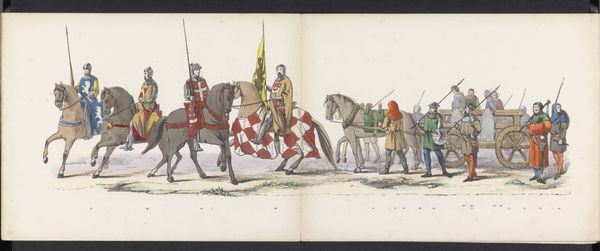

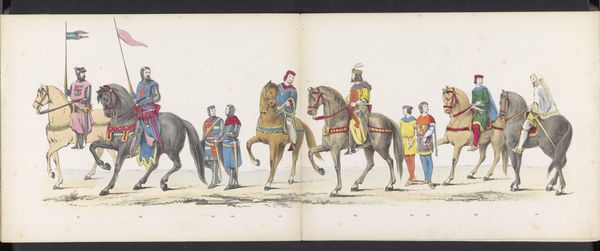

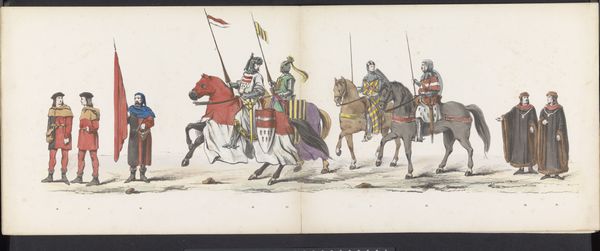

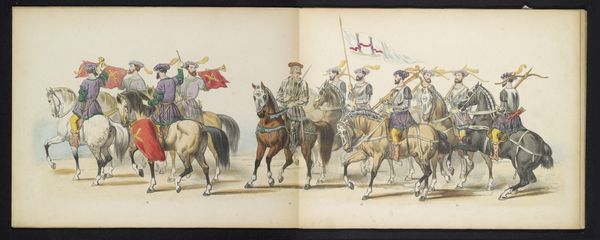

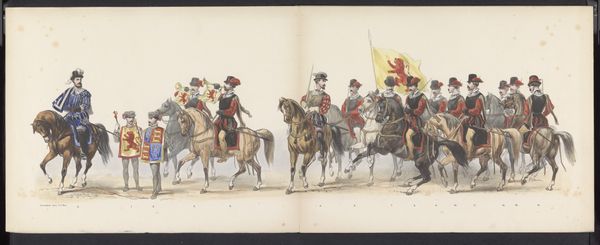

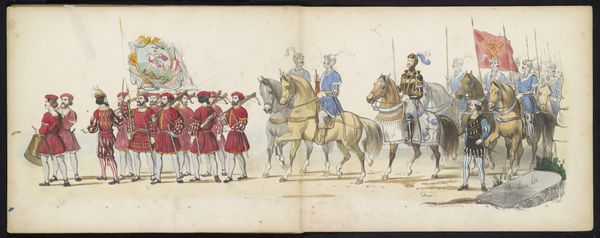

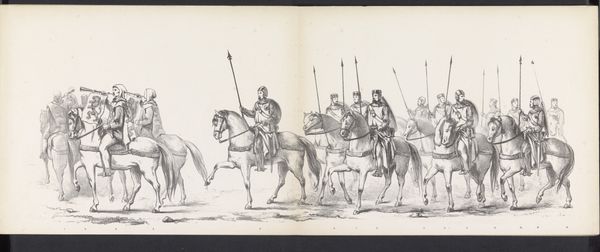

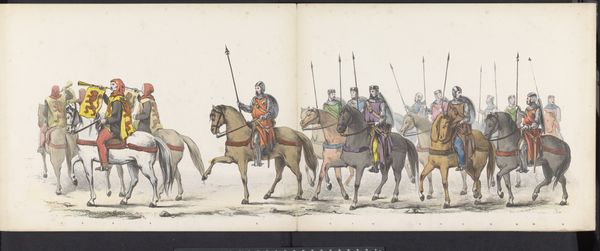

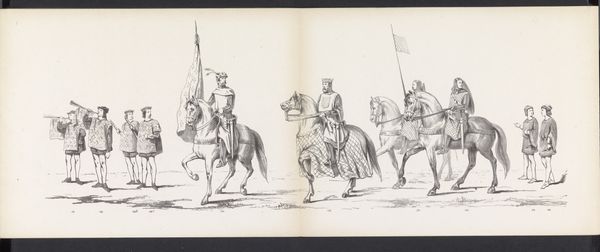

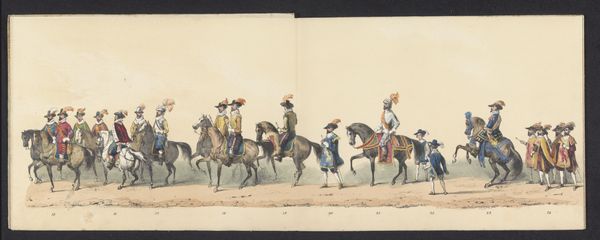

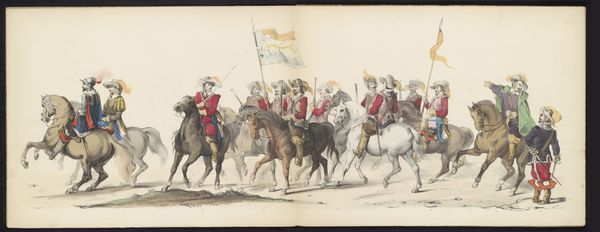

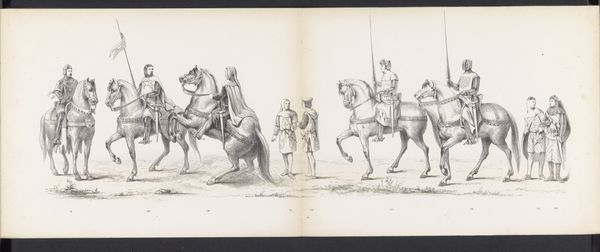

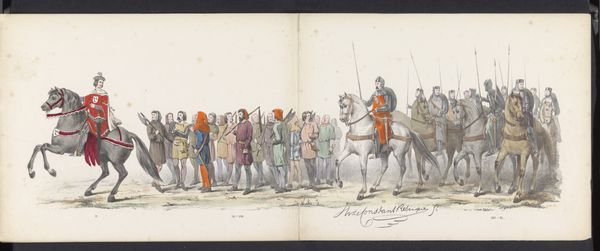

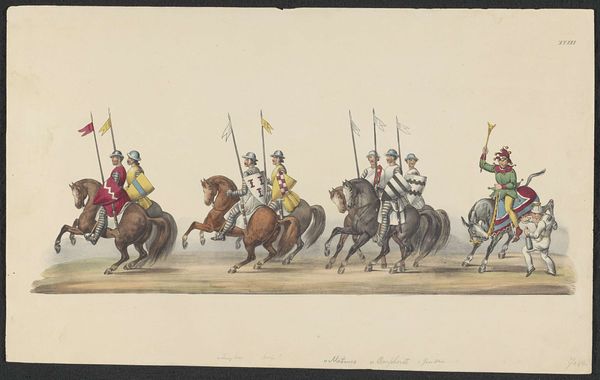

Maskerade van de Leidse studenten, 1865 (plaat 5) 1865

0:00

0:00

print, etching

#

narrative-art

# print

#

etching

#

figuration

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 275 mm, width 720 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Oh, I find this quite striking. It’s “Maskerade van de Leidse studenten, 1865 (plaat 5)” by Jan Daniël Cornelis Carel Willem baron de Constant Rebecque, made in 1865. It’s an etching printed on paper. Editor: My first thought? This reminds me of something out of Monty Python. The procession, the outfits…are they supposed to be, what, crusaders on horseback? It has this quirky theatrical feel, like a history lesson gone wonderfully, gloriously absurd. Curator: Exactly! There’s a subtle playfulness there. De Constant Rebecque seems to have captured this scene with precision; the cross symbols leap off the figures, but the overall palette is muted. This helps underscore its historicist but deliberately artifical context. Look closely; notice the postures of the riders – some upright, some slouched – it almost captures the very *human* side of a supposed medieval crusade. Editor: Oh, it’s all deliberate! Note how he’s chosen the etching medium. It’s almost monochrome and slightly smudgy aesthetic, enhancing the impression of something ancient. However, that splash of faded reds in those crosses stops it from being just dull imitation. He wanted you to question what’s historical re-enactment and what’s, well, utterly tongue-in-cheek. Curator: I think you're spot-on with that observation about the use of colour; the smudging and that limited palette directs your gaze specifically to the titular parade elements and gives it all this curious feel that everything is a deliberate pose – in every sense! Editor: It begs the question about perspective, doesn’t it? Are we laughing *at* the historical LARPers here, or are we meant to find something strangely noble, even tragic, in these student costumes? Either way, it’s delightfully unsettling, and, yeah, makes you want to grab a stuffed parrot and join in the absurdity. Curator: Right. There’s an open quality to the whole endeavour. The piece isn’t interested in making bold or obvious statements. It captures a slice of lived pageantry but doesn’t comment on its socio-historic weight. So very unlike Romantic paintings, which it would share much time with, or later Impressionism which aimed to seize a very momentary mood with similar tools. Editor: Perhaps that’s what truly enthralls me: this etching feels very present, captured, and self-aware about its position between then and now. What a delightful reminder that historical reenactment has never been just history. Curator: Yes, something profoundly and enduringly true in all its absurdity.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.