drawing, print, pencil

#

drawing

# print

#

pen sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

pencil drawing

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

pencil

#

realism

Dimensions: Image: 304 x 406 mm Sheet: 405 x 582 mm

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

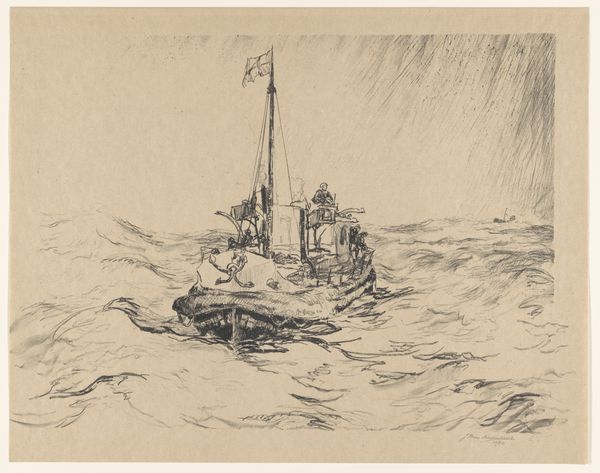

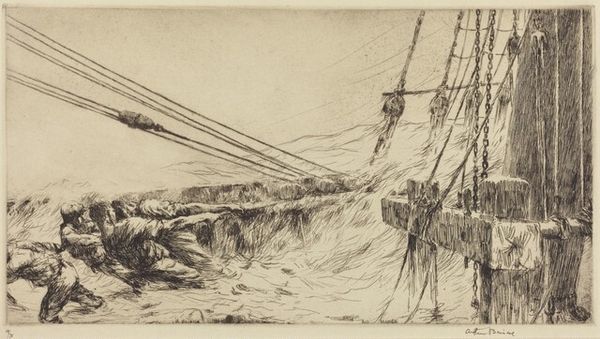

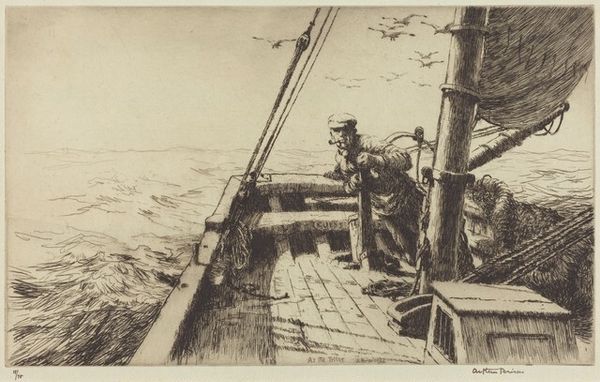

Curator: This print, titled "Surf Casters," was created by Dayton Brandfield sometime between 1935 and 1939 using pencil and other drawing media. Editor: It’s a compelling scene—sort of bleak and powerful. The figures battling the surf…there’s an almost heroic feel, despite the understated medium. It brings to mind issues of labor and leisure amidst the social realities of the time. Curator: I agree, the scene depicts more than leisure; it underscores the physical act of labor, evident in the positioning of the figures in contrast to the overwhelming ocean waves. This print makes me curious about Brandfield’s own connection to manual work and the production processes evident within the composition, which he chose to render using pencil techniques, highlighting accessible and cost-effective methods, resonating with economic realities. Editor: Precisely! And given the period, we cannot ignore the backdrop of the Great Depression. These weren't just guys relaxing; it’s possible that fishing was supplementing their diets or even providing an income. There’s a raw, unvarnished quality that hints at class and economic struggle. Who were these men? What were their lives like beyond this snapshot? Also, the use of realism invites a critical look at the depiction of the male form. Is it idealized, or does it attempt to reflect the everyday realities of working-class bodies? Curator: Absolutely. Looking closely, you notice Brandfield focused considerable attention on capturing the play of light across the water. The artist masterfully used various drawing techniques to add textures which give life to the water currents and the figures struggling against them, while the subtle use of pencils seems appropriate with Brandfield's choice of material speaking to broader implications around resourcefulness and constraints within creative practice during this era. Editor: This also leads to how accessibility to recreation differs across gender and class lines, as we consider these representations in their social environment. Was Brandfield aiming to make a commentary, or merely capturing his own time, place, and lived experience as honestly as possible? I want to know whose perspectives went unnoticed back then! Curator: Good point! Seeing how his work stimulates such dialogue gives the print a life far exceeding the mere image. Editor: Right! Art becomes meaningful only through conversations that acknowledge not just brushstrokes, but broader societal concerns, don't you think?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.