print, engraving

# print

#

landscape

#

perspective

#

northern-renaissance

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 192 mm, width 245 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

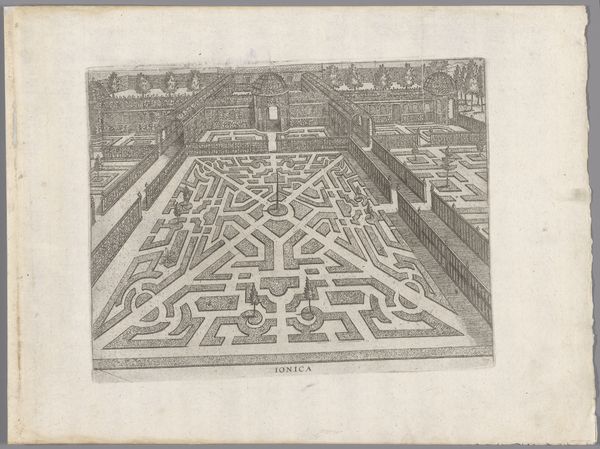

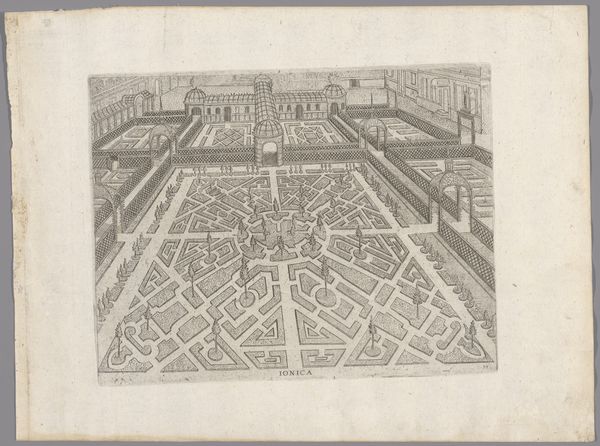

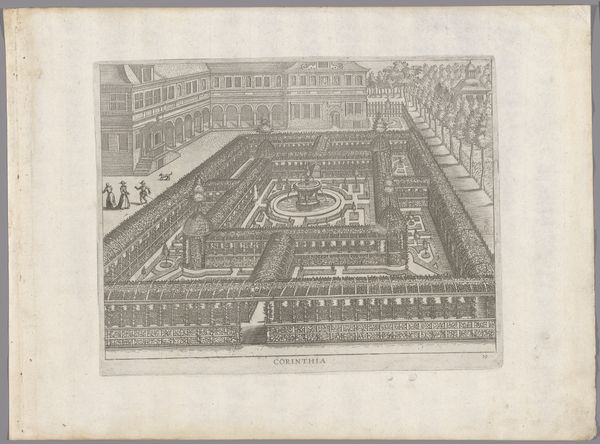

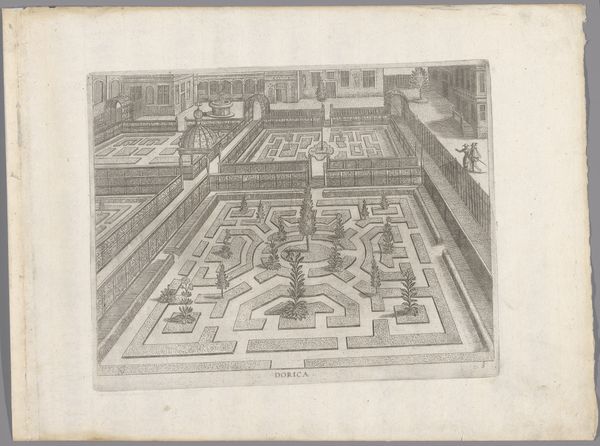

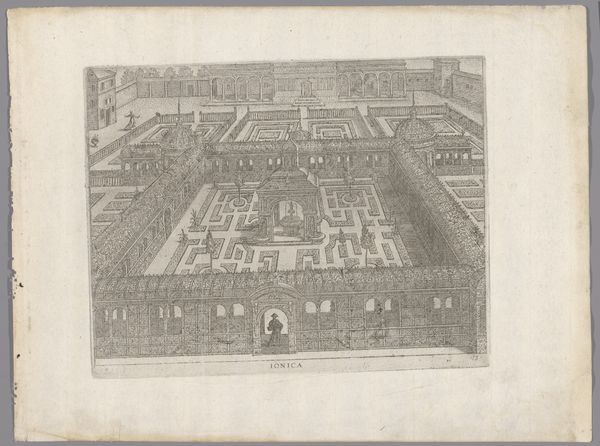

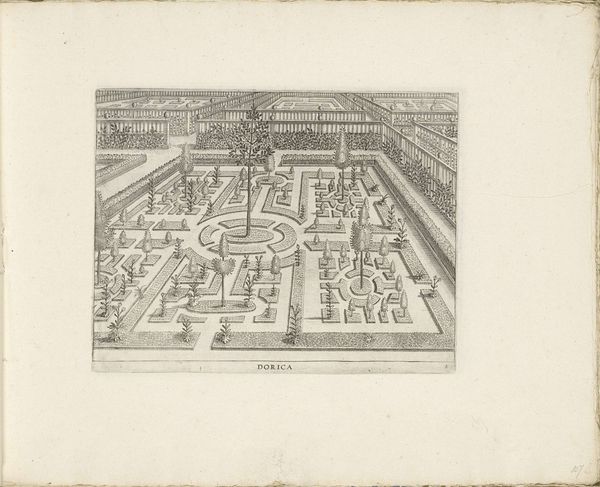

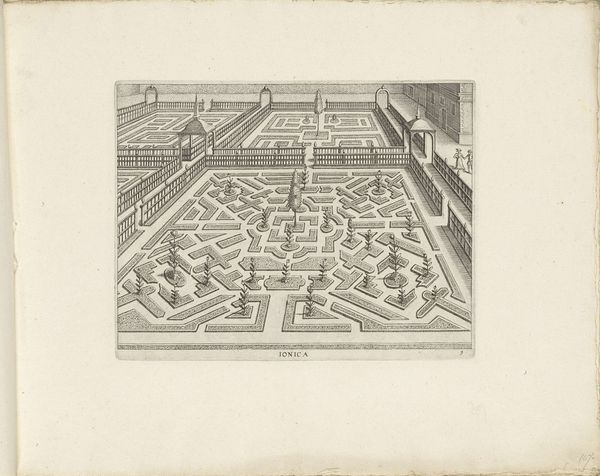

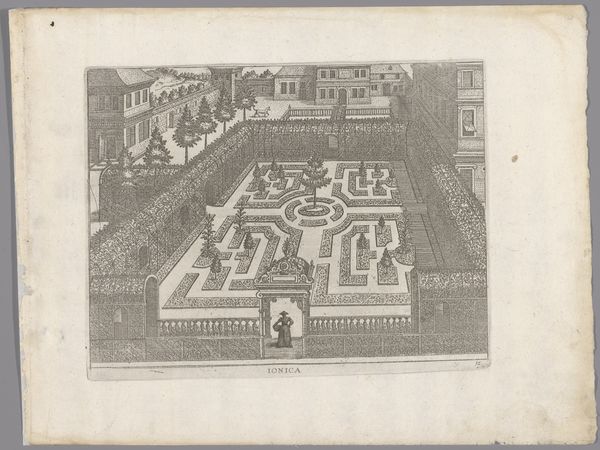

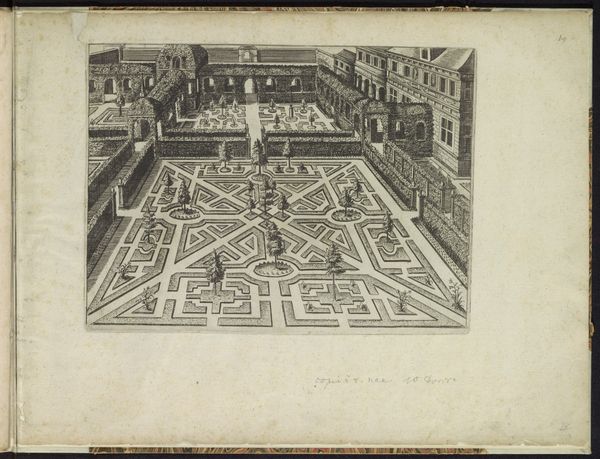

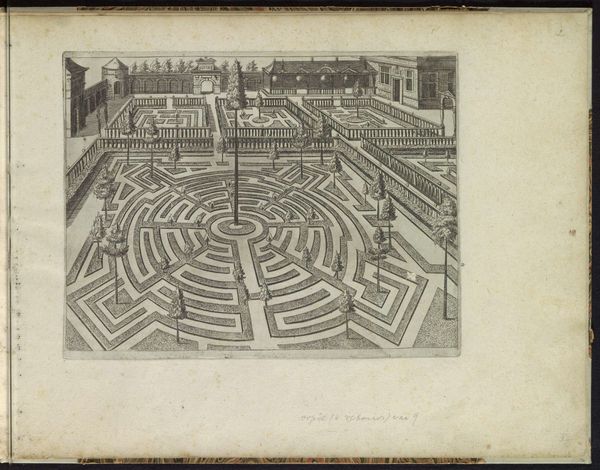

Curator: Here we have a print entitled "Tuin met een parterre met in de hoeken fleurs de lis" dating back to 1583. It's an engraving currently held at the Rijksmuseum and believed to be by an anonymous artist. Editor: My initial impression is one of rigid control, even claustrophobia. The density of lines really emphasizes that geometric structure. Curator: Yes, the meticulous lines of the engraving medium lend themselves perfectly to capturing the structured precision that defines this garden's layout. Consider the semiotic weight of the fleur-de-lis in the corners – symbols of French royalty placed within such a deliberately designed space. It signifies power, order, and the imposition of human will onto nature. Editor: I find myself focusing on the sheer labour involved in rendering this space. It wasn't merely drawn but built, shaped with tremendous manual effort. Someone physically had to create those precise parterres, prune the hedges... the human element seems somewhat erased in the final image. Curator: And yet, is not this eradication of visible human toil itself a formal device? The artist isn't just rendering a garden, but also a concept – the power and privilege required to erase all visible trace of making, crafting such space through others work. The very act of creating this highly mannered space and capturing in an engraving embodies artistic refinement. Editor: So the labor becomes almost allegorical. An absence that speaks volumes about the society from which this image sprung? Curator: Precisely. Look at the formal use of perspective and symmetry, both central tenets of Renaissance aesthetic principles. The entire composition is engineered to create an illusion of depth and control – projecting the ideals of harmony and proportion. Editor: Yes, but those principles are brought into question when considering how that labour affected the landscape itself and the people who worked upon it. Was this aesthetic truly harmonious for all involved or only the select few who enjoyed such cultivated artifice? Curator: It's a potent point. This work serves as both a window into a historical moment, and a lens through which to consider ongoing power structures encoded in spatial and aesthetic forms. Editor: Seeing the interplay of labor and landscape here has made me question whose narratives get etched, quite literally, into these images and preserved by establishments like this museum.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.