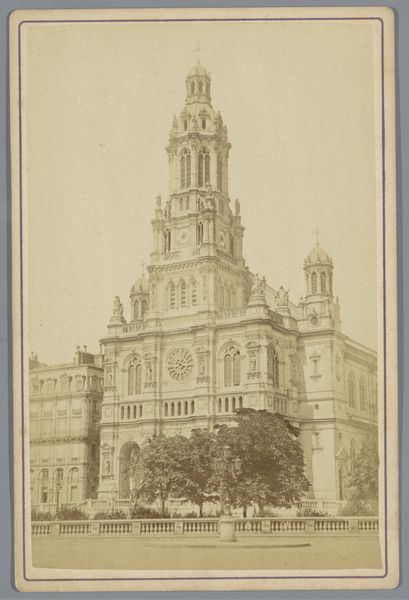

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

cityscape

#

realism

#

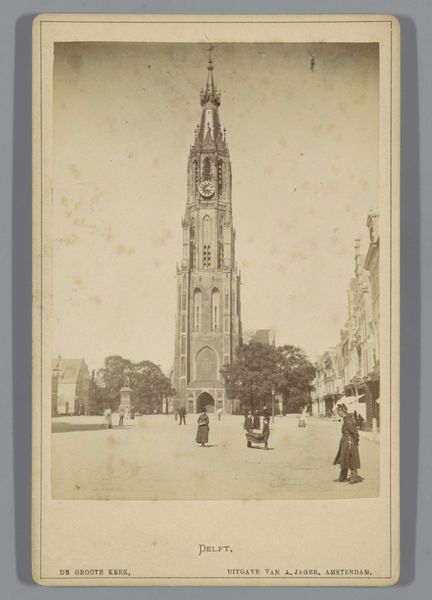

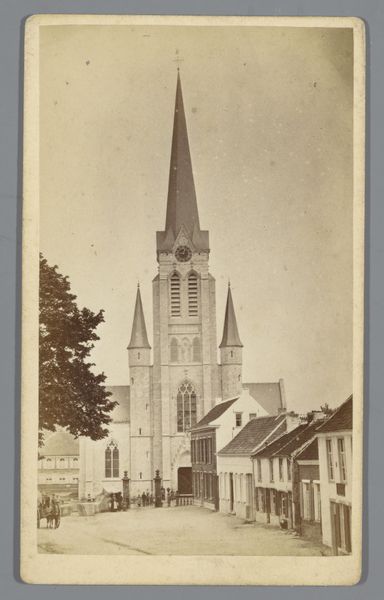

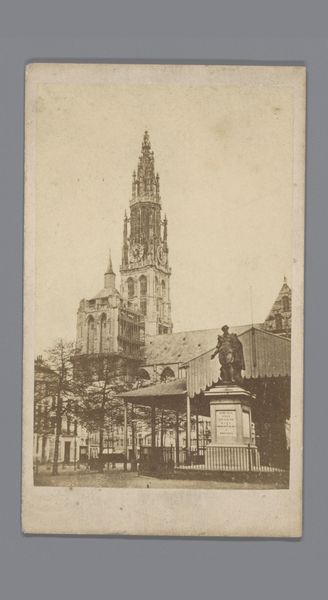

building

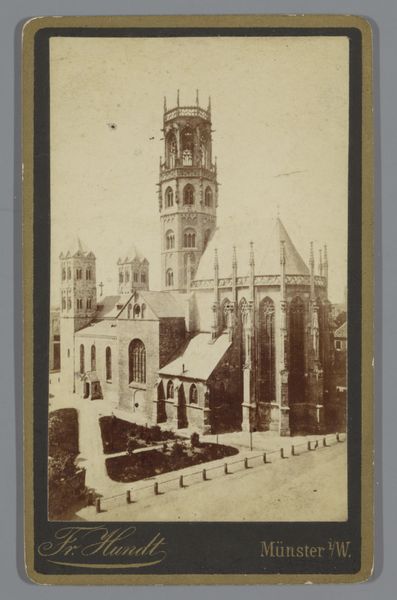

Dimensions: height 167 mm, width 109 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Sophus Williams' gelatin-silver print, "Gezicht op de Jerusalemkirche te Berlin," created in 1880. It's a stately depiction of the church. It makes me wonder about the city's relationship with religious architecture at that time. What do you see in this photograph that speaks to that relationship? Curator: Well, beyond its immediate architectural representation, consider the image as a document embedded within the context of a rapidly changing Berlin. The Jerusalem Church, originally a haven for Bohemian refugees, becomes a symbol of religious tolerance and assimilation in a burgeoning imperial capital. The act of photographing, then reproducing this image, is itself a statement, participating in the construction of a civic identity. Think about who might have commissioned or consumed this image. What social classes, political agendas, or ideological positions might it reflect or reinforce? Editor: That’s fascinating, I hadn’t considered the act of photographing as an endorsement of particular social values. Were there any particular political tensions during the late 19th century that influenced the reception of this photograph? Curator: Absolutely. The *Kulturkampf*, or "culture struggle," a period of anti-Catholic persecution, was still a recent memory. So, depicting a Protestant church – especially one associated with a marginalized community – could be interpreted as a subtle affirmation of the state’s power and a reminder of controlled religious expression. And the emerging medium of photography played a vital role in disseminating such ideologies. Do you notice anything about the people depicted in relation to the architecture? Editor: There's almost nobody there... just a few indistinct figures, like they are deliberately excluded, which almost exaggerates the dominance of the architecture... almost like people aren't even part of the picture. I hadn't considered how the absence of people might itself send a specific message. Thanks, this has been a really helpful recontextualisation. Curator: Indeed! By questioning whose stories are centered and whose are marginalized, we gain a far richer understanding.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.