#

sketch book

#

hand drawn type

#

paper

#

photography

#

personal sketchbook

#

hand-drawn typeface

#

fading type

#

sketchbook drawing

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

sketchbook art

Dimensions: height 337 mm, width 435 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have "Blad 64 uit Stamboek van de leerlingen der Koloniale School voor Meisjes en Vrouwen te 's-Gravenhage deel II (1930-1949)", possibly from 1935. It's a page from what appears to be a student registry, with photographs and handwritten entries. I'm struck by how personal and yet institutional it feels. How would you interpret a piece like this? Art Historian: What immediately catches my eye is the complex interplay between the individual and the colonial project embedded within this “Stamboek”. Who were these girls and women and what role did they play, willing or unwilling, within colonial structures? The handwritten entries alongside photographs tell personal stories but are framed by institutional classification and control. Consider the power dynamics inherent in recording and categorizing these women, particularly within a "Colonial School.” What implications does it raise? Editor: So it's not just a record but also a reflection of colonial power? I guess I was mostly seeing it as a collection of individual stories preserved in time. Art Historian: Exactly. Consider how knowledge itself can be a tool of colonialism. The act of documenting, archiving, and classifying these students – ostensibly for administrative purposes – also reinforces a hierarchy. Who decides what information is important and how it is presented? What perspectives are being erased or amplified through this process? What do the handwritten notes reveal or conceal about their social and ethnic backgrounds? Editor: I never really thought about the political dimension of something seemingly so benign. It definitely makes me see the book page very differently now! Art Historian: It urges us to confront the uncomfortable aspects of history and challenge dominant narratives. Thinking about these young women also illuminates discussions around gender roles and their education, as their access to education would have been very limited compared to their male counterparts. This object acts as a lens through which we might question power structures then, and their resonance now. What lasting impact might the Dutch colonialism have left on those involved and their families? Editor: I’ll be sure to research this period further, as now it is starting to reveal itself as an actual physical document from this world instead of something more innocuous. Thank you for shedding a light on a completely new reading of it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.