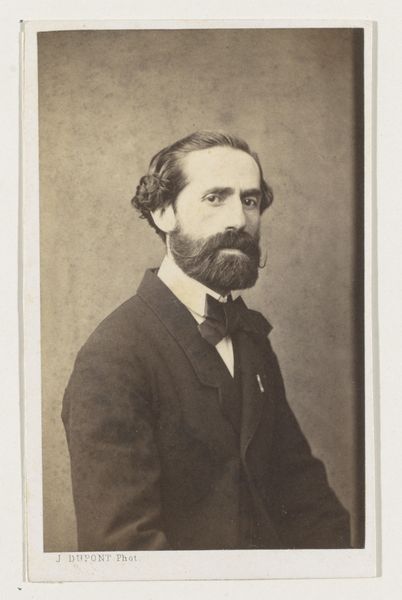

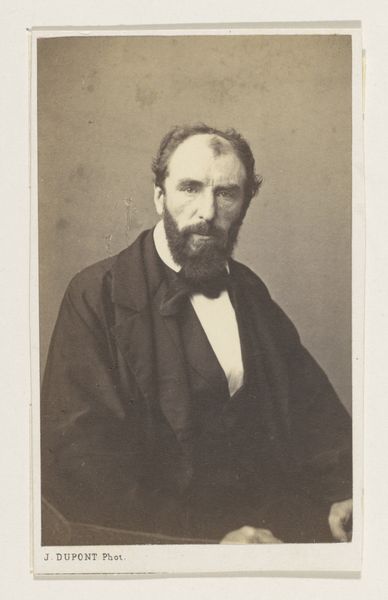

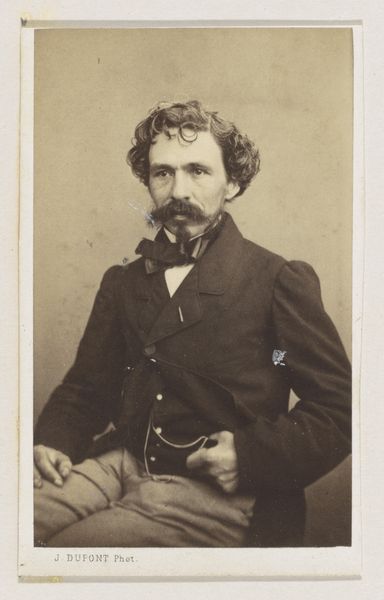

daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

realism

Dimensions: height 100 mm, width 62 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

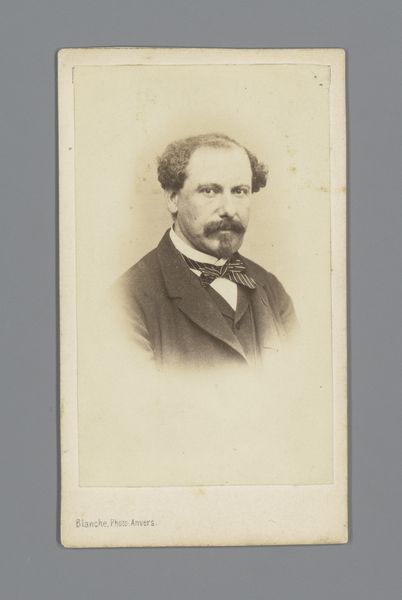

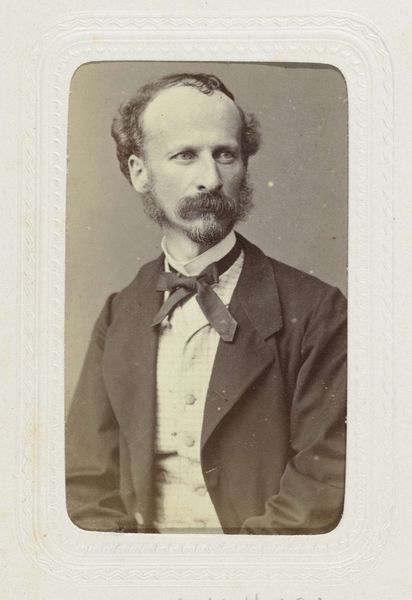

Curator: Let’s turn our attention to this arresting daguerreotype by Joseph Dupont, titled "Portret van de beeldhouwer Jacques De Braekeleer, halffiguur," dating from 1861. Editor: He certainly has a striking gaze. It feels both intense and a little melancholic, doesn't it? There's also something about the starkness of the photographic process here. Everything is so defined. You really get a sense of the materiality of the era through it. Curator: Absolutely. Dupont captured De Braekeleer, a sculptor, in a way that feels very modern even now. Note how the light catches the planes of his face. And the beard. That’s an obvious signifier, almost announcing, “Here is a man of substance, a man of art.” Editor: Speaking of substance, think about the technical demands! Each daguerreotype was a unique, meticulously crafted object. Coating a silvered copper plate, exposing it in the camera, developing it with mercury fumes – it’s a hazardous and alchemical process. This image is as much about the skill of Dupont, the photographer, as it is about the sitter, De Braekeleer, the sculptor. Curator: Indeed. The very act of creating a photographic likeness had ritualistic significance. And for someone like De Braekeleer, whose profession involves the tangible manipulation of matter, there’s an interesting visual mirroring at play. Consider also the fact that this daguerreotype allows a more direct connection, almost a glimpse into the mid-19th century sensibility. The symbolic importance can’t be ignored. Editor: And while De Braekeleer likely pondered how he'd be remembered, Dupont, in mastering such a technical and physically demanding medium, also aimed for a kind of immortality, leaving a material trace. It begs the question: which man leaves behind a more lasting legacy through his work? The man shaping matter, or the one capturing light? Curator: A compelling point. It adds another layer to our interpretation. We started seeing this image simply as a record of a moment. And it ends with it being an insight on creation itself. Editor: I agree. This daguerreotype makes me appreciate both the technical rigor of early photography and the artist’s unwavering gaze.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.