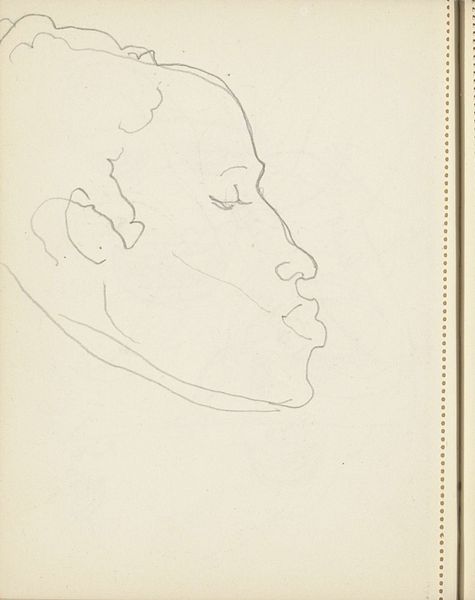

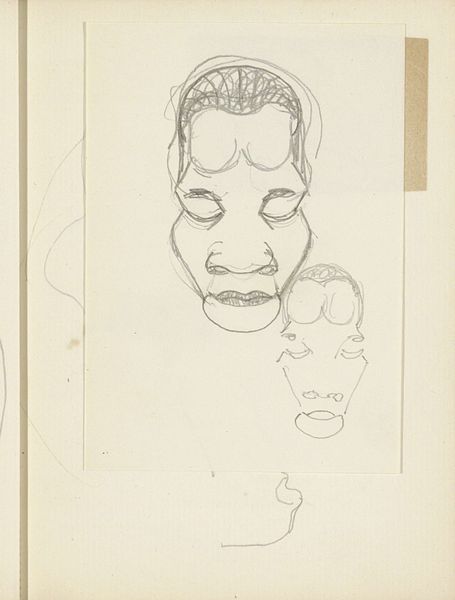

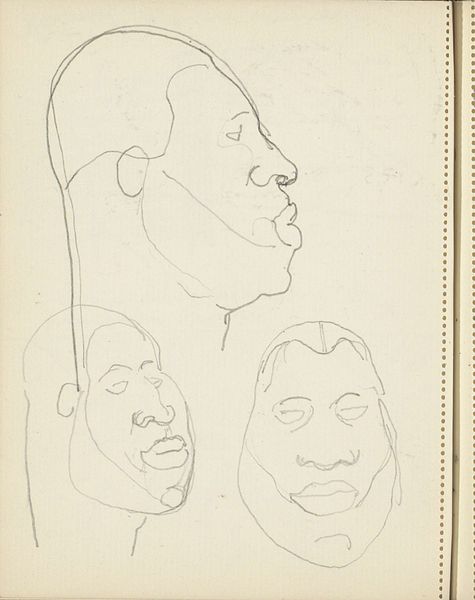

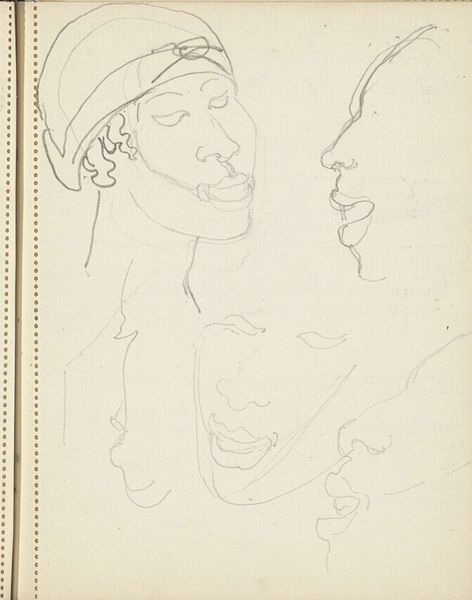

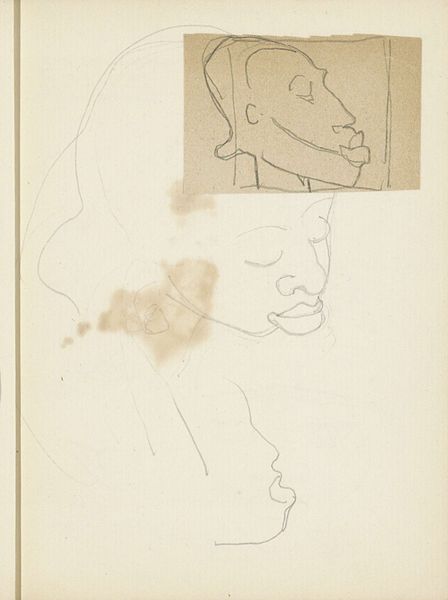

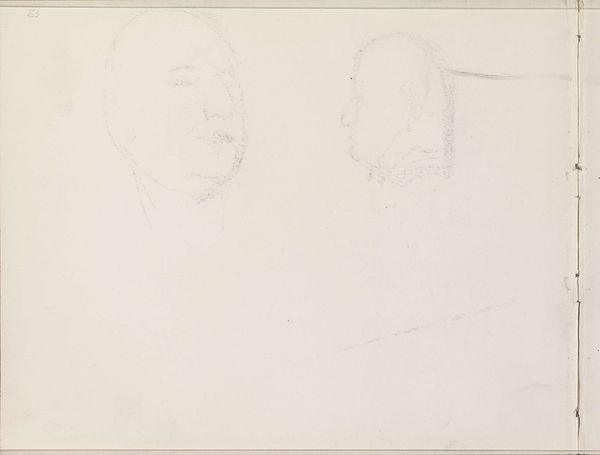

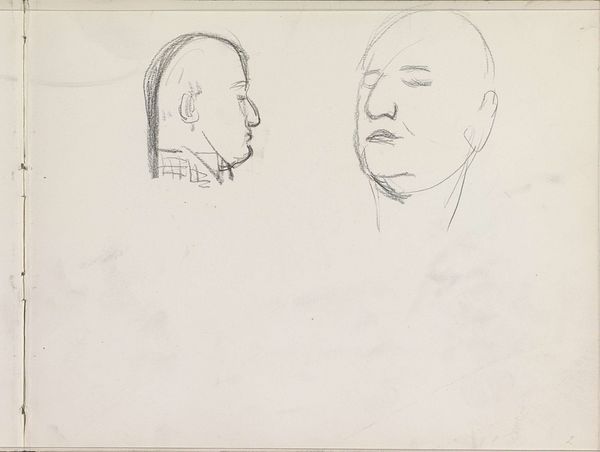

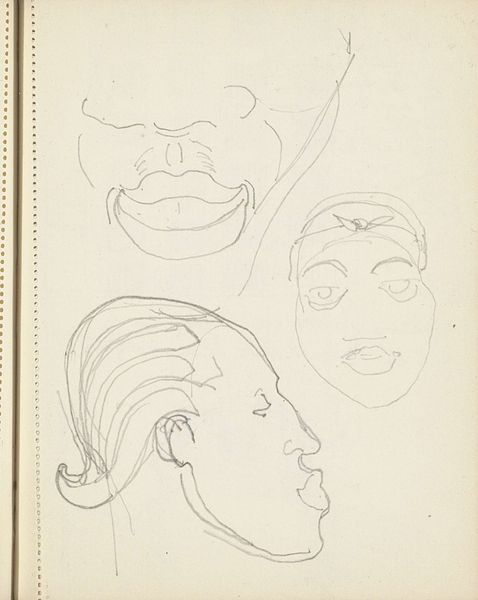

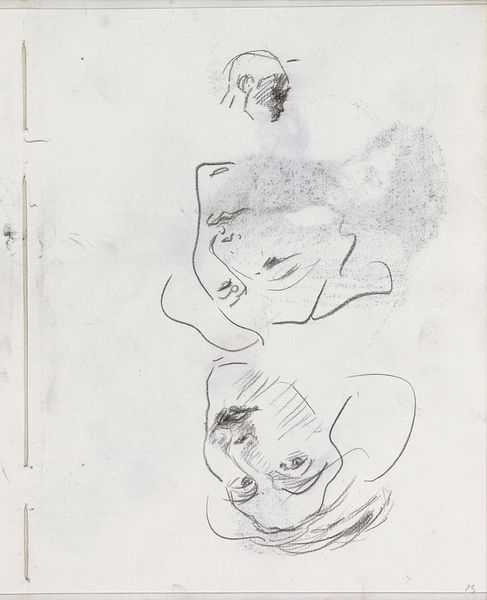

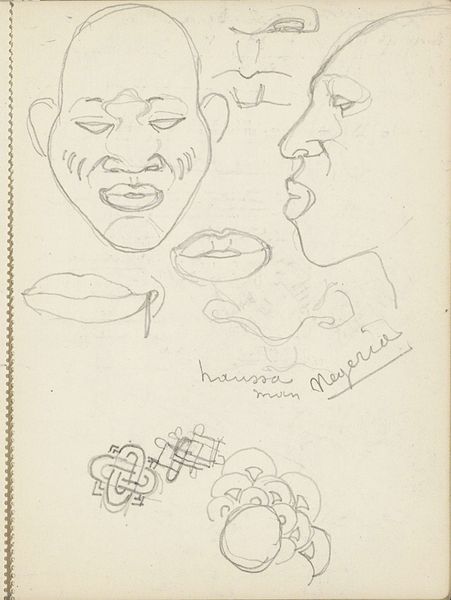

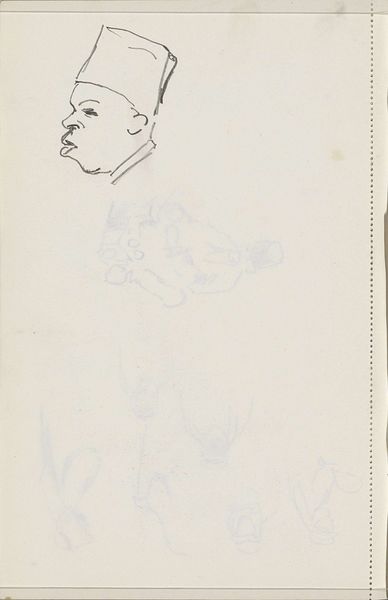

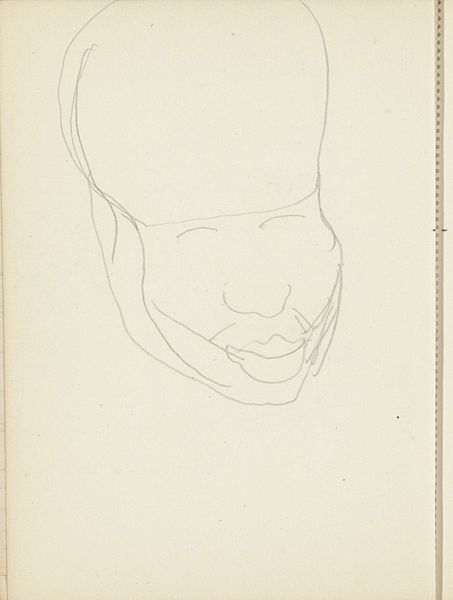

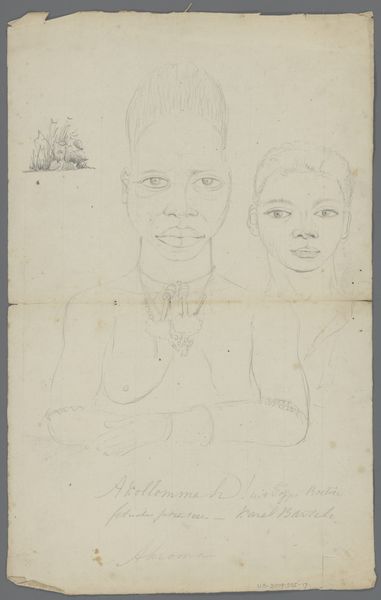

drawing, pencil, graphite

#

portrait

#

african-art

#

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

pencil

#

line

#

graphite

#

portrait drawing

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What strikes me first is how raw and vulnerable these figures appear. Is that your impression as well? Editor: It is. There’s an immediacy, a kind of directness that is hard to ignore. I wonder, though, how that vulnerability plays into the broader historical context. This work, “Hoofden van Afrikanen,” or “Heads of Africans,” dates roughly from 1916 to 1945, and is currently held in the Rijksmuseum collection. Considering the historical and social climate of that period, these pencil and graphite sketches feel…complicated. Curator: Complicated in what way? Editor: Well, the sketch captures the subjects using quick strokes. It feels intimate, but is that intimacy authentic or exploitative given the power dynamics inherent in representation, especially representation of African people by a likely European artist during that era? I'm curious how the original audience might have perceived these images, and how their reception might differ today. Curator: It's a valid and vital point. The simplicity of the line work allows us to project onto these faces, doesn’t it? There is the risk of imposing contemporary readings but to deny this social history, the symbolic weight of the racialized gaze is to deny the work itself its emotional truth, its complex story. Editor: Exactly! These aren't just aesthetic studies, they're documents, reflecting the artist's perceptions, the culture that shaped those perceptions, and our own ongoing struggles to come to terms with that legacy. So what do you find significant from an iconographic perspective in this portraiture work? Curator: In some ways, it reflects back our own incompleteness in our visual narratives. This image acts almost like a mirror. If we focus solely on what is visibly depicted within it, or technically rendered by its creator, we'd probably fall short in gaining something insightful. In particular, this example can tell us about colonial art practices through the seemingly "simple" act of sketching faces of African peoples with so-called 'Africain' methods. Editor: A sketch like this raises critical questions about representation and reception and who controls those visual narratives. Ultimately, isn’t art at its best when it challenges us to confront difficult histories? Curator: Agreed. It's a visual fragment, pregnant with meaning and the possibility of understanding, though perhaps never complete. Editor: An apt reflection on this piece indeed!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.